March 2024

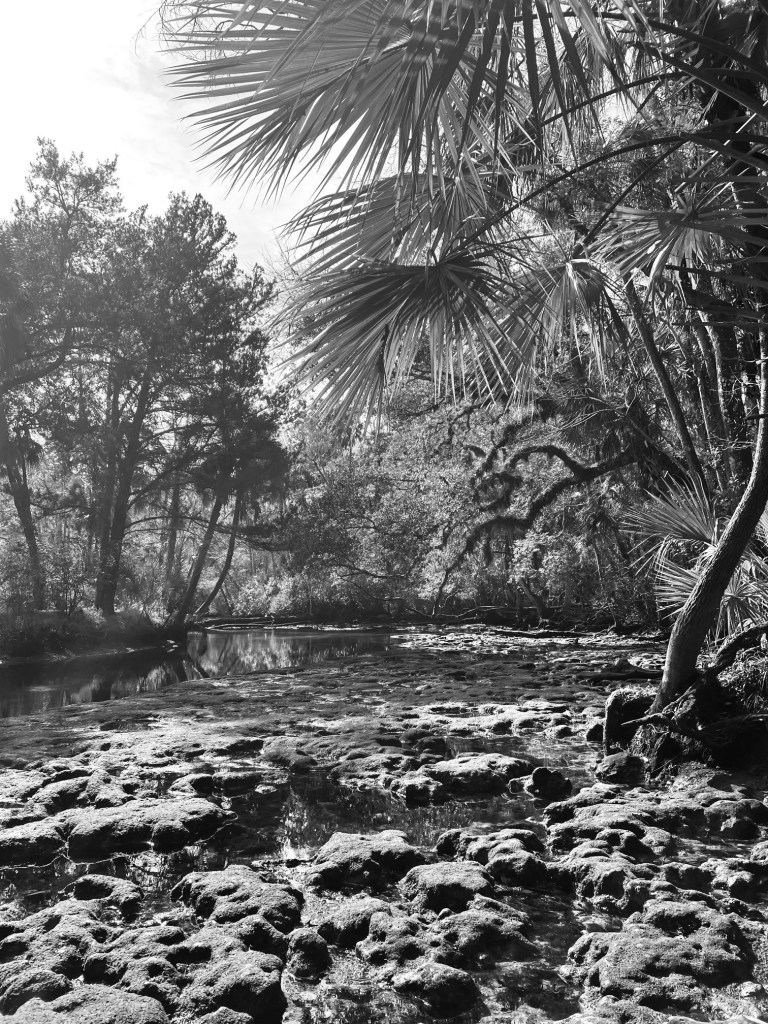

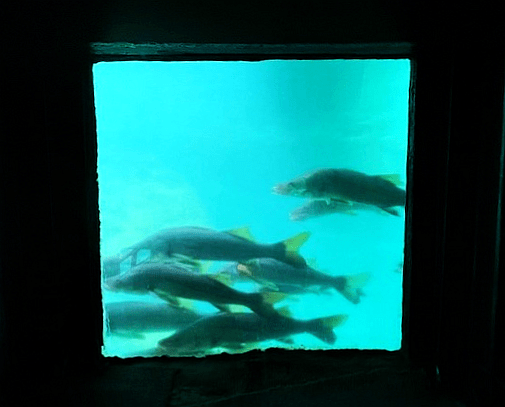

The Homosassa Spring main vent, called “The Fish Bowl”.

