March 2024

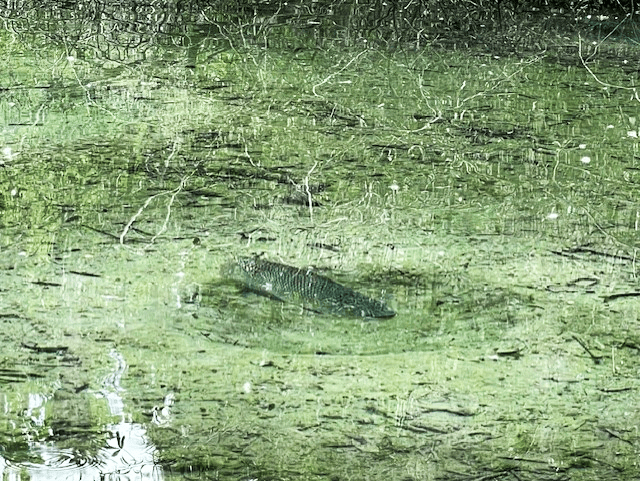

The Alafia River upstream of Lithia Springs. I have many photos of the river that look like paintings.

The Alafia River in this reach felt like old natural Florida.

This project was a lesson in expectations. I did not expect the Weeki Wachee run to be as pretty as it was and I did not expect the Alafia River to be sublimely lovely either.

