May 2024

I started my fish-filming journey seven years ago in Rainbow Springs, so it seems appropriate that I end these posts there as well (at least for now!). With its clear, blue water and many, many vents spouting water and sand, it is a spring-enthusiast’s dream.

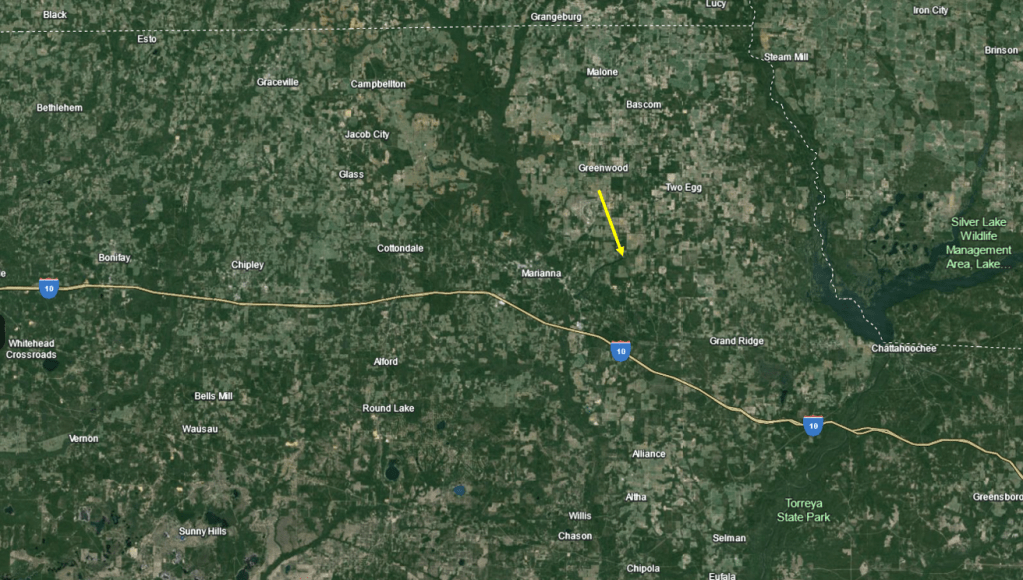

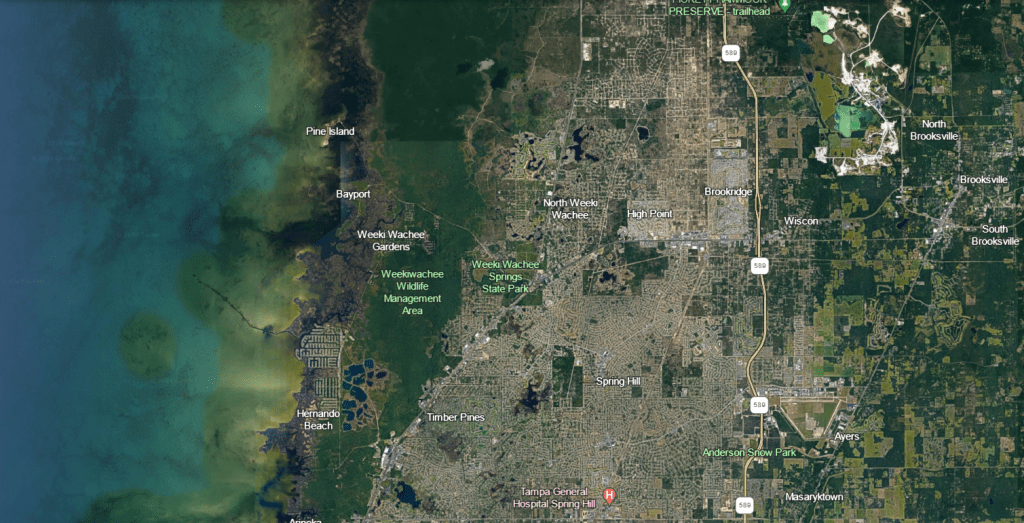

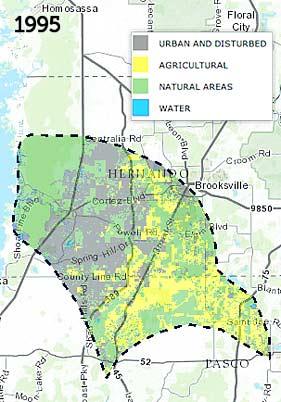

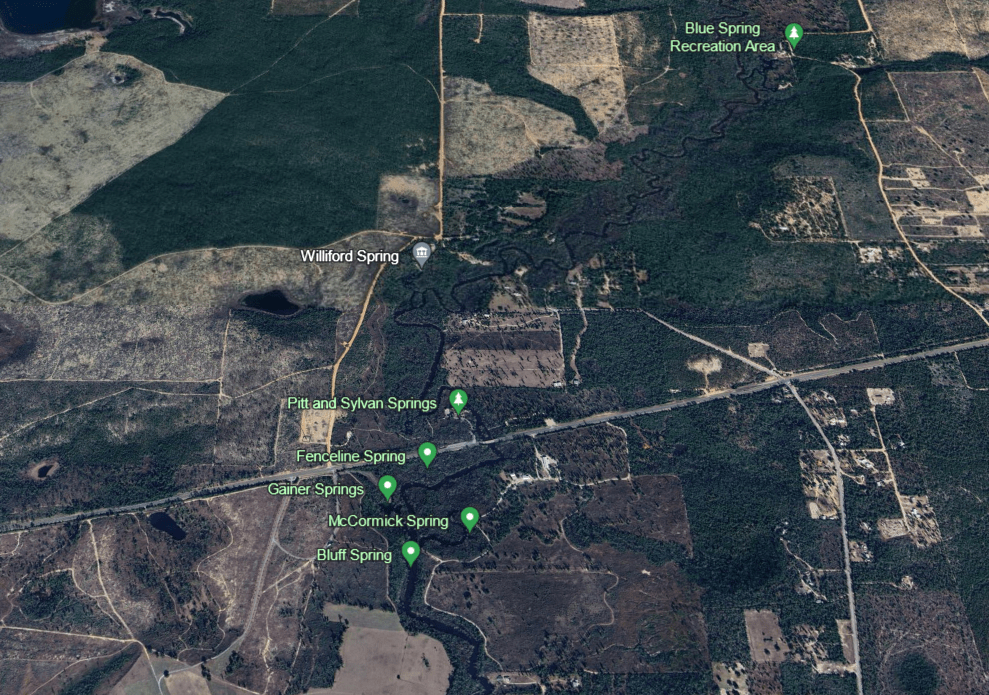

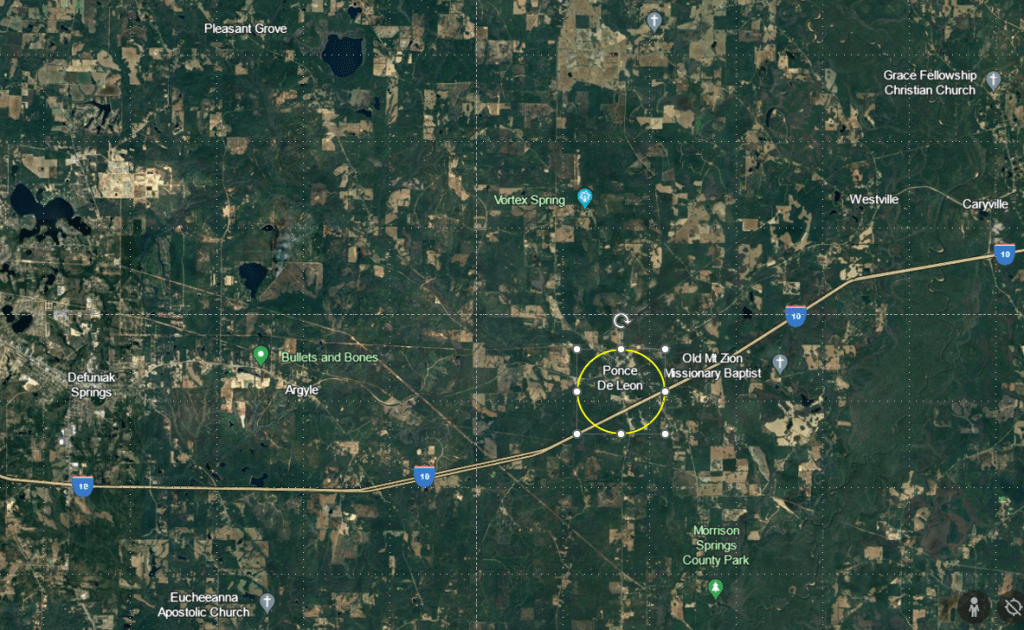