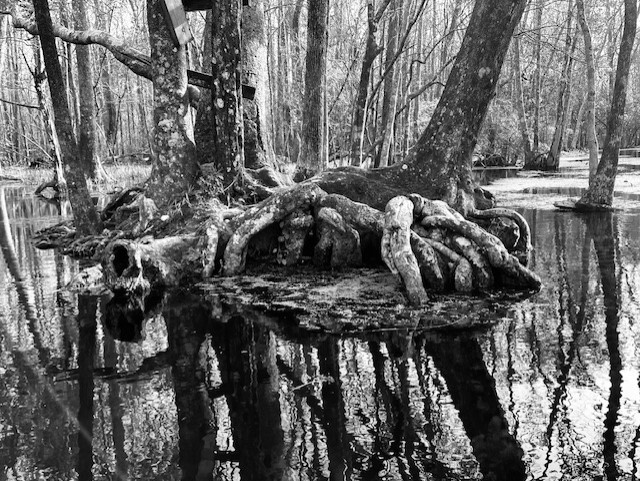

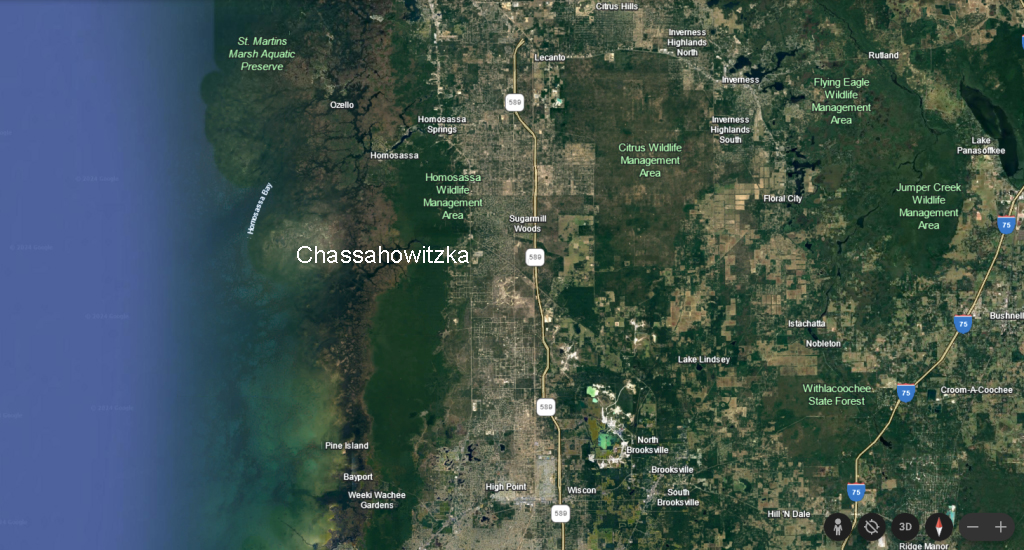

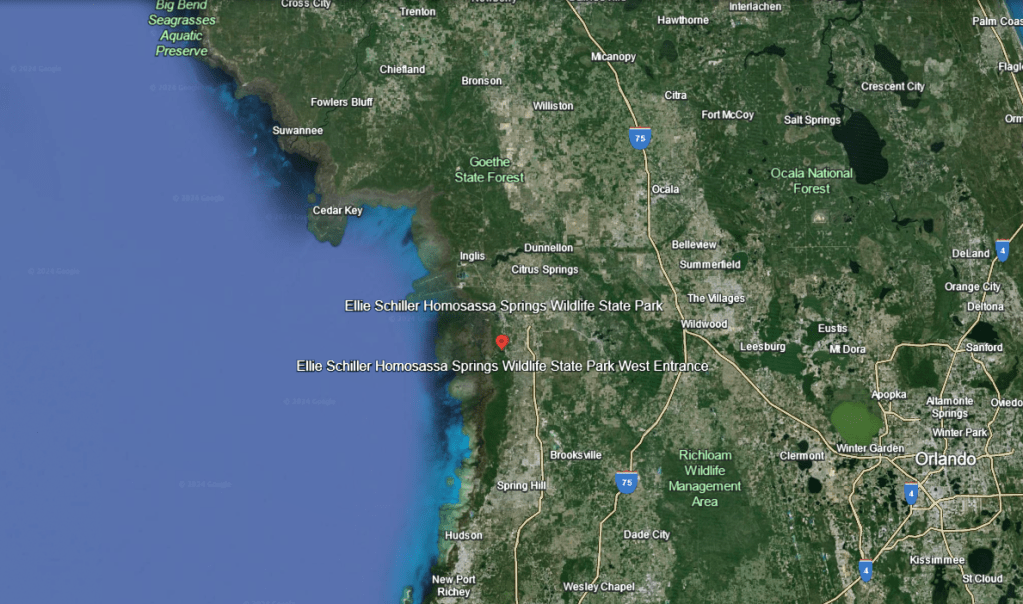

Homosassa Springs is like no other: part spring, part rehabilitation facility, part zoo. It sits on the “Nature Coast”, just south of Crystal River and north of its famous cousin, Weeki Wachee State Park. The whole coastline in that region of Florida is fairly undeveloped, but a ridge just to the east of the