January and March 2024

Apparently, Floridians like their Gum trees. Gum trees include sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) and the tupelos (Nyssa spp.), which we have in Florida naturally, and eucalyptus, which we do not. There are actually some super fun gum trees that I just discovered five minutes ago, such as a lemon-scented gum (Corymbia citriodora), a rainbow gum (Eucalyptus deglupta), a scribbly gum (Eucalyptus haemastoma), and a salmon gum (Eucalyptus salmonophloia–there’s the fish in this digression! https://www.thespruce.com/twelve-species-of-gum-trees-3269664). [Hopefully, we’re keeping those fun gum trees in their homes.]

Floridians also like to name things Gum swamp. I titled this post as I did because “Gum” and some version of “slough” or “swamp” show up all over the state (a slough is essentially a flowing swamp). There’s the Gum Slough near Lake City that is a described by Apple Maps as a lake, but looks more like a wetland. There’s a Gum Swamp at the northern end of the Okeefenokee Swamp. There are Big Gum Swamp, Little Gum Swamp and Gum Swamp Creek at the southern end of the Okeefenokee. There’s a Gum Swamp southeast of Jacksonville. There’s Gum Root Swamp northeast of Gainesville. There’s a Gum Swamp that appears, on Google Earth, to connect the Manatee River and Myakka River watersheds. And there’s a Gum Swamp Branch just north of the Hardee Correctional Institution that, if I squint sideways, might connect with the Gum Slough on the Manatee River. And finally, there’s the Gum Swamp surrounding the headwaters of the topic of this post: Gum Slough spring that flows into the southern Withlacoochee River (and yes, we have two Withlacoochee Rivers as well).