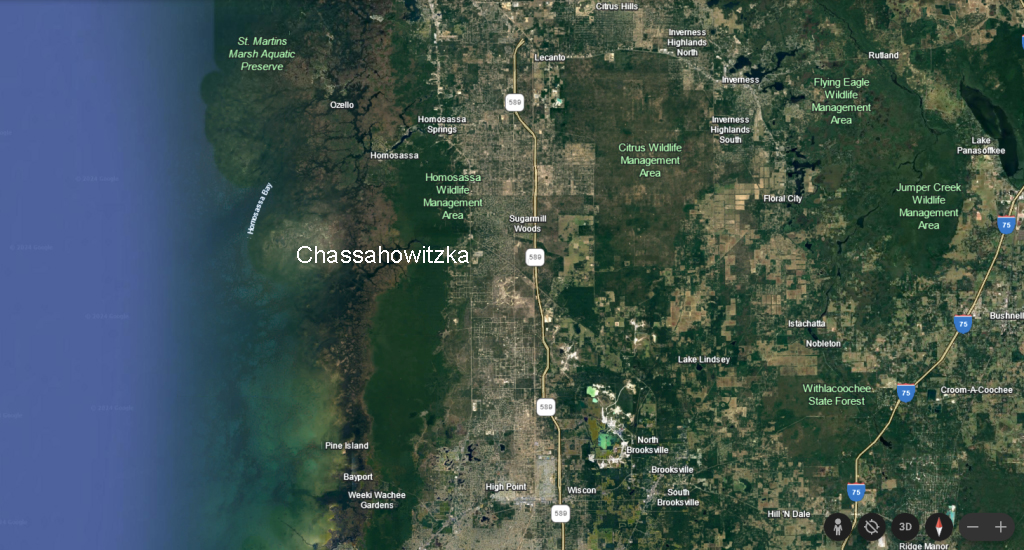

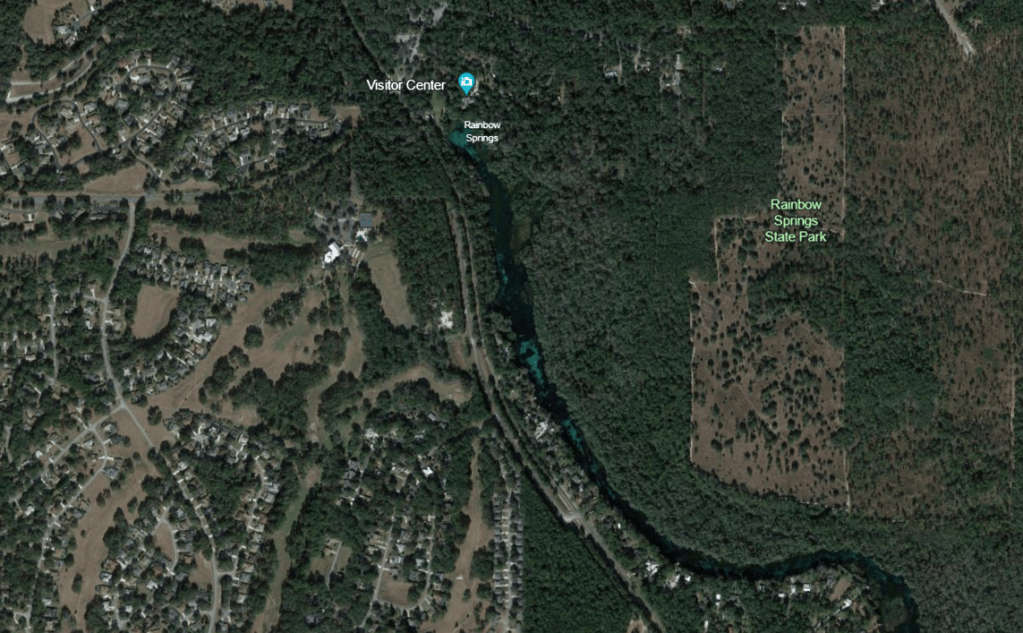

Rainbow Springs is in an agricultural/residential area southwest of Ocala. The closest town to Rainbow Springs is Dunnellon, which did not feel appear to have grown a great deal since I stayed there seven years ago, although I did not spend a lot of time there on either trip. The neighborhoods just north and west of the spring, on the other hand, seemed to have grown substantially in the intervening years.