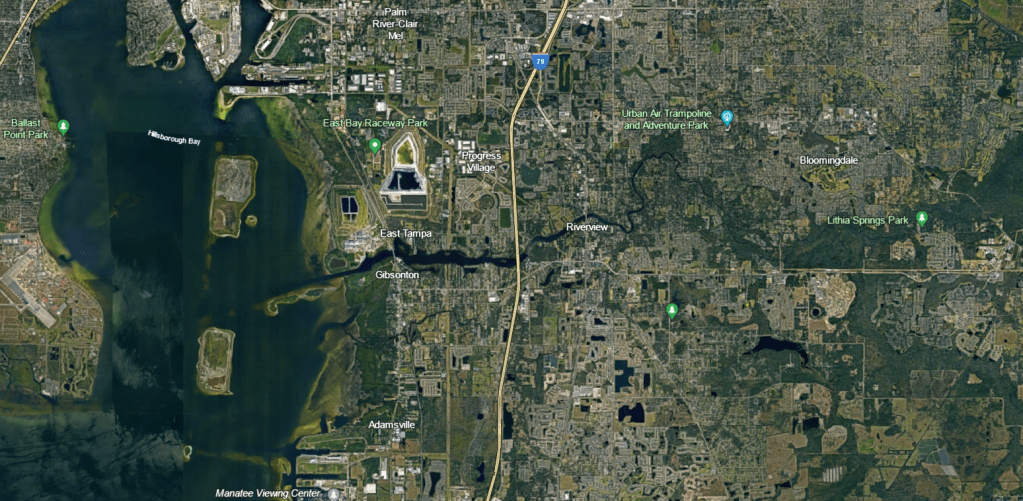

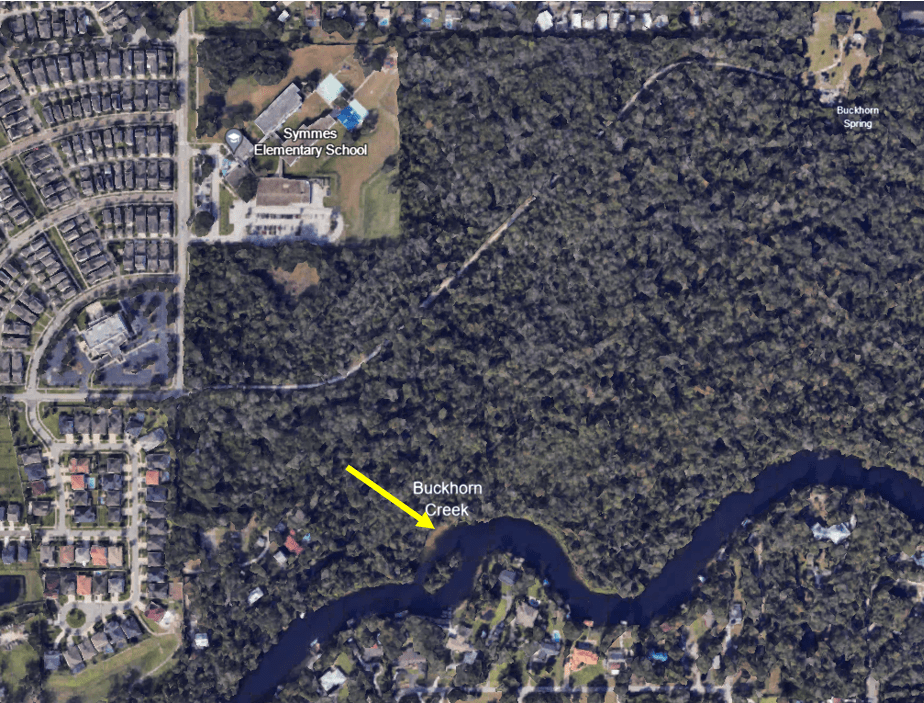

My only experience with Tampa area springs was from the heavily modified springs of the Hillsborough River and my only knowledge about the Alafia came from a paper on the effect of mine drainage and agriculture on invertebrate assemblages. Google Earth images of the landscape around the Alafia River, highly modified with residential development to the west and agriculture to the east, also helped to set my expectations. However, happily, the riparian forest has been preserved in the upper reaches. As a result, the experience of paddling near Lithia and Buckhorn springs feels very natural (as can be seen in the photo above). It just goes to show that you should not listen to your expectations (even those you do not realize that you have).

Google Earth image of the Alafia River, which flows into HIllsborough Bay. Note the green riparian (river) forest along the banks in the upper reaches on the right side of the image.

A lower elevation view of Lithia Major (the big blue pool) and Lithia Minor (the camera icon) as well as the Alafia River.

Lithia Major

Contrary to the natural state of the Alafia in this area, the headspring of Lithia Major was converted into a large swimming pool. However, the park was nice and I appreciated the people spending the day outdoors. Once the spring water leaves the pool, it flows down a short, shallow run into the Alafia River. Lithia Minor is just upstream of Lithia Major.

The Lithia Major headspring was fenced in and closed until the afternoon when the visitors descended upon the pool. Many families were making an afternoon of it.

The canoe launch at Lithia Springs park is a little downstream of the springs, so the short paddle on the river provided a nice alternative to the pool. It was very easy to spot the Lithia Major run, which I came upon first, by the clear plume of spring water flowing into the brown water of the river.

The water of the spring was clear as a bell as it flowed into the tannic, tea-colored river. An exotic armored catfish (Pterygoplicthys sp.) set the stage for what I would see as I paddled up the run.

The rope designated that the run was off-limits to the public and someone from the park raced down to ask me what I was doing when they spied me in my boat. Clearly, they have a lot of pressure from the public, but they were very gracious when I told them what I was doing.

The run was very shallow, sandy, and chock full of exotic fish. After the armored catfish, I next noticed the abundant blue tilapia (Oreochromis aureus) nests.

A very obvious blue tilapia nest.

Three tilapia nests, one with the male guarding it (top), and a closeup of the fish on the nest (bottom).

It was an interesting visit, if slightly shocking, because I have never seen abundances of exotic fish like I saw in the Tampa area springs. Had I spent time observing fish around the canals of south Florida, perhaps I would have been more prepared for the overwhelming biomass of exotic fish in both the Hillsborough and Alafia springs.

