People say that Florida has no seasons, but this photograph says winter to me. The photo is centered on the homemade diving platform at Big Blue Spring on the Wacissa River. The trees, usually so lush, have few leaves, the shadows are long, and the swimmers have been gone for months. Winter on Florida springs is peaceful.

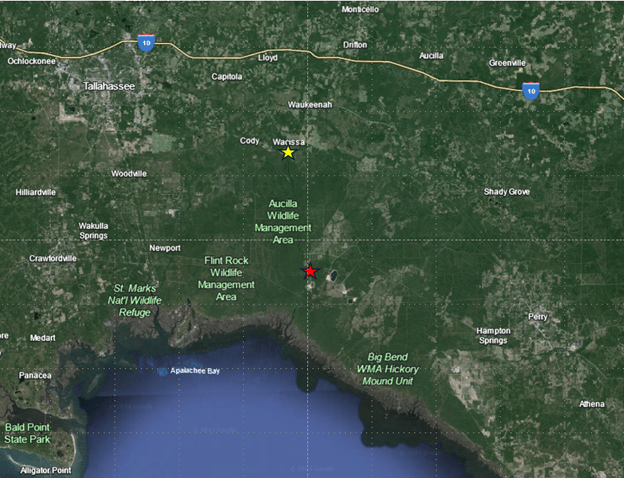

The Wacissa River starts east and slightly south of Tallahassee. It flows through the Aucilla Wildlife Management Area, passing between the Flint Rock Wildlife Management Area and the Big Bend Water Management Area. The drive out to the spring winds through forests or, if coming from Tallahassee, the occasional pasture. About 12 miles downstream from the start of the Wacissa, the river joins the Aucilla River to flow into the Gulf at Apalachee Bay. Together, these two rivers have been categorized as an Outstanding Florida Water.

A map of the Big Bend region that it is the home of the Wacissa River. The yellow star indicates the location of the river’s origin; the red star indicates where the Wacissa joins the Aucilla.

Like the Chassahowitzka, the Wacissa is a river made of springs. It, too, starts with a small spring that feeds into a wide run that meanders to the Gulf, although its meander is roughly 3 times longer. The small spring at the start of the Wacissa, Horsehead Spring, is narrow, somewhat brown, and thick with plants. At the headspring, I could not see the vent at the bottom. The spring seemed more like a hole in the plants than the rocky crevice that was undoubtedly underneath the dark water.

Map showing the location of the first two springs, Horsehead Spring (orange star) and the larger vent downstream at the start of the river proper (blue star).

The headspring for Horsehead Spring (top) and light streaming down from the distortion made by my paddle at Horsehead headspring (bottom).

Once I left the Horsehead headspring, the trees converged over this lovely little spring run. The run was so filled with plants that I had to find holes in the plant cover to get a good enough field of view to film. Some of these plants were eelgrass (Vallisneria americana) and some were nonnative hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata), as seen in the video below.

Shiners and bluefin killifish (Lucania goodei) streaming past the camera at the headspring of Horsehead Spring.

In this small spring, I was rewarded with a fish species new to me, the metallic shiner (Pteronotropis metallicus). Shiners are very hard to identify on film because many of the characters that are needed for a good identification are too small and obscure to see at a distance, but this species has a very wide black stripe on its side and a dark dorsal fin etched in white and orange on the outer edge. As they darted around the plants, the fish popped their dorsal fins up and down, inadvertently signalling to me their species.

Metallic shiners in Horsehead Spring run.

As soon as I floated out of Horsehead Spring, I found myself over a spring vent that I had not realized was there. It was large and dark, but provided substantial flow to the river. I noticed the spring as I floated over it because it, too, looked like a round hole in the plants. In fact, the whole river upstream was thick with plants; the plants were so thick that the birds were walking on them as if on land.

Eelgrass waving in the flow of the river (top) and a little blue heron (Egretta caerulea) standing on the thick hydrilla in the river (bottom).

This thick plant life, both native and nonnative, provided cover for small fish. In contrast to the Chassahowitzka, which had virtually no plants in the main river, lots of predators, and very few small fish, the Wacissa was teaming with small fish. Every video showed some combination of 30-50 shiners, killifish, and livebearers like mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki). Large predators, like largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) or longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus) were relatively rare in the videos of either the main river or the many springs that fed into it along its upper length.

A rare group of three largemouth bass patrolling (top) and a largemouth bass scaring shiners into the vegetation (bottom). The shiners wink back into view after the bass moves along.

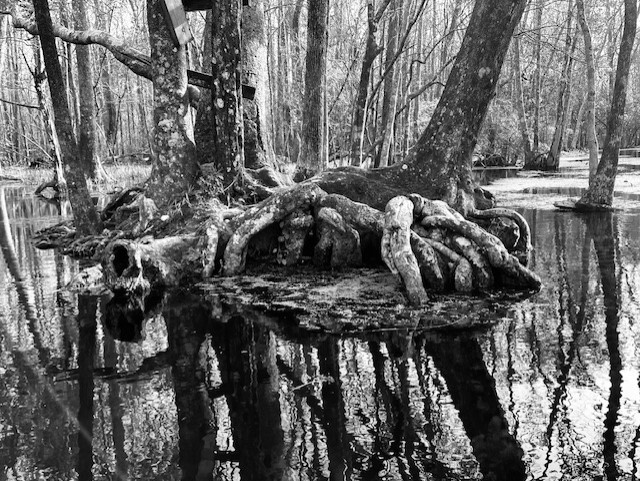

Flooding back into the forest also provided cover for fish. Hurricane Idalia passed over the area in August 2023 and the flood waters still had not completely receded in February 2024. Florida is so flat, its water table is so shallow, and there often is so much precipitation in the rainy season that floods can last a very long time. When the water penetrates back into the woods, the cypress knees and shrubs can provide extra cover from predators for small species.

The homemade diving platform above this knot of tree roots on Big Blue Spring suggests that it is likely on dry land in the summer when the floodwaters recede.

After I finished filming in the main river, I moved into some of the many springs that contribute water to the main flow: Big Blue, Little Blue, Buzzard Log, Garner, and Minnow.

Flooded forest (top) and duckweed (Lemna sp.) so thick that my kayak made a trail (bottom) in Minnow Spring.

I have been thinking lately about how small side springs and flooded forest might contribute to the overall diversity of larger systems. When I filmed back in the side springs of the Wacissa, many of the fish that I observed were the same species as in the main stem of the river. However, I also found some unique assemblages and species. Back in the side springs, I observed more least killifish (Heterandria formosa), our smallest fish species in Florida, than I have ever observed together. The specific epithet of this species references the family name of ants, Formicidae, undoubtedly because of their small size. I also observed a chain pickerel (Esox niger), a large predatory species that I have only caught on camera once in all of the video that I have collected to date.

Tiny least killifish above the slightly larger shiners at Minnow Spring (top) and a chain pickerel at Garner Spring (bottom). The camera at Minnow spring was back in the flooded forest and there was a lot of dissolved and particulate “stuff” in the water. The camera a Garner Spring captured a lot of live and dead algae and plants.

And much to my surprise, I also caught an entirely new type of organism for me: an eastern newt (Notophthalmus viridescens). This animal has a relatively unique life history, with a juvenile aquatic stage, followed by a juvenile terrestrial stage, and finally an adult aquatic stage (https://nationalzoo.si.edu/animals/eastern-newt). Given that I collected the video of this species at two different locations (right off the boat ramp and in Big Blue Spring), it is likely that there are a lot of newts in the system.

Eastern newts in Wacissa River springs.

The fact that the Wacissa River flows through Wildlife Management Areas likely contributes to its good water quality. The nitrate concentrations published by the US Geological Survey are among the lowest that I have observed for Florida springs (0.16-0.33 mg/L). The dissolved oxygen concentrations they published are relatively high (4.9-8.3 mg/L) and my measurements were in a similar range. The conductivity of the river and its springs, both published data and my data, are much lower (0.26-0.30 mS/cm) than what I measured in some of the Chassahowitzka springs (5-10 mS/cm), undoubtedly due to the greater distance between the Wacissa springs and the Gulf. Conductivity is a measure of ion concentrations in water, kind of the freshwater version of salinity. Salinity is a measure of sodium and chloride, whereas conductivity encompasses the broader range of ions typical of freshwater. To give some context, the conductivity of sea water is 3-6 S/cm, so several orders of magnitude higher than in the saltiest springs that I have measured. It is likely that the lower conductivity and the greater distance to the Gulf explains the exclusively freshwater assemblage that I observed on the Wacissa in contrast to the Chassahowitzka.