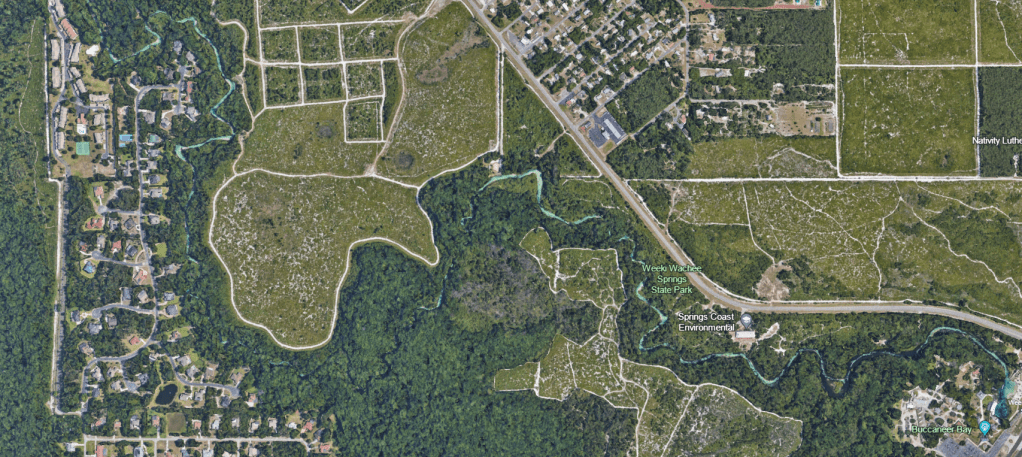

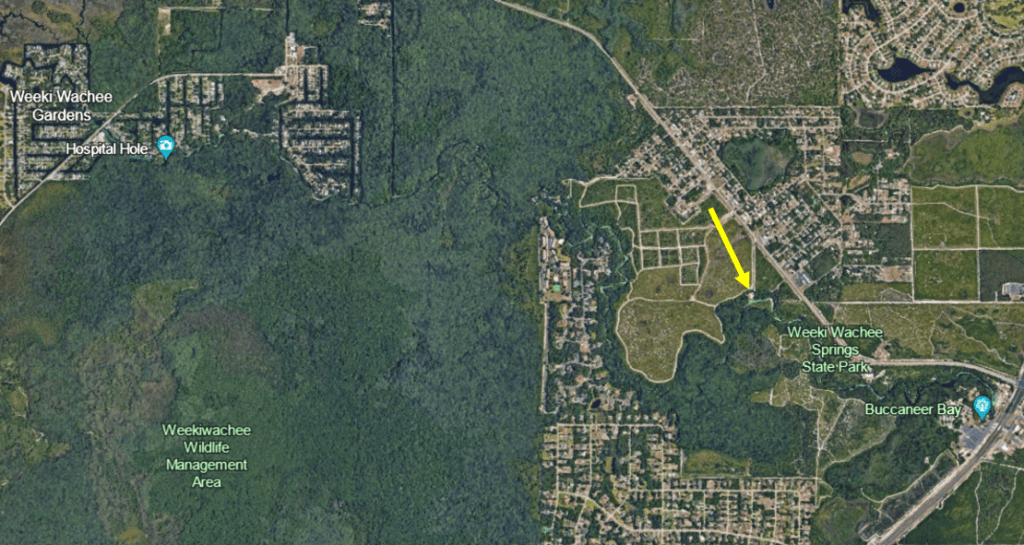

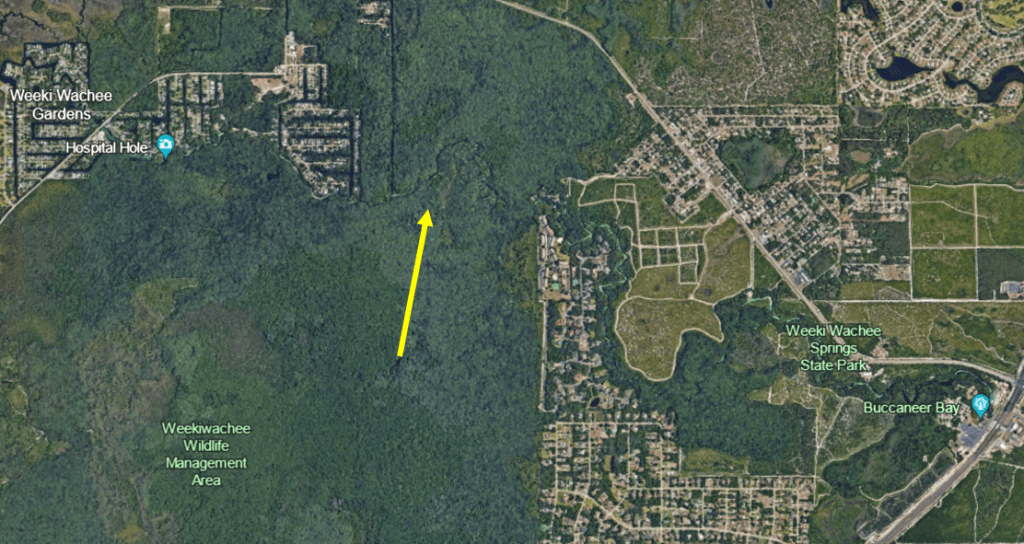

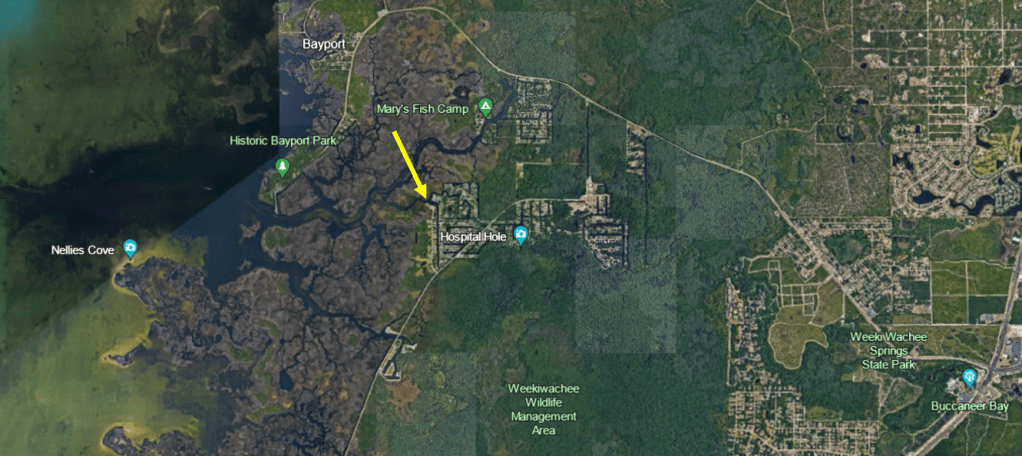

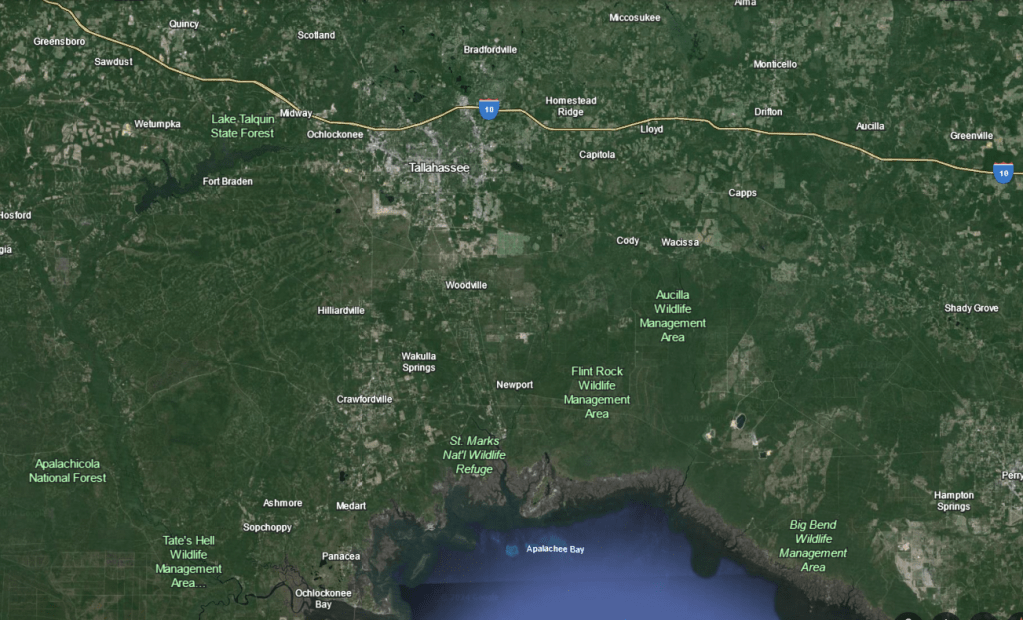

Google Earth images of the landscape around Rainbow Springs and of the spring itself. The blue of the run is obvious even from these high elevation images. The darker areas are thick beds of plants.