coastline has experienced rapid development. The land just to the east of that ridge has been in agricultural use for many, many decades.

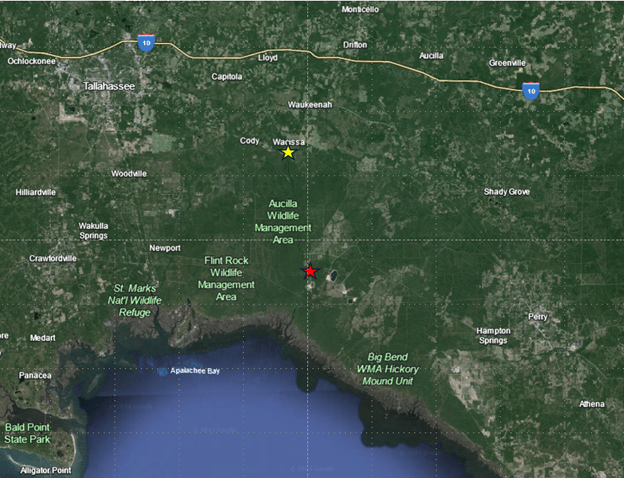

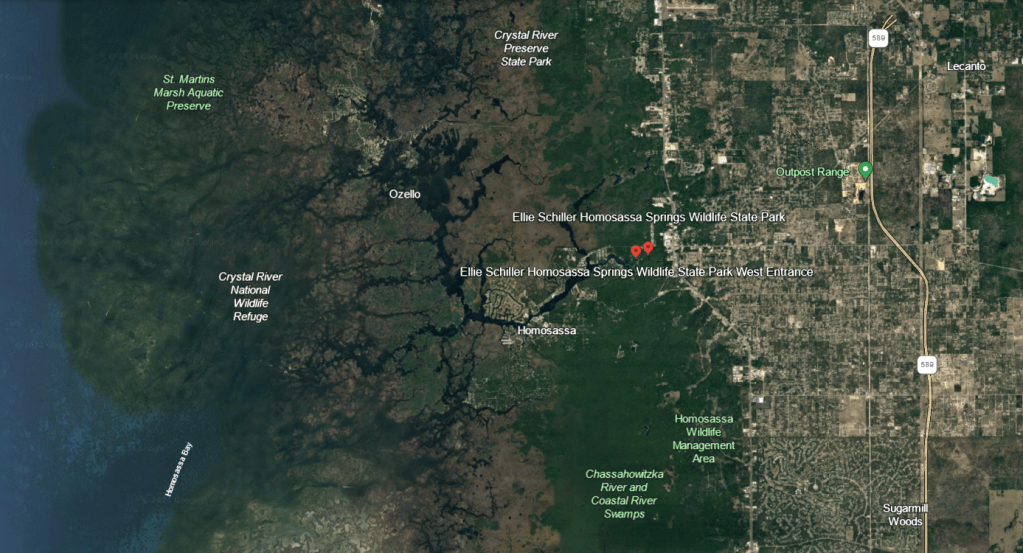

The location of Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park in the Nature Coast.

A close-up of the Nature Coast showing Homosassa Springs feeding into the matrix of channels along the Nature Coastline.