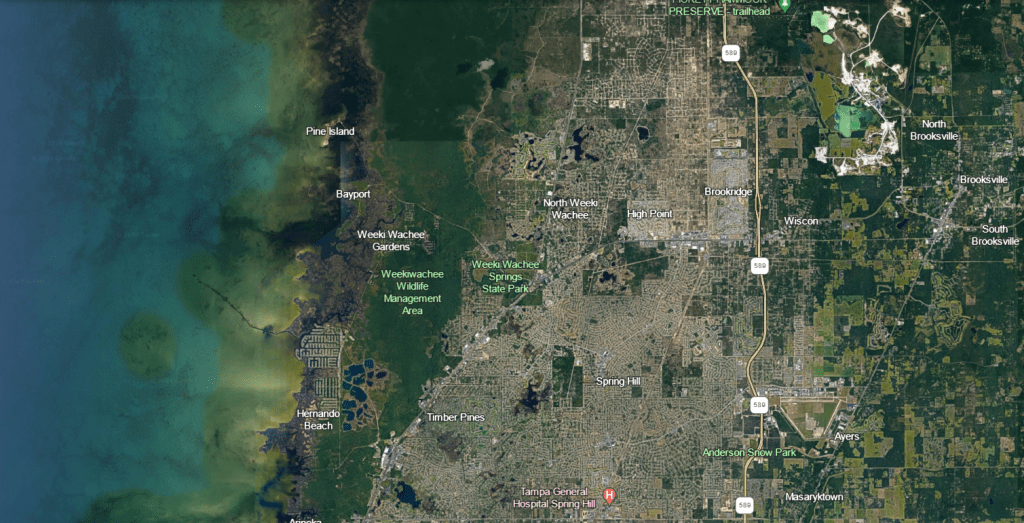

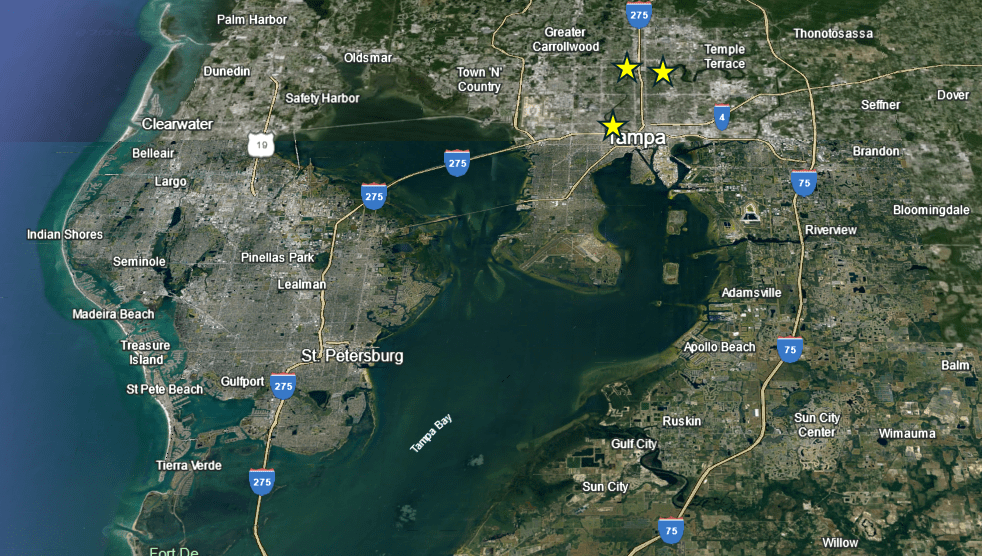

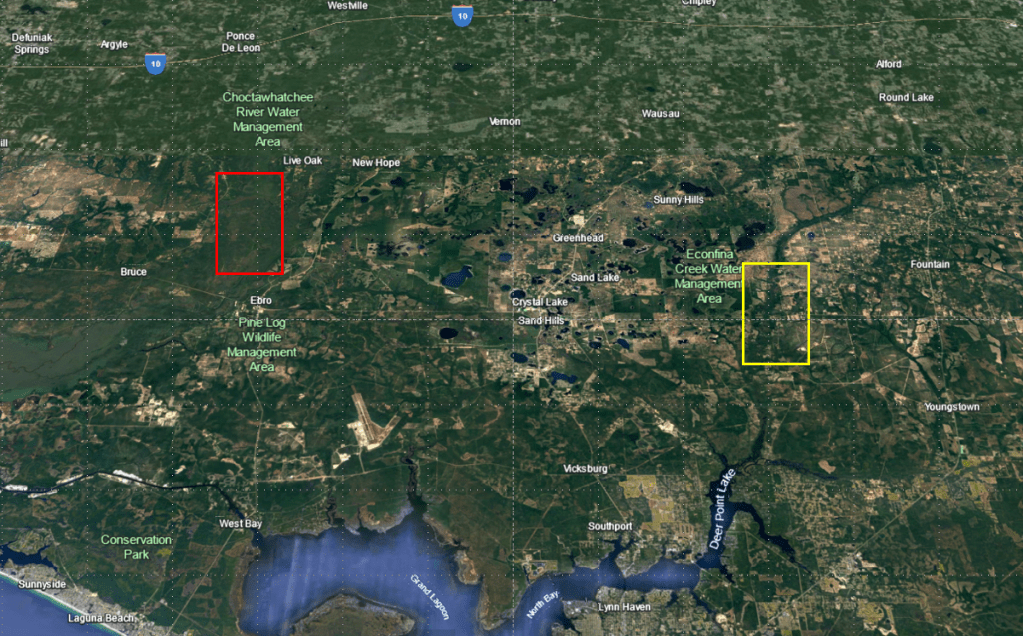

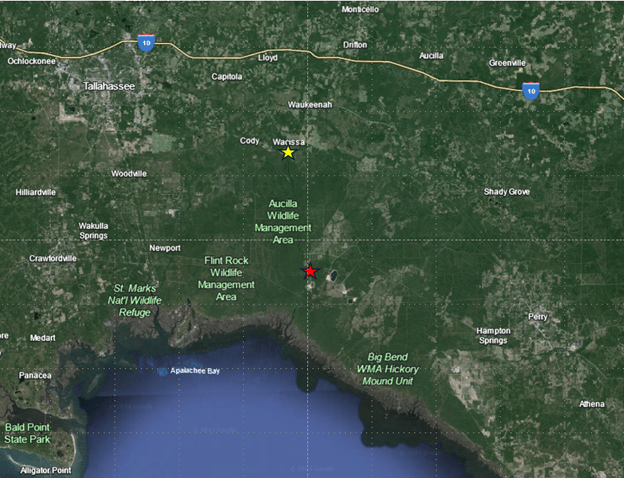

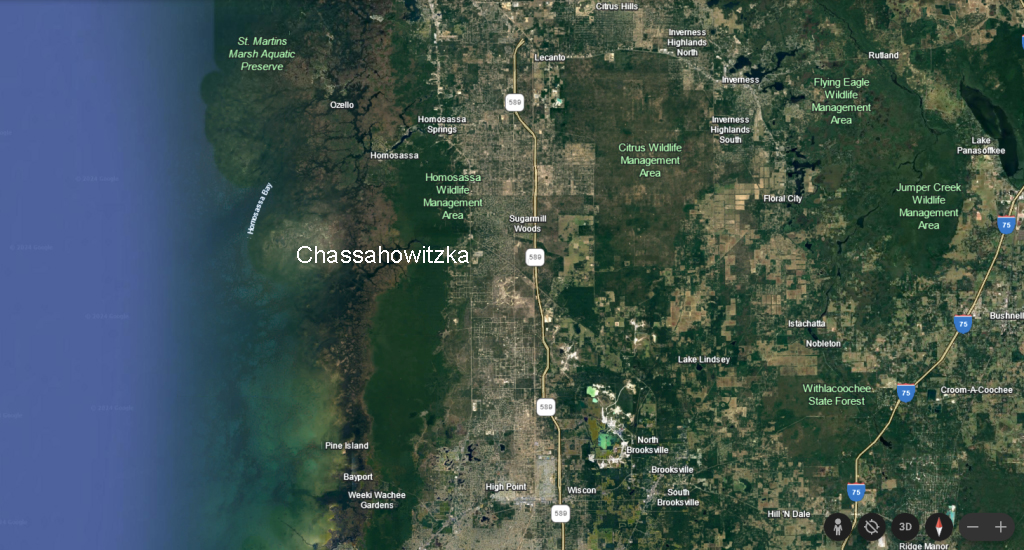

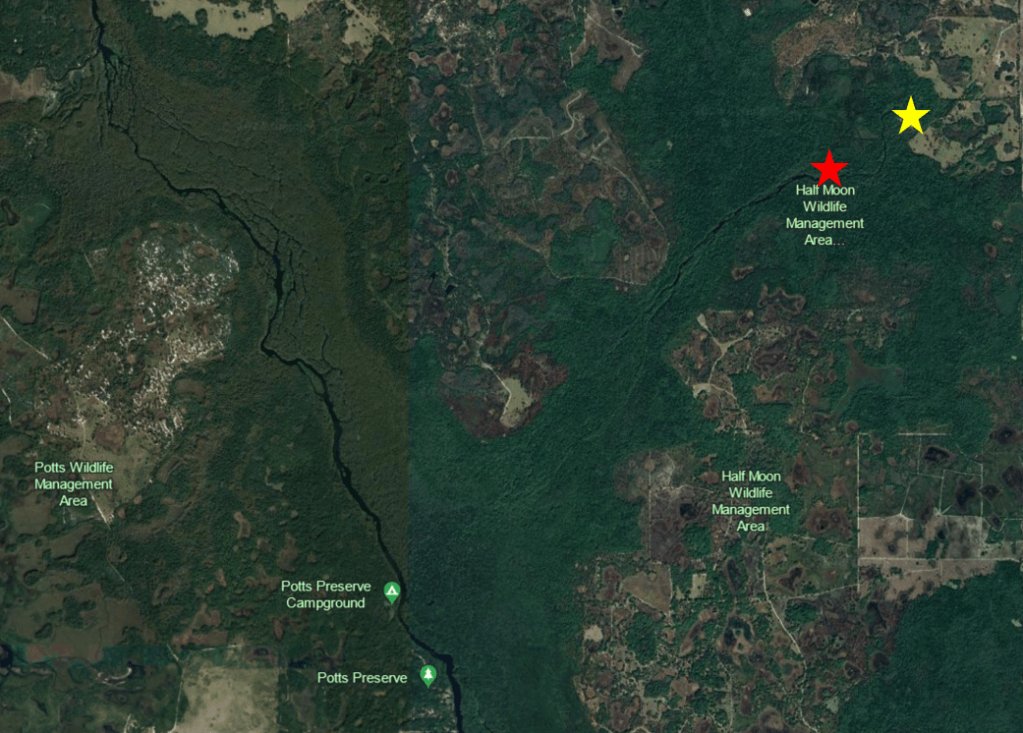

Google Earth image of some of the “Gum” slough/swamps in Florida. The yellow star indicates the location of the Gum Slough that is the topic of this post.