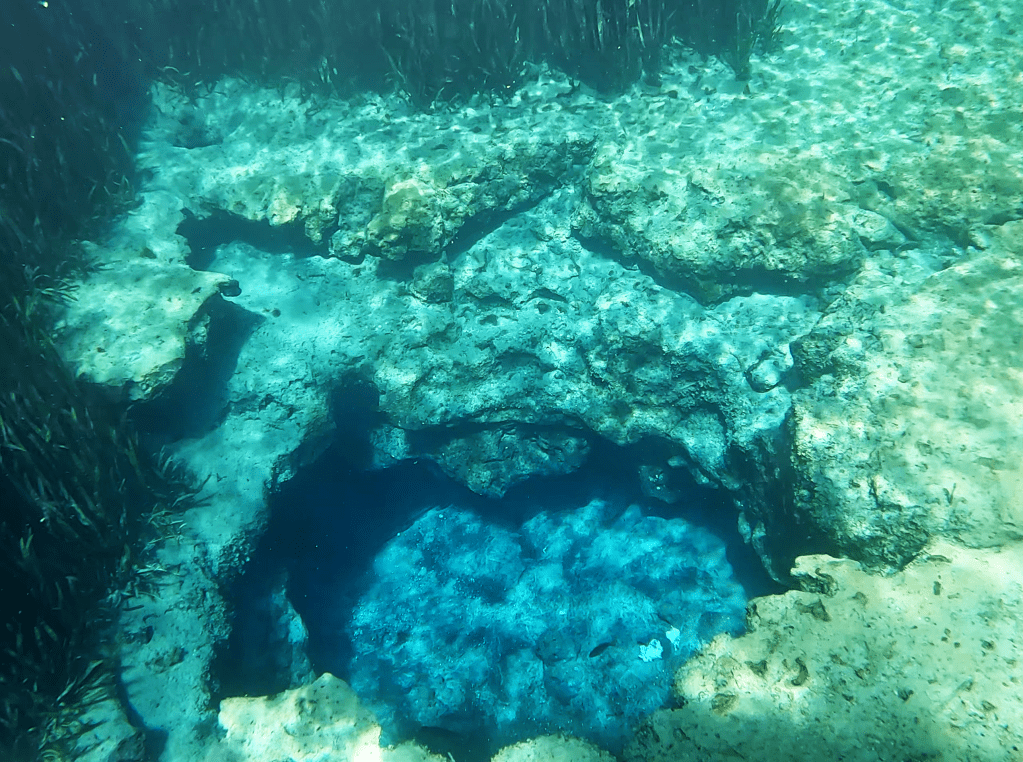

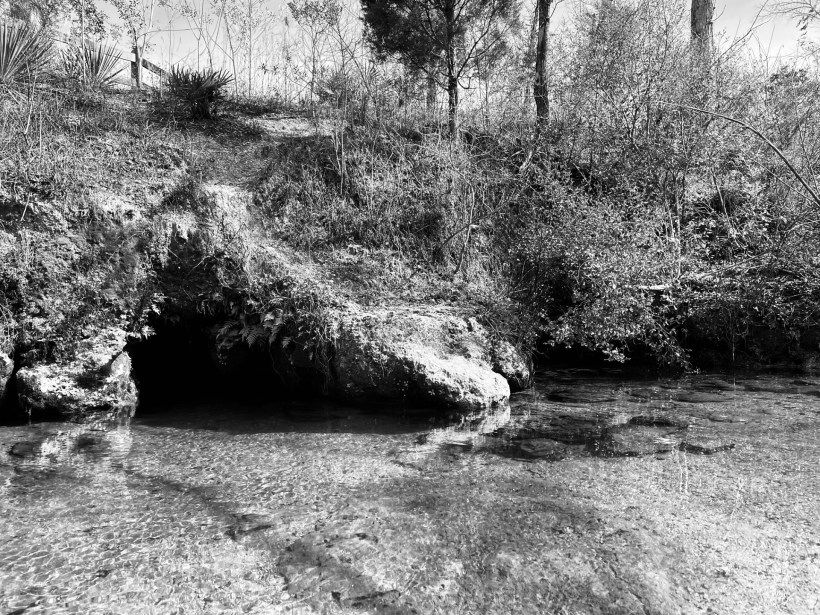

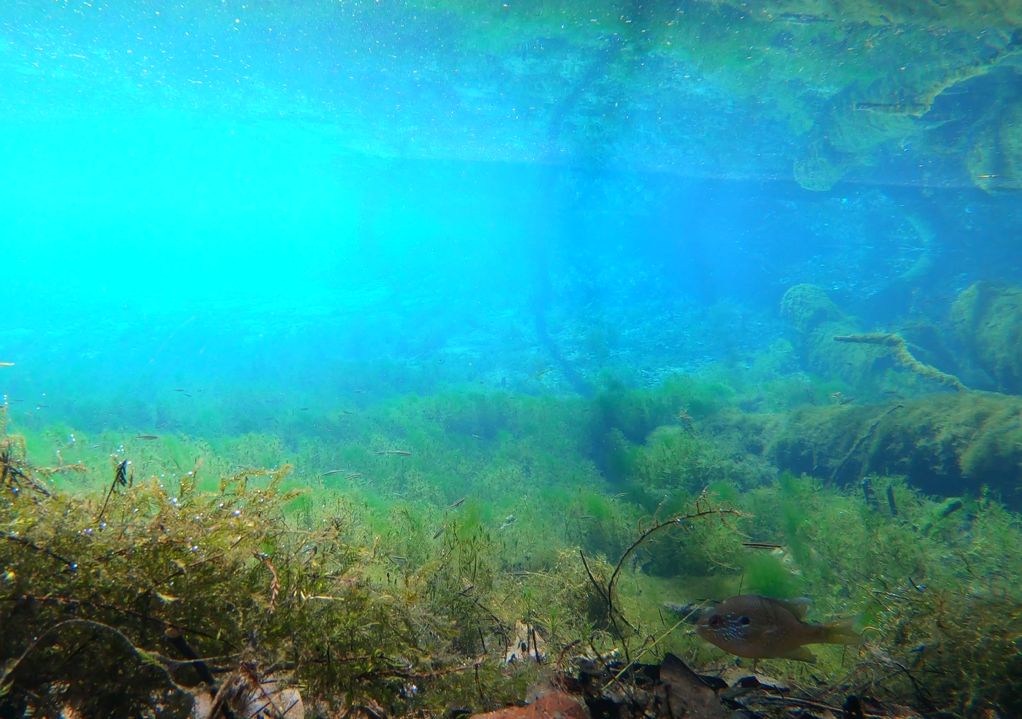

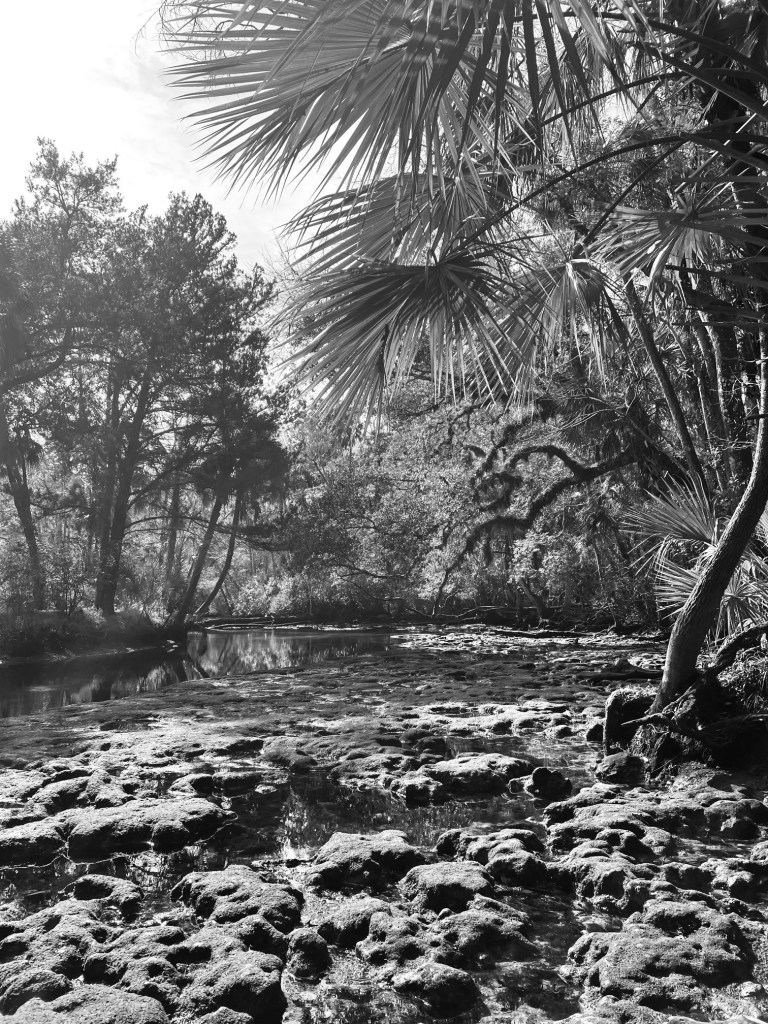

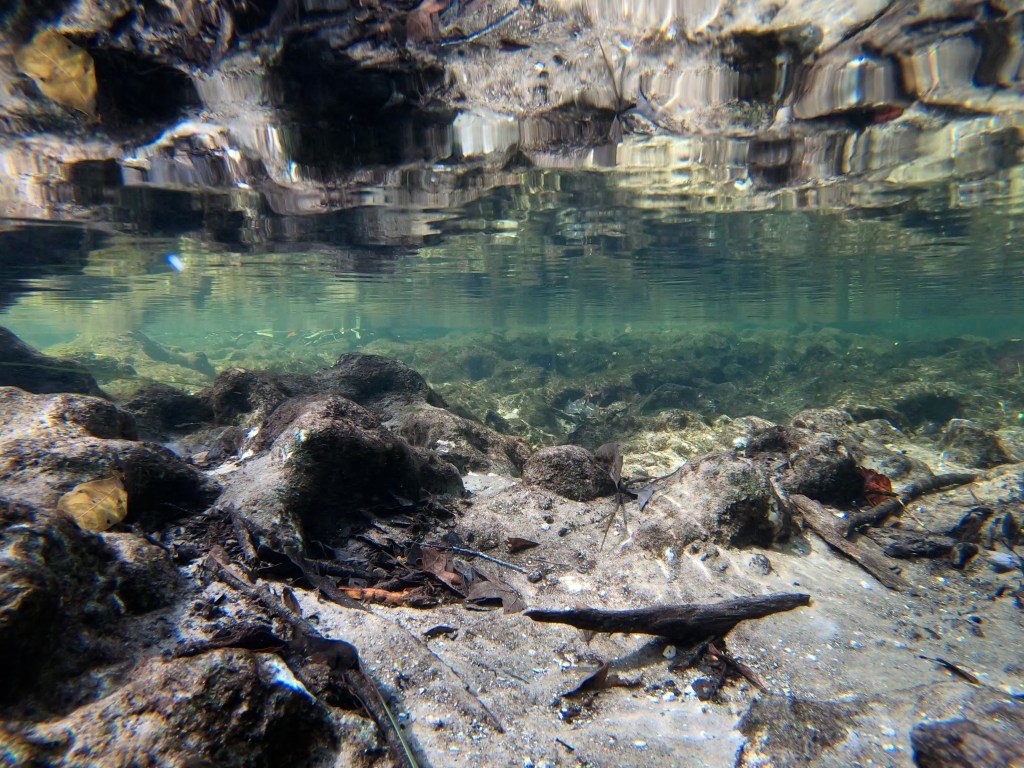

The headspring of Rainbow is actually a collection of smaller springs that collectively form a large blue pool, scattered with rocks and ringed by submerged and emergent plants.