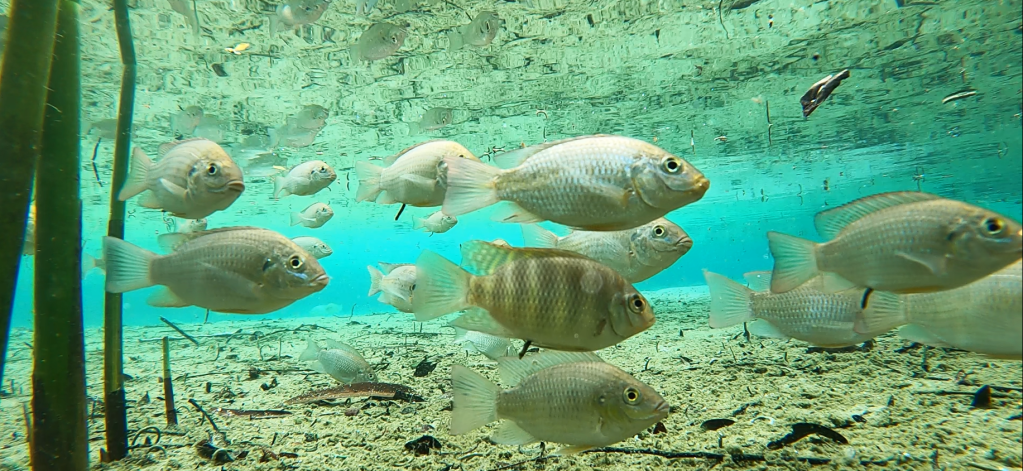

Every fish in these two images from Lithia Major, one from either side of the run, was either a juvenile blackchin tilapia (Sarotherodon melanotheron) or spotted tilapia (Pelmatolapia mariae). While I chose stills from the videos that I thought highlighted the fish well, the videos were filled with these fish. The other videos that I collected from this spring were similar.

The blue tilapia, which were less abundant than the blackchins or the spotted tilapia, dwarfed the other cichlid species. Until I surveyed at Lithia, I had not appreciated how aggressive the blue tilapia could be or how deep their nests were. Blue tilapia build and maintain their nests by picking up sand in the nest site and spitting it outside of the nest.

A blue tilapia building a nest.

I also picked up on video a bunch of the much smaller chanchita (Cichlasoma dimerus, yet another exotic cichlid), The video depicts an interesting feeding behavior of a chanchita in the foreground as it wiggles its tail to kick up food. An aggressive blue tilapia in the background sinks into its nest like a giant hovercraft (a longer version of this video showed the tilapia chasing away fish that approached its nest).

A chanchita doing a little feeding dance while a blue tilapia returns after defending its nest in the background.

Loads of armored catfish littered the run as well.

Armored catfish feeding in the run with a few blackchin tilapia in the background.

I did see a few native fish in the run, mostly seminole killifish (Fundulus seminolis), but also at least one largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and a few individuals of various sunfish species (Lepomis spp.).

Two seminole killifish with blackchin tilapia and armored catfish in the background (top) and a lone largemouth bass with blackchin tilapia in the background (bottom). It is interesting how pale the bass was in this sandy spring.

Lithia Minor

As might be expected, Lithia Minor was a much smaller spring than Lithia Major, with a round and rocky headspring and short, shallow run. The substrate was darker and supported a lot more aquatic plants.

The Lithia Minor run looking out toward the river.

The Lithia Minor headspring and vent (the bluish color).

For as small as Lithia Minor was, it had a lot going on. The fish included all of the species that occurred in Lithia Major, with the exception of seminole killifish, but it had relatively more native fish than its larger cousin. Perhaps the replacement of the big sandy plains with a rocky substrate accounted for the lower percentage of blackchin and blue tilapia, both of which dig pit-like nests 9https://www.fishbase.se/summary/1412). Adult spotted tilapia, which I did not see in Lithia Major (I only saw loads of juveniles), also were present in Lithia Minor.

The Lithia Minor headspring, looking downstream (top) and back at the vent (bottom). In the top photo, spotted tilapia that were transitioning from juvenile to adult are in the center of the frame, identifiable by the bars that were shortening into spots. Above the spotted tilapia was a native bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus) and some blue tilapia. In the bottom photo, all of the fish were spotted tilapia and all were juveniles with the exception of the fish with the spotted yellow side.