The development pressure in the area is intense, with Ocala to the north and The Villages to the east. However, the land around the spring itself is still swamp, forest, and pasture. All of the land that abuts the spring is either wildlife management area or nonprofit. Visiting the headspring, which is owned by a nonprofit, feels very remote, a bit like you’re going back in time.

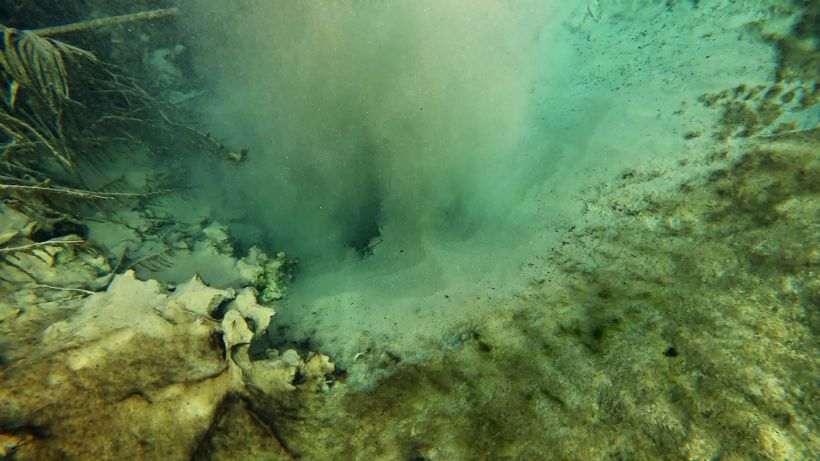

At least seven vents provide the majority of the flow for the spring, three at the start of the spring, three about a mile downstream, one more that I did not find, and perhaps even a few others that have only been seen on a SWFWMD lidar map (kind of like radar). I was told by one of the owners of the nonprofit that the flow from first three springs is equivalent to a second magnitude spring, but the addition of the other four springs downstream elevates the flow to a first magnitude spring.