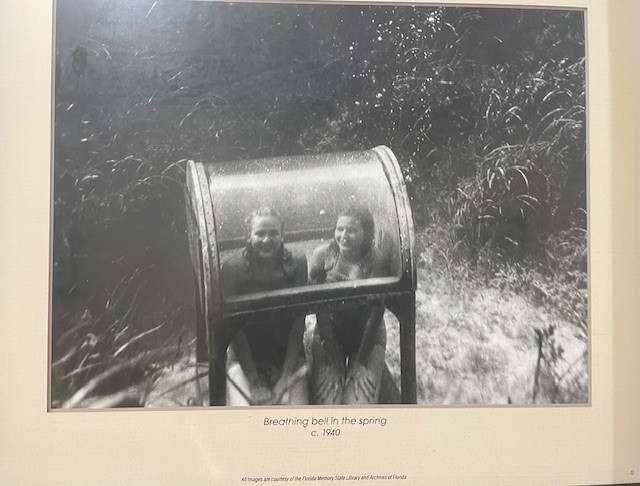

View of the headspring pool, looking back toward the swimming area. It is a blue to which swimming pool owners aspire.

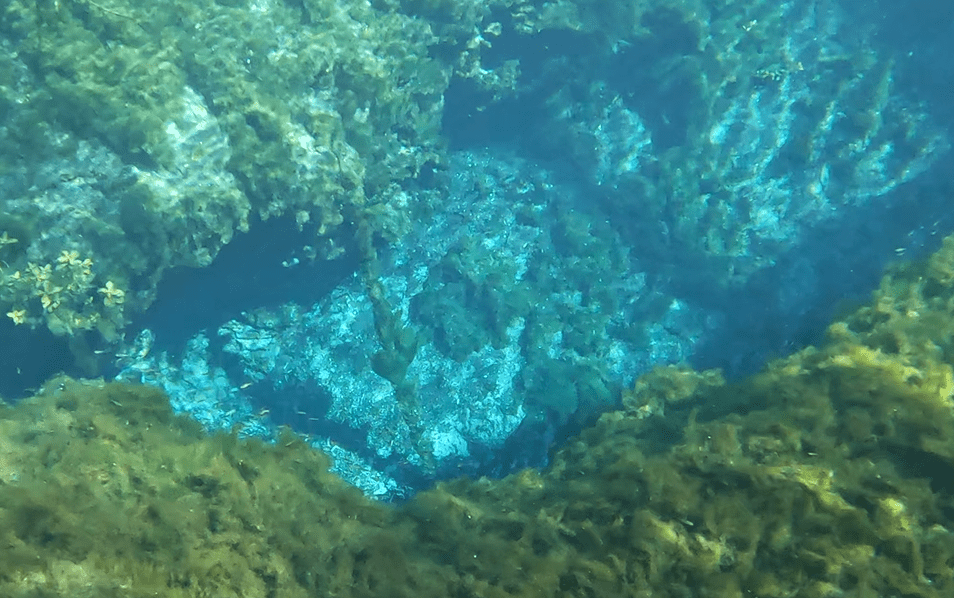

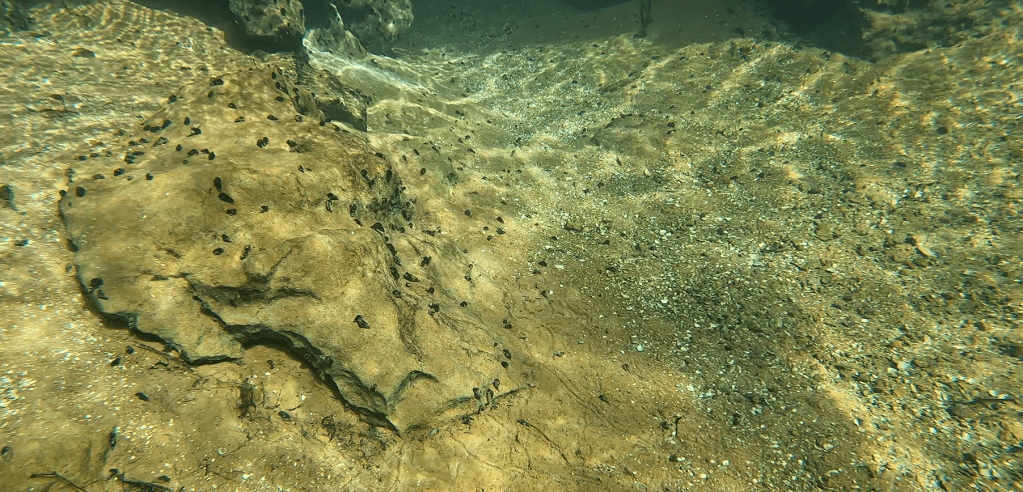

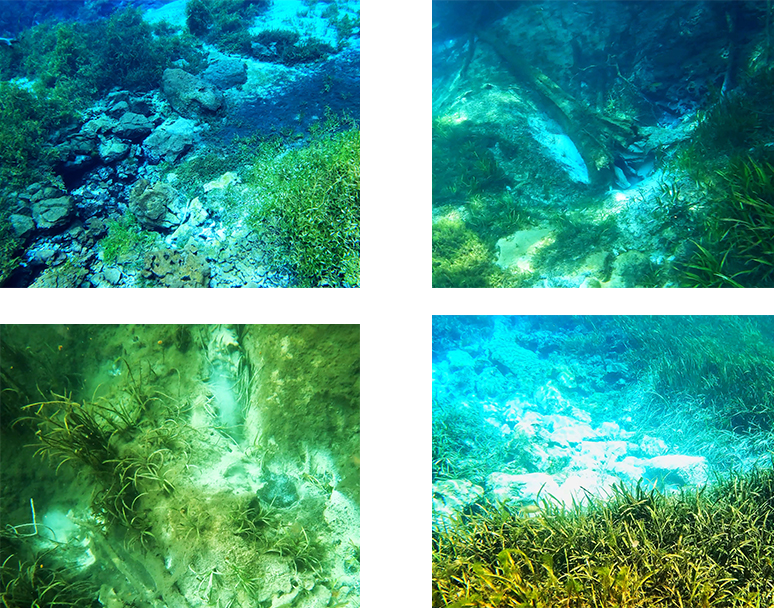

Underwater views of several vents or sand boils, starting with one of the headspring vents in the upper left-hand corner and ending with cloudy plumes coming from sand boils downstream in the lower left-hand corner.