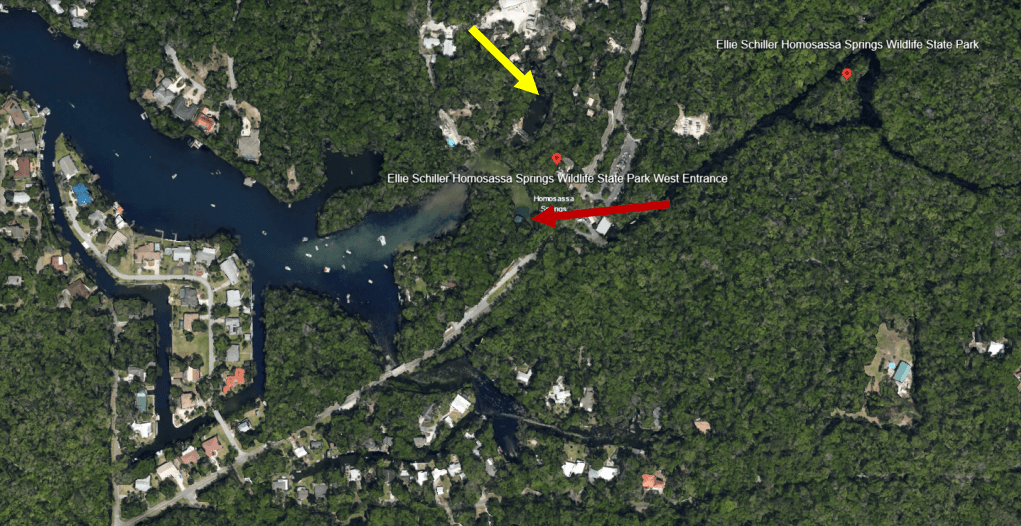

An even closer close-up of the spring showing the clear water flowing into the larger channel of the Homosassa River. The red arrow shows “The Fish bowl” and the yellow arrow shows the wildlife park.

Officially called Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park, the spring has been an attraction since the late 1800s. The park was one of Florida’s earliest attractions; a train bought visitors to the spring from 1893 to 1941. In the 1920s, a bridge built over the 55 ft. main vent, christened “The Fish Bowl”, allowed visitors to see through the clear water to the fish below. In the 1950s, an observation platform and underwater observatory replaced the bridge to give visitors an even more intimate view of the abundant common snook (Centropomis unidecimalis) and grey snapper (Lutjanus griseus) in the headspring. The state bought the property in 1989 and named the park for noted fisheries biologist/environmental advocate/philanthropist Ellie Schiller.