I picked up a couple of new fish (to me) at the Lithia Minor headspring: a Rio Grande cichlid (Herichthys cyanoguttatus) and an African jewelfish (Hemichromis letourneuxi).

A Rio Grande cichlid (top) and two African jewelfish (bottom) at the Lithia Minor headspring.

A video of an armored catfish scraping algae off of the rocky side of the Lithia Minor vent. Also visible were two largemouth bass, some spotted tilapia, a couple of bluegill sunfish (barred with black dot on dorsal fin), and a Rio Grande cichlid in the foreground.

In one of the most fun and scary clips of the project, two adult spotted tilapia herd a cloud of juveniles down the run (hopefully, they are visible in the small version of this clip!). According to FWC, spotted tilapia have sticky eggs (~2000!) that they attach to hard surfaces (https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/profiles/freshwater/spotted-tilapia/), so it makes sense that they would be spawning in this spring rather than in the sandy Lithia Major.

Spotted tilapia parents guarding their young in Lithia Minor.

Buckhorn Spring

Buckhorn Spring is several miles downstream of Lithia Springs, on a northward curve of the Alafia River before it heads to Hillsborough Bay. To find the spring, I floated downstream from the Alafia River public boat ramp

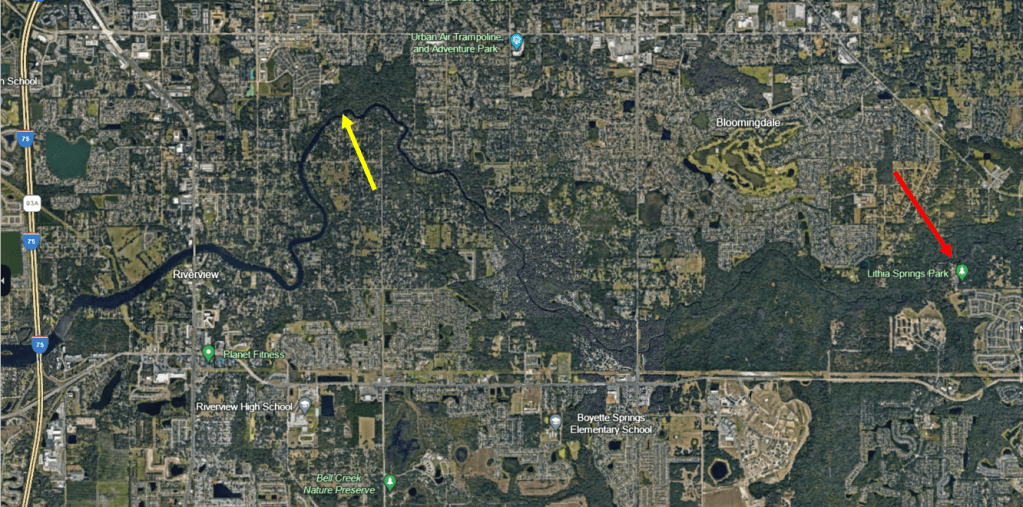

Google Earth image showing the location of Buckhorn Spring (yellow arrow) relative to Lithia Springs (red arrow).

A lower elevation photo showing the location of the headspring at the top right of the photo and the plume of Buckhorn Spring entering the Alafia River (yellow arrow).

The spring was of my favorite type, narrow and sandy with full canopy. However, it also had about a million snags, so trying to get all the way up to the headspring was ambitious, particularly given that I read that the headspring is owned by Mosaic Phosphate Company. I had planned to paddle up to the fence and take a picture, but alas after portaging over many, many trees, I realized that I would likely run out of time before I made it up there. I turned around about halfway up the run. Buckhorn Creek is reputed to have several springs that contribute to its flow and I am fairly sure that I found one of them, but it appeared to not be flowing.

This bridge crossed Buckhorn Creek a short way up the run from the Alafia River.

One of the many obstacles, although this one was relatively easy to get past.