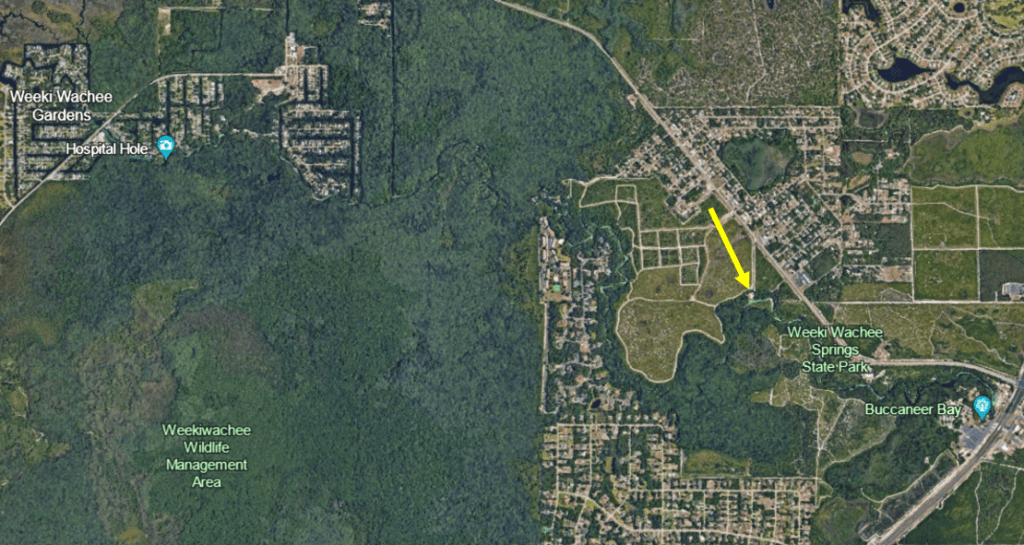

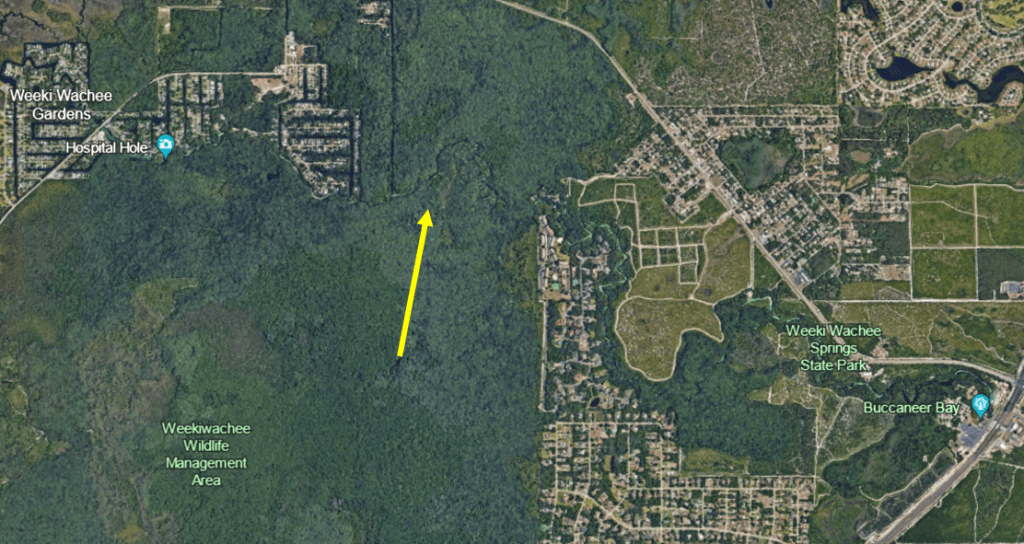

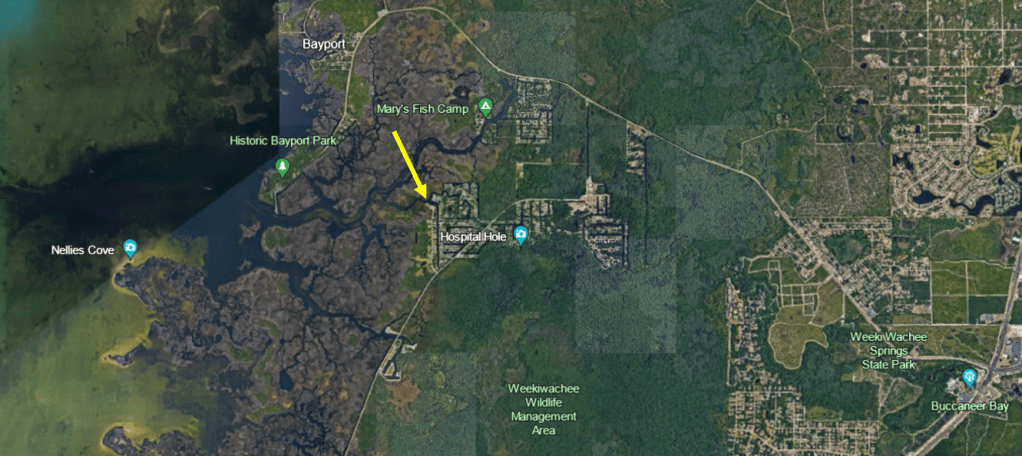

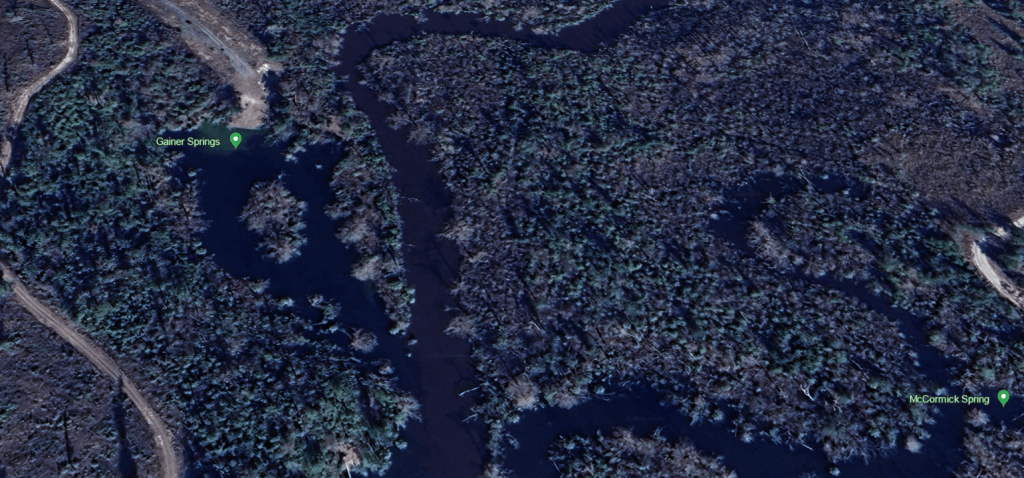

Google Earth (top) and Google Map (bottom) images of the Gum Slough run. The locations of the two clusters of seven springs are represented by the stars in the top map. The bottom map shows the braided morphology of both the Withlacoochee River and Gum Slough.