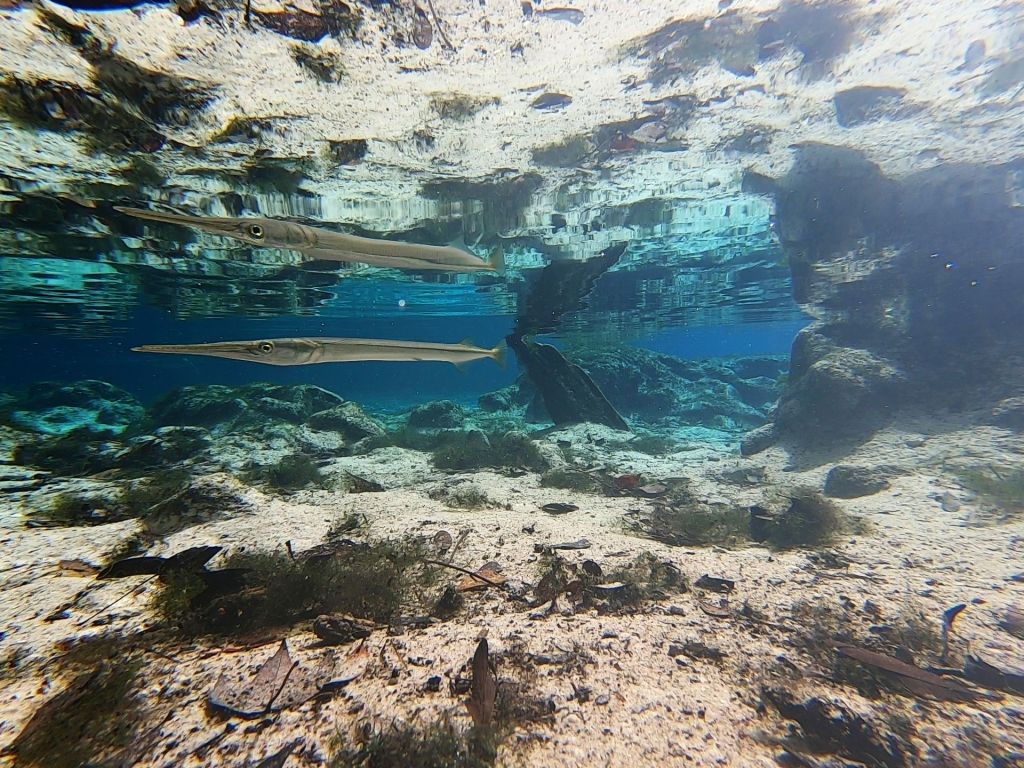

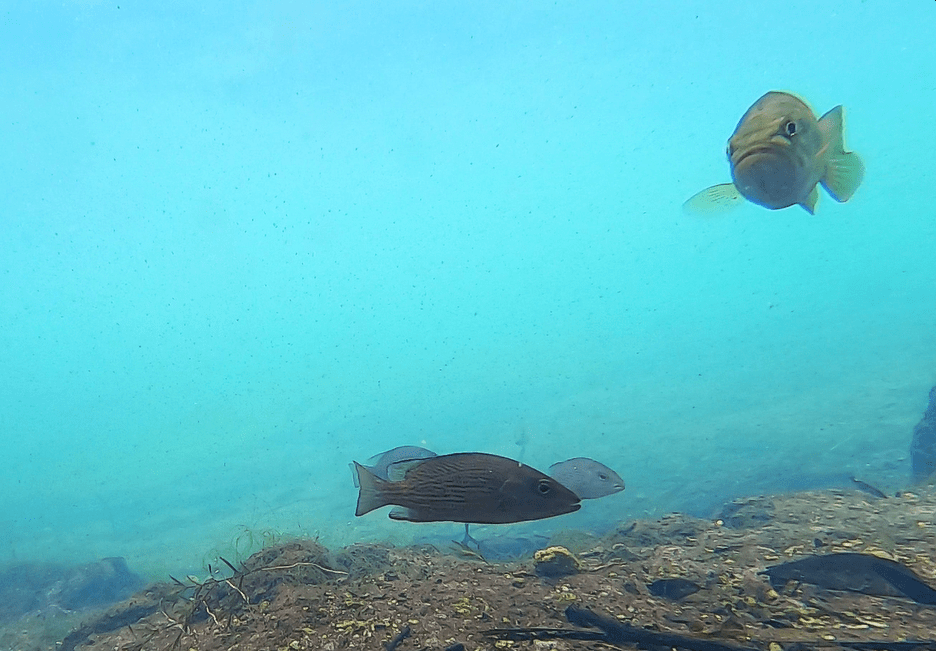

Common snook (top) passing by the window of the underwater observatory and some grey snapper (bottom) contemplating the drop off to the vent at the headspring.

In the 1940s, the wildlife park contained a variety of exotic animals like lions, bears, and monkeys. Now all the animals in the park are native to Florida, with the exception of Lu the hippo.

Lu, the hippo (Hippopotamus amphibius).

A Florida panther (Puma concolor coryi) resting in its house.

Two roseate spoonbills (Platalea ajaja) preening.

A barred owl (Strix varia) looking decidedly unimpressed.

Two flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) resting on one leg.