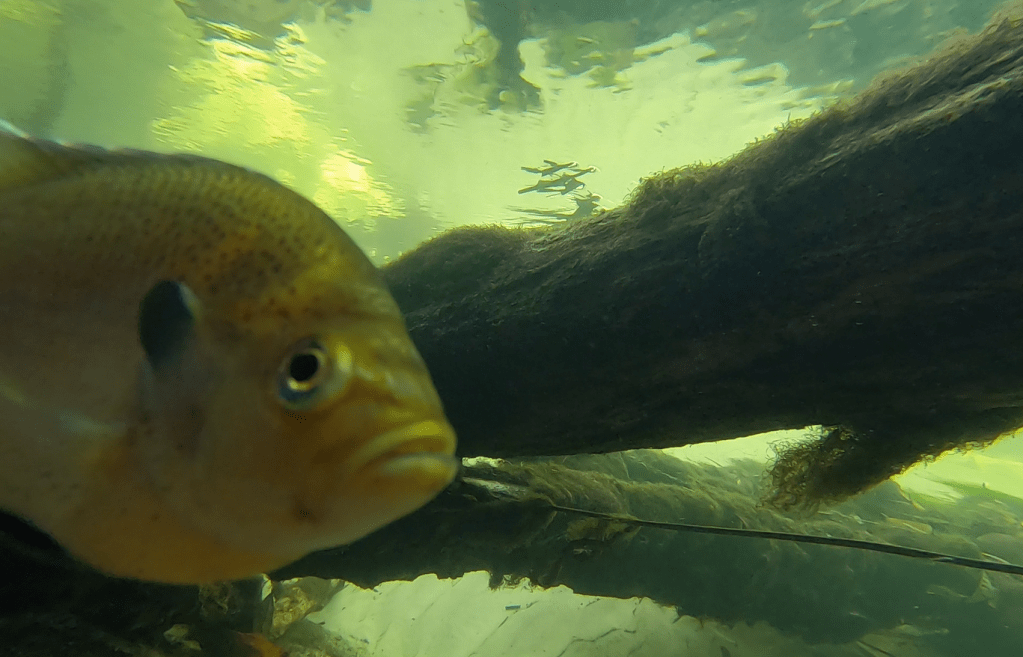

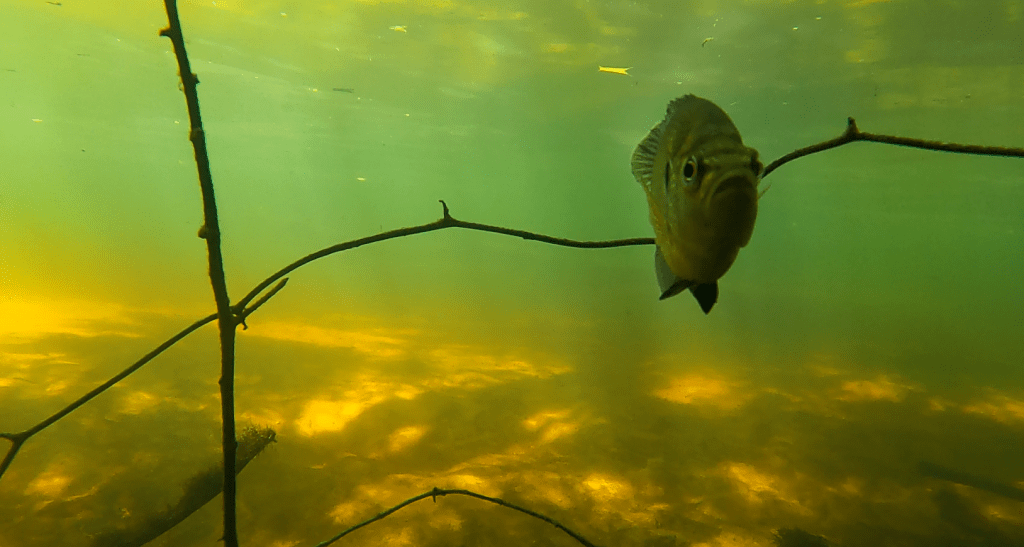

Along a lot of the run, I observed no fish from the boat. The water flowed very fast and scoured the run down to the sand in many areas. At the spot where I turned around, about halfway up the run, I captured no fish on the cameras either, but as I worked my way downstream, I picked up the occasional sunfish and lots of shiners working very hard to stay in place in the vicinity of flow-blocking structure.