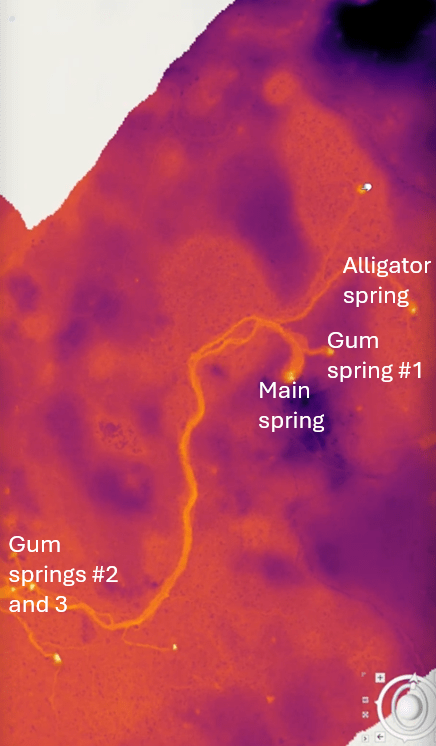

Screenshot of a lidar image of Gum Slough from a SWFWMD video (https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/media/video/6042) about exploring the springs of Gum Slough. According to the video, the bright spots are springs. A couple of the lighter, unlabeled springs had runs that were too shallow and narrow to paddle.