The park also rehabilitates injured manatees and serves as a refuge for uninjured manatees (Trichechus manatus). Manatees that have been hit by boats or stricken by cold stress (one of the most common sources of mortality for manatees after boat strikes) can recouperate in tanks on land. Once healthy enough to leave the tanks, they may be released into a large pen in the spring itself.

Manatees in the rehabilitation tanks (top) and in the natural pen being fed supplemental food (bottom).

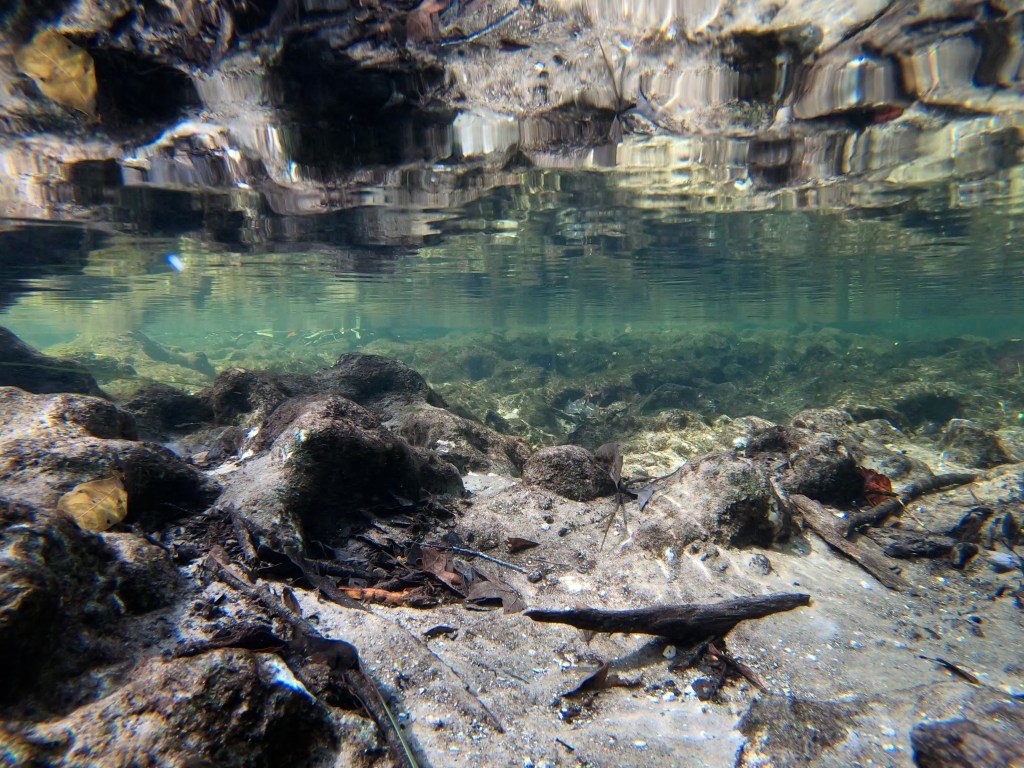

Unfortunately, my access to the water was somewhat limited, given the many uses and high public presence at this spring. The vast majority of the fish that I observed were in one of three salt-tolerant species: common snook, grey snapper, or sheepshead (Archosargus probatocephalus). I also observed a couple of Atlantic needlefish (Strongylura marina). Among the freshwater species, I recorded largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), spotted sunfish (Lepomis punctatus), and mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki).

Common snook in The Fishbowl.

Three grey snapper and a largemouth bass near the bridge on the run that leads into the wildlife sanctuary.