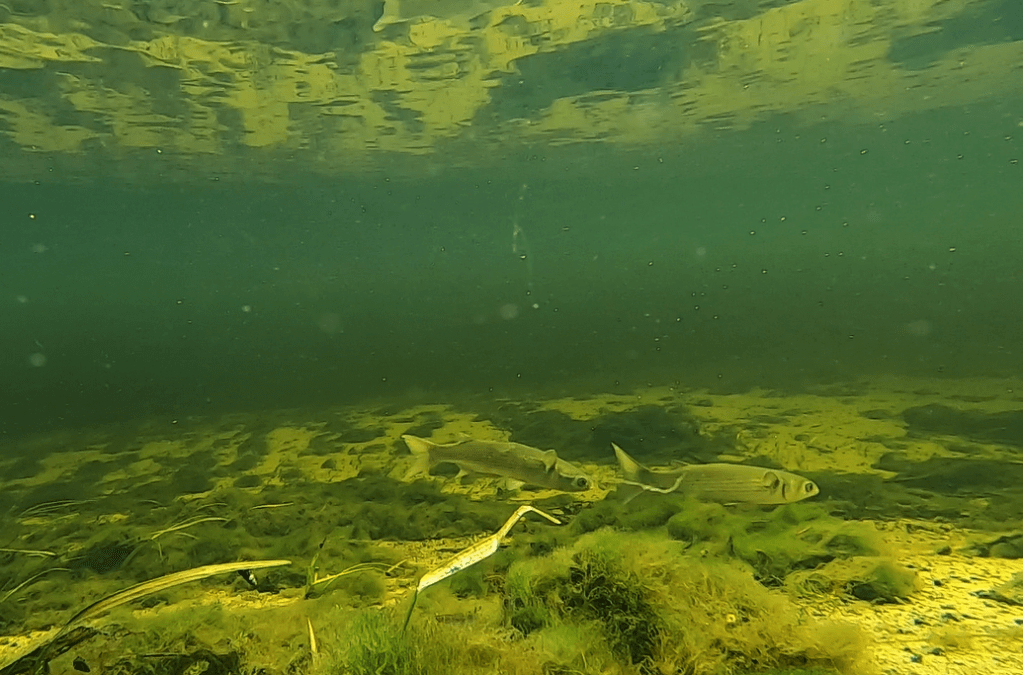

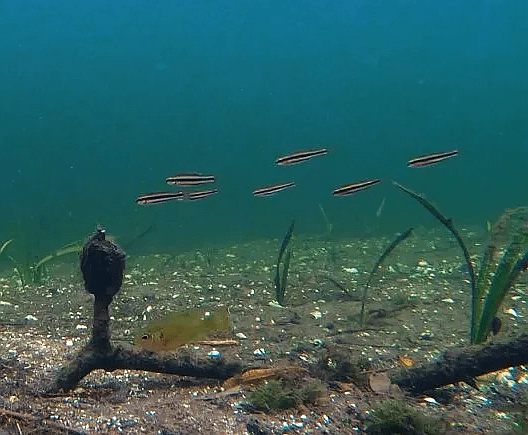

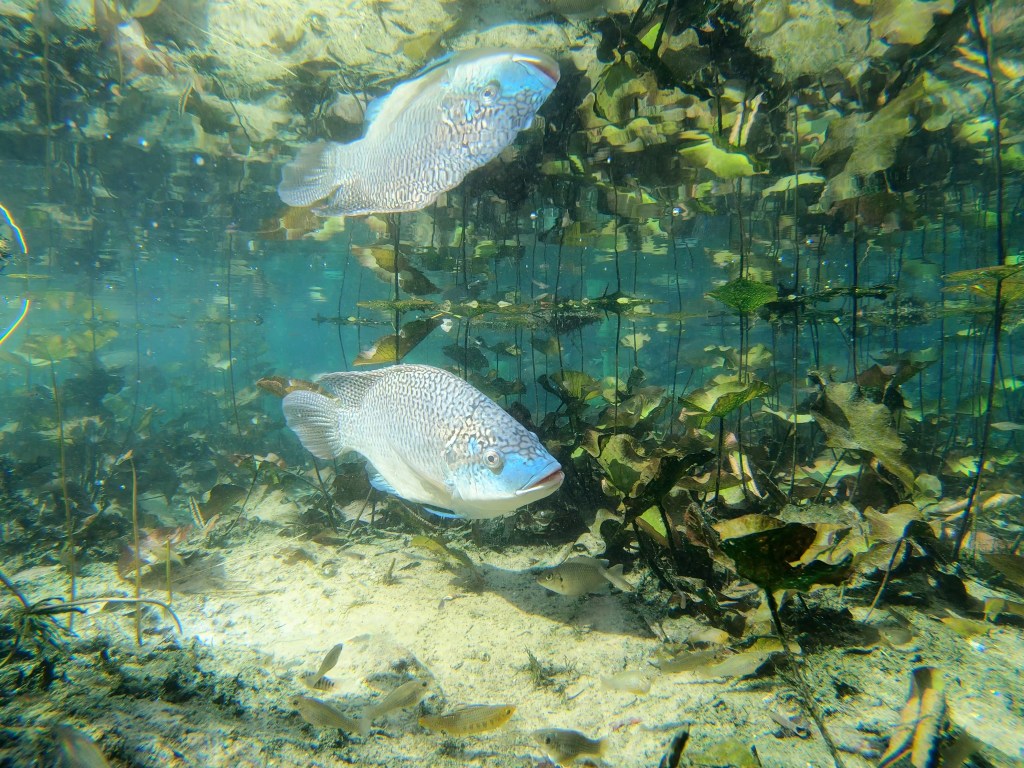

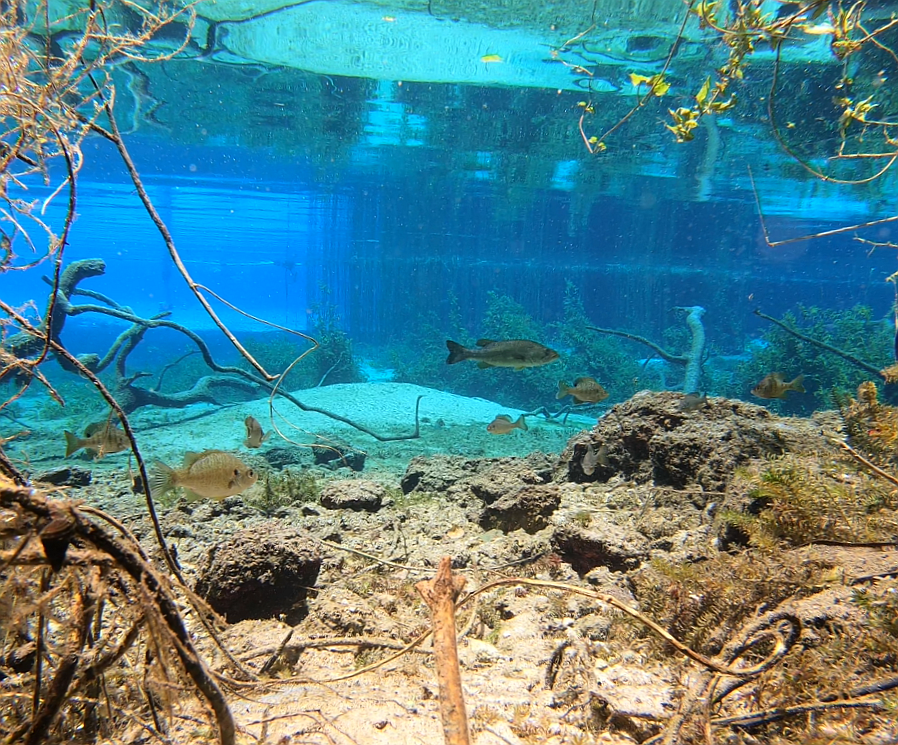

Filming fish is both easy and hard at Rainbow. The clear water makes the fish easy to see and identify, but its depth makes it hard to set cameras. The vistas are stunning.