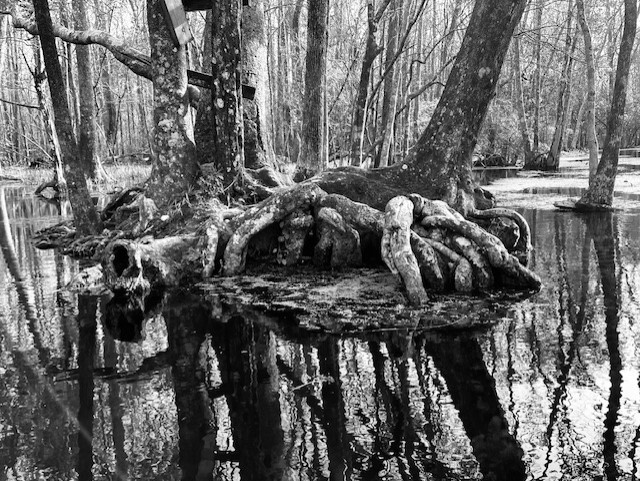

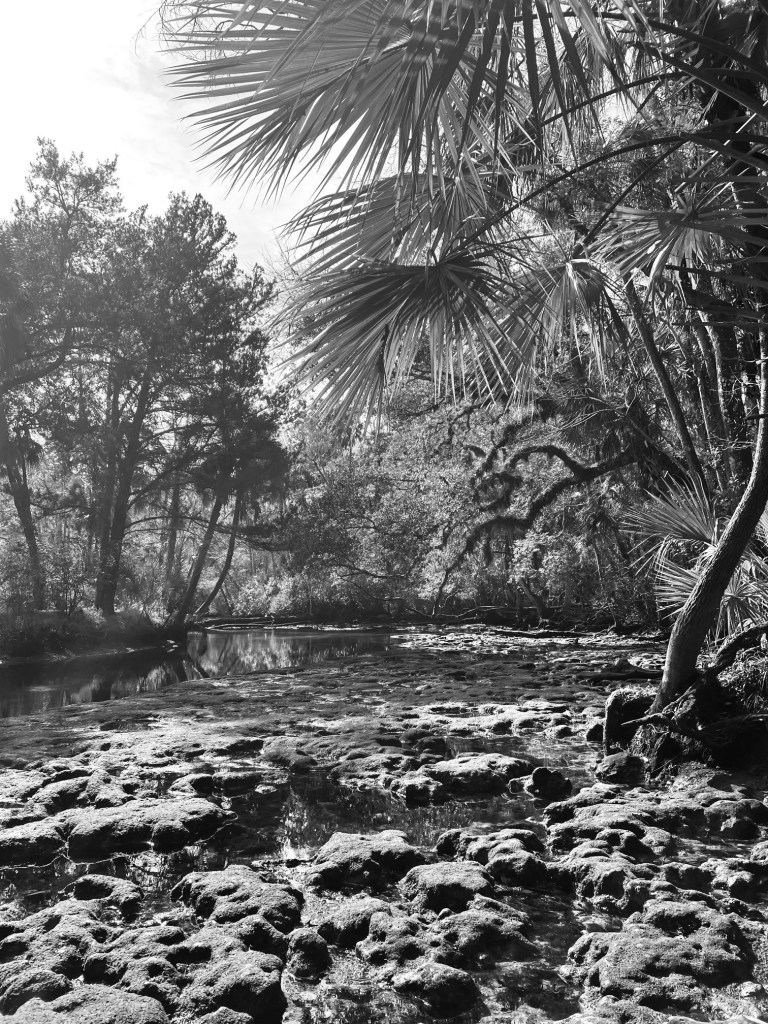

Even with the substantial flow inputs, the spring is narrow and intimate in the upper mile or so. In fact, at low water, the spring can be so shallow in the upper reaches that kayaks need to be portaged in spots. I have not yet paddled lower Gum Slough, but given how braided it is and photos that I have seen, I think that it would feel intimate downstream as well.

Gum Slough just downstream of the first three springs in March.