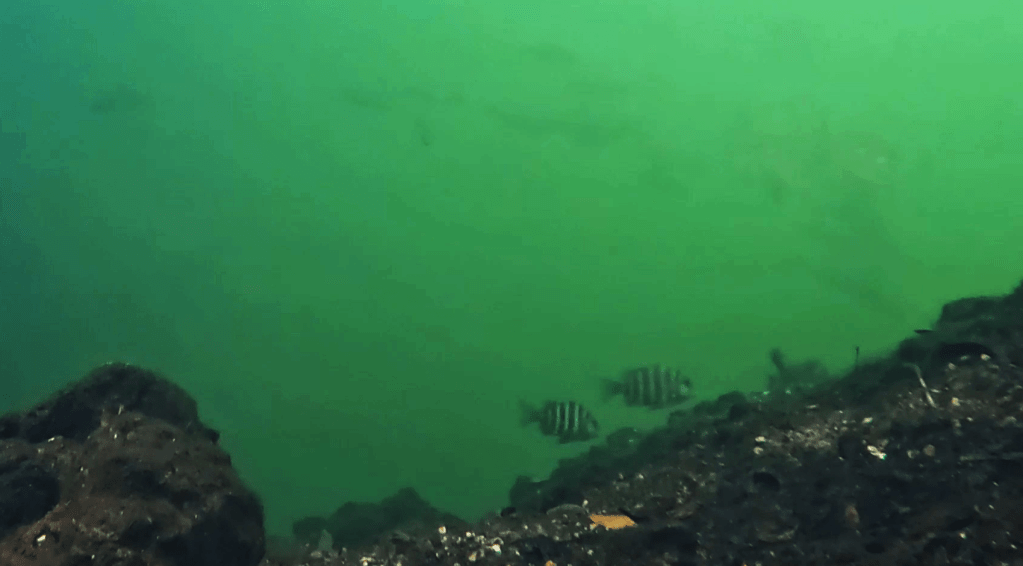

Two sheepshead in the Homosassa Springs’ Blue Spring.

Two spotted sunfish near the bridge on the run that leads into the wildlife sanctuary.

Homosassa Spring a first magnitude spring, with discharge ranging from 30 to over 100 cfs. The temperature (~23.5oC) and dissolved oxygen (2.3-4.7 mg/L) measurements that I collected were in line with the data collected by the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the USGS and are reasonably typical for Florida springs. As might be expected from the large number of salt-tolerant fish, Homosassa Springs is one of the higher conductivity (sort of the freshwater version of salinity) springs in Florida. A Southwest Florida Water Management District website reports that the spring receives flow from three vents, each differing in salinity, although there are more small springs in the springshed (https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/projects/springs/homosassa). The conductivity that I measured was more than an order of magnitude higher (3100 to 5000 microS/cm) than the conductivity at most of the other springs that I visited (in the 100-300 microS/cm range). The high conductivity, the large number of predators, and my limited ability to sample likely account for the low number of freshwater fish that I observed.

This spotted sunfish was chewed by something…

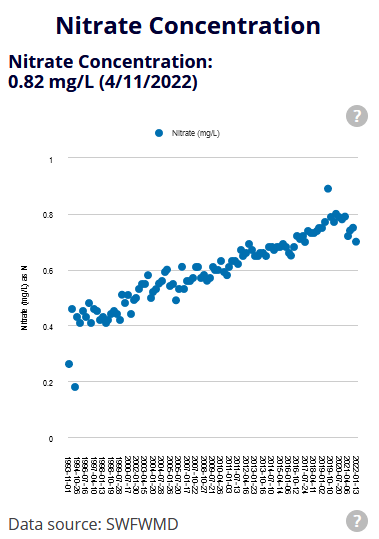

Unfortunately, Homosassa Springs is one of the Florida springs that has experienced dramatic and linear increases in nitrate loading, perhaps due to a combination of agricultural and residential land use. The Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) produced for Homosassa Springs by the FL Department of Environmental Protection in 2018 cites farm fertilizer as the largest source of load (24%) followed by urban turfgrass (19%), septic systems (15%), and sports turfgrass (12%). Livestock waste also has contributed substantial nutrients to the springshed (11%). A variety of projects have been planned, including fertilizer application reductions, education programs, and transitioning homes from septic to sewer. Interestingly, the numbers appear to have dropped off in the last couple of years.