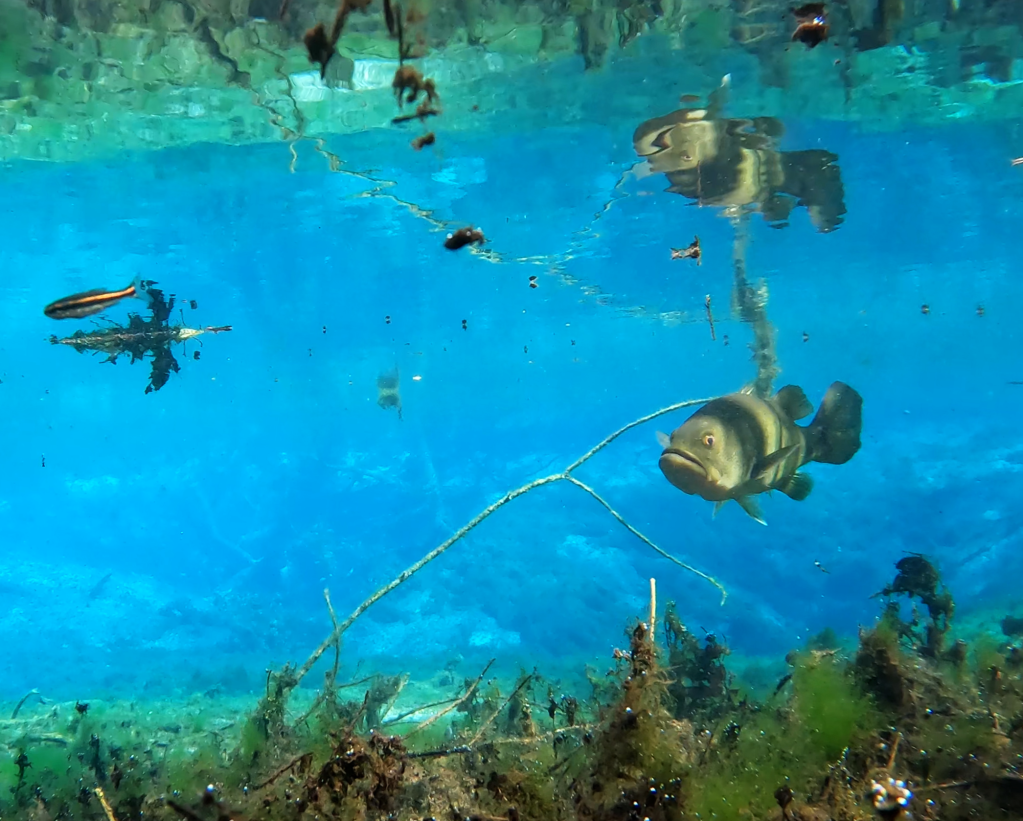

A largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), a redear sunfish (Lepomis microlophus), a redbreast sunfish (Lepomis auritus), and some bluegill sunfish (Lepomis machirochirus) up at the headspring.

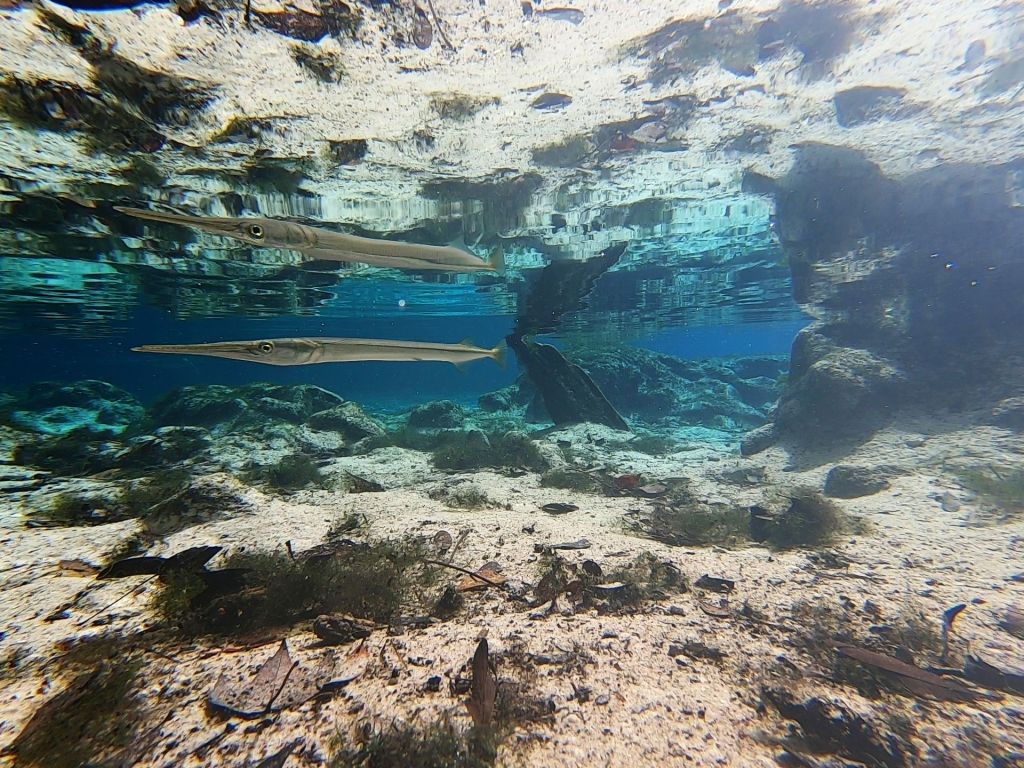

The number of predators in this spring was remarkable. I got at least one largemouth bass is virtually every video that I collected. I even managed to get a bass feeding on video. Just downstream from the canoe launch, a downed tree on the edge of a little bay provided structure for a whole host of longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus). Interestingly, there were gar in that exact same spot seven years ago.

Some impressive predators: a largemouth bass cruising through the site (top) and a video of another feeding (bottom).

A gathering of longnose gar around a downed tree.

The smaller fish, like mosquitofish, shiners, and killifish, were harder to find in attractive poses on video. Given the large number of predators and clear water, they stuck to the areas with more plants, which obstructed my camera view.

Two of the smaller fish species that I recorded: seminole killifish (Fundulus seminolis) and bluefin killifish (Lucania goodei). The red on the tail of the bluefin is just barely visible. They used to be called redfin killifish, but the males often get bright blue dorsal fins when they are breeding. Apparently, the blue is considered more dramatic than the red.

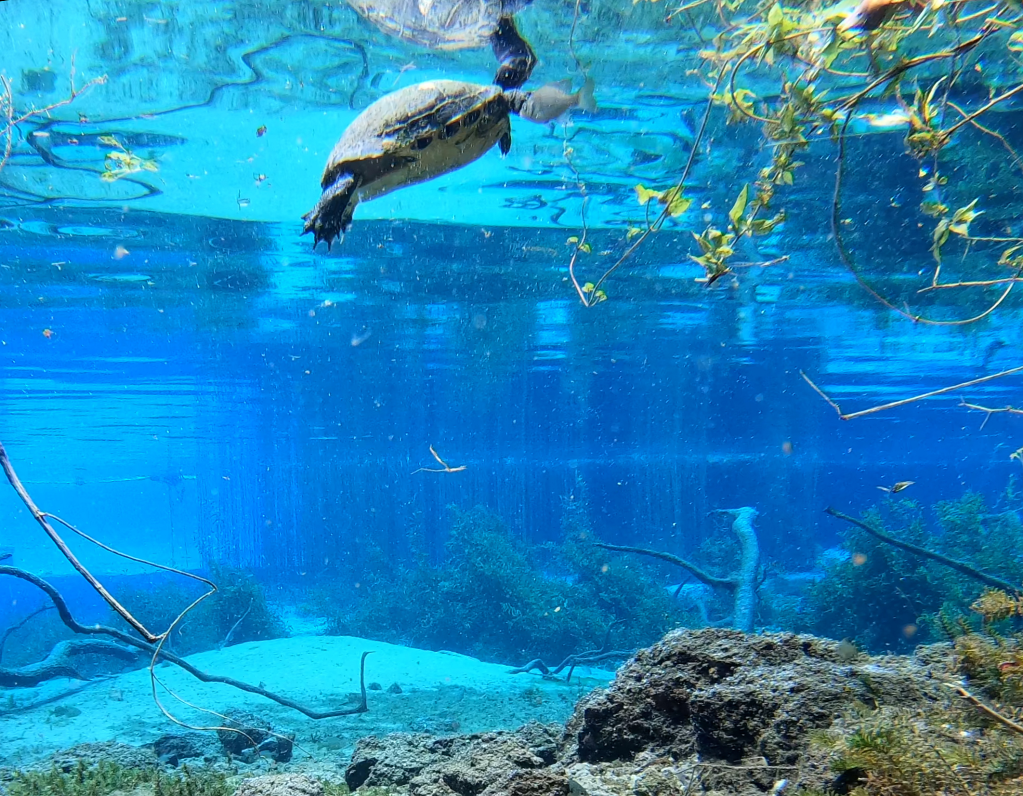

In addition to the number of predatory fish, the number and diversity of turtles was striking. The turtles favored the dense grasses that cover the east side of the run, which is a conservation area off limits to visitors. When I floated past that area, turtles were everywhere, resting on the grasses and swimming between them. However, I got turtles on video all along the run.