Shiners working hard to stay in place about 1/3 of the way up the Buckhorn Spring run.

A spotted sunfish hanging out around the flow-breaking structure of logs.

Downstream of the bridge, the spring was deeper and the flow was a little slower. The fish did not have to work as hard to stay in place and so I recorded lots of shiners as well as a largemouth bass and a spotted tilapia.

A largemouth bass in the upper corner of the image with a huge shoal of shiners.

A spotted tilapia inspecting the camera.

Where the spring water met the river, the light became golden and spotted sunfish and tilapia milled around, entering the spring and returning to the river.

A spotted sunfish at the confluence of the spring and the river.

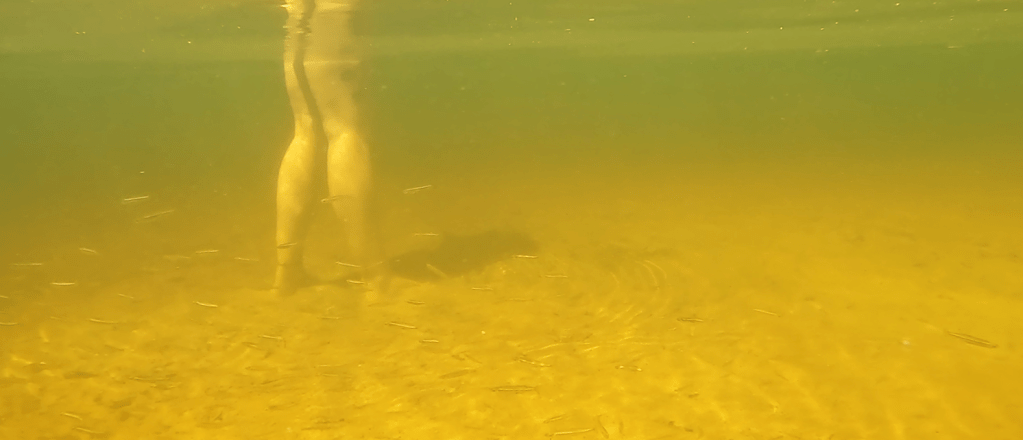

The point where the spring enters the river is apparently a popular spot for recreation. I watched three different parties spend some time there in the short time that it took me to film the end of the spring. One woman told that I should come out and film the “fish tornado” around her legs. It turns out that the tornado was composed of silversides; usually when I see silversides, they are golden silversides (Labidesthes vanhyningi) and I see them alone or in pairs. Inland silversides (Menidia beryllina), on the other hand, form schools, so perhaps I would have another species to add to the list if I could be sure of the identification in the murk.

Recreators at the confluence of the spring and the river (top) and the “fish tornado” of silversides (bottom) in the river just off the point where the boat is parked in the top photo.

Spring characteristics and water quality

The three springs described in this post differed greatly in morphology, from very wide to very narrow. Two of the three were sandy; one was rocky. Two had moderately high flow; one had very high flow. Despite these differences, all three had relatively little algae and all had loads of exotic species. All three were on the slightly warmer side for Florida springs (24.1 to 25.9oC).

I was not able to measure oxygen at the headspring of either Lithia Major or Buckhorn Spring. In its short run, Lithia Major ranged from 2.74 to 5.69 mg/L and, in its longer run, Buckhorn ranged from 3.77 to 5.28 mg/L. Lithia Minor ranged from 1.75 mg/L at its headspring to 3.88 mg/L near its confluence with the river. The conductivity of these springs was about double the values for springs that I visited farther inland (Lithia Major ~560 microS/cm, Lithia Minor ~570 microS/cm, and Buckhorn ~540 microS/cm), but still low relative to the springs with tidal influences. The values for all of these variables seem typical to good for Florida springs.

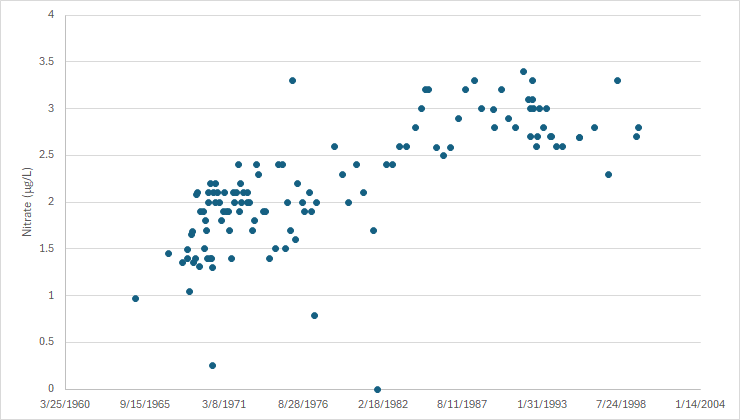

However, the water quality data that I found suggested that all three have experienced massive increases in nitrate, despite their lack of abundant algae. The USGS collected nitrate data for Lithia Major from 1965 to 1999 (why did they stop?) and these data show a huge increase in nitrate up to the late 1980s, but the nitrate concentrations in 1965 already were quite high (if the background nitrate concentration was on the order of 0.35 mg/L). What were background concentrations of nitrate in these springs if concentrations were already so high in 1965 and what has happened since 1999?

Increase in nitrate in Lithia Major from 1965 to 1999 (data from USGS NWIS, https://maps.waterdata.usgs.gov/mapper/index.html).

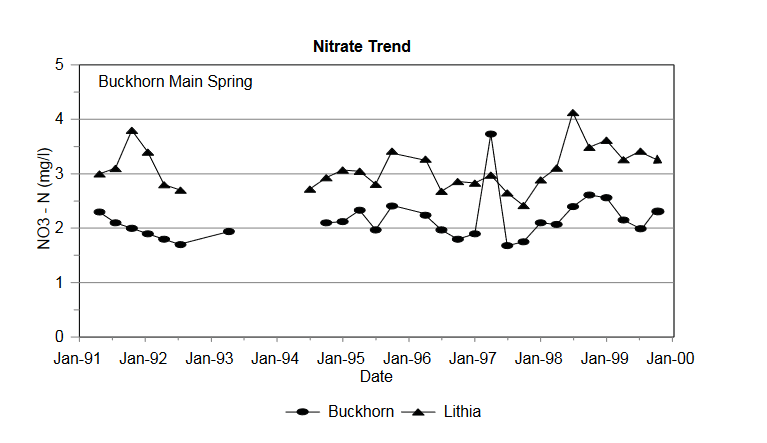

Data in a SWFWMD report for Buckhorn from the early 1990s to 1999 suggest that its nitrate concentrations were only a bit lower than those of Lithia. The only data that I could find on USGS NWIS for Buckhorn were from 1972 and suggest that nitrate was 0.9 mg/L at that time.

Comparison of the nitrate concentration of Buckhorn and Lithia Springs in the 1990s (figure from: https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/sites/default/files/medias/documents/springs.pdf)

A SWFWMD report from 1993 indicated that the source of the nitrate in Lithia and Buckhorn Springs was “inorganic fertilizers applied to citrus, with minor animal-waste [dairy] contributions” (https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/sites/default/files/medias/documents/LithiaBuckhornSprings.pdf). It also reported that the “minimum travel time of groundwater in the fracture [limestone fractures in the aquifer] is approximately 1 mile every 5 years”. According to a Hillsborough county website, the proportion of land in agriculture has dropped from 27 to 13% from 1990 to 2020 (http://hillsborough.wateratlas.usf.edu/watershed/geography.asp?wshedid=1&wbodyatlas=watershed), but I could find no data older than 1990. If land in citrus was taken off line, how long would it take the nitrate to stabilize or decline if other land uses contributed less nitrate? The report indicated that bringing 11,000 septic online by the early 1990s might affect the spring nitrate concentrations. It would be interesting to know what those concentrations are now.