Three of the many turtles that I observed in Rainbow Springs, including on the bottom, a Florida softshell (Apalone ferox).

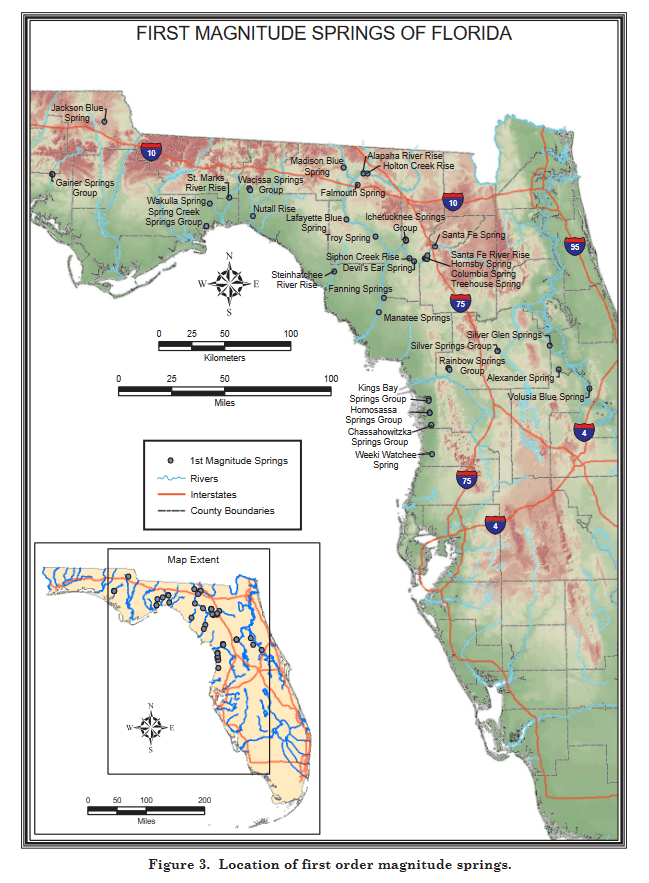

Rainbow Spring is enormous. The first vent alone discharges ~130-320 cfs and all of the subsequent vents add additional flow. When spring #6 adds its flow to the run just upstream of KP Hole, the discharge increases to 297-400 cfs. The 1995 USGS report that ranks the first magnitude springs of Florida puts Rainbow (at 711 cfs with the addition of still more vents downstream) in fourth after Spring Creek Springs, Crystal, and Silver Springs in descending order (https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/1995/0151/report.pdf). The first two springs are a bit more marine, either on the coast or in the Gulf, so that leaves Rainbow competing with Silver for the biggest and clearest inland spring.

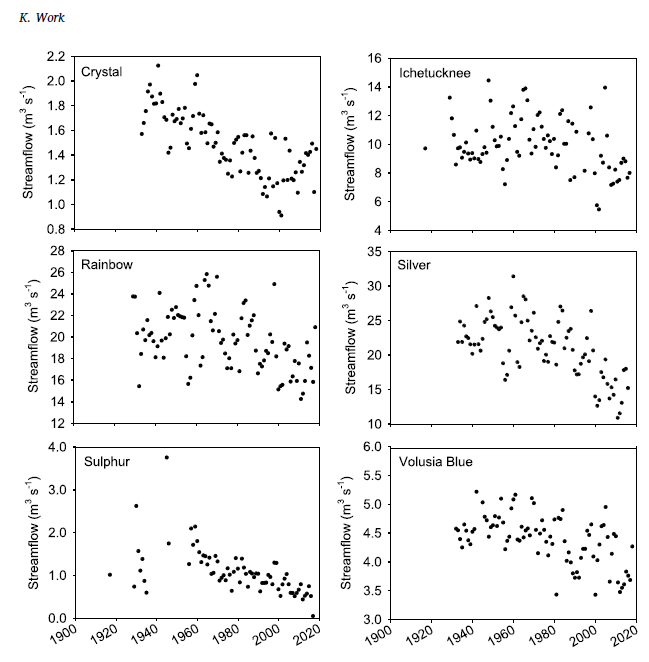

According to the SWFWMD Rainbow Springs dashboard (https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/projects/springs/rainbow/dashboard), the discharge of Rainbow Spring is a little higher than it has been in the last few years. The overall the trend has been downward for decades, not as steep a decline as some big Florida springs, but still.

Data on water quality for Rainbow Springs are hard to find. There is an Minimum Flow and Level plan, but it is not online. There is a Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP, https://publicfiles.dep.state.fl.us/DEAR/DEARweb/BMAP/Springs/RainbowSprings_Final_11302015.pdf), but it only gives the target concentration for nitrate. As a result, my conclusions are based on the SWFWMD Rainbow Springs dashboard and the little bit of data that I collected in 2017 and in 2024.

Rainbow Springs is on the warm side (23-24oC) and the dissolved oxygen is very high for a spring (5.85-7.94 mg/L). It was this spring that made me rethink what is “typical” for Florida springs as these values are more than an order of magnitude higher than the dissolved oxygen measurements that I typically take at the headspring of Volusia Blue. It would seem that the water is barely underground at Rainbow. The conductivity is predictably low (~180-380 microS/cm) for a spring a) far from the Gulf and b) without the underlying aquifer salt lens of some of the St. Johns River springs.

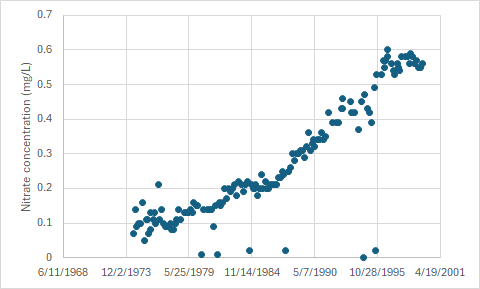

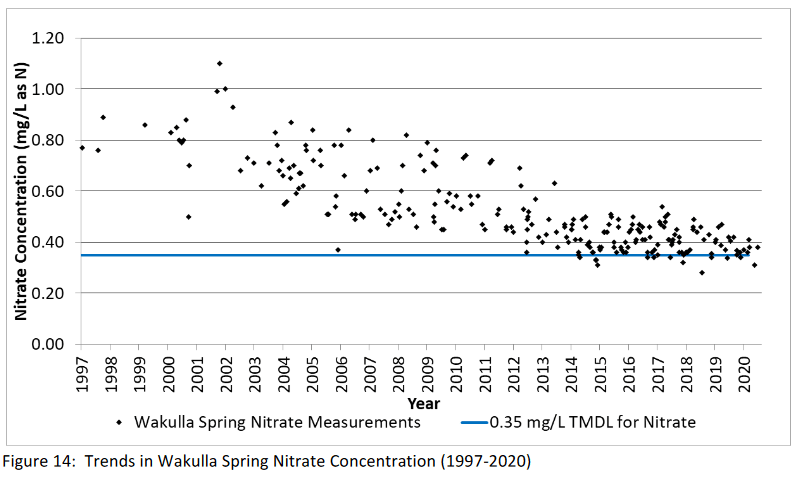

Nitrate concentrations, on the other hand, are quite high (more than 2.5 mg/L as compared to the BMAP target of 0.35 mg/L). Like many other Florida springs, the nitrate concentration has risen linearly in Rainbow Spring since the early 1990s at least (for many springs, the increase started in the 1970s). The BMAP attributed the high nitrate loading primarily to cattle and horse pasturelands. However, the rapid increase appears to have slowed and this trend seems to have occurred in other springs as well. Hopefully, we’re turning a corner there.

Image from SWFWMD Rainbow Springs dashboard: https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/projects/springs/rainbow/dashboard

Thanks for reading! I will end this last post with a photo of some wood duck friends (Aix sponsa) on a Rainbow Springs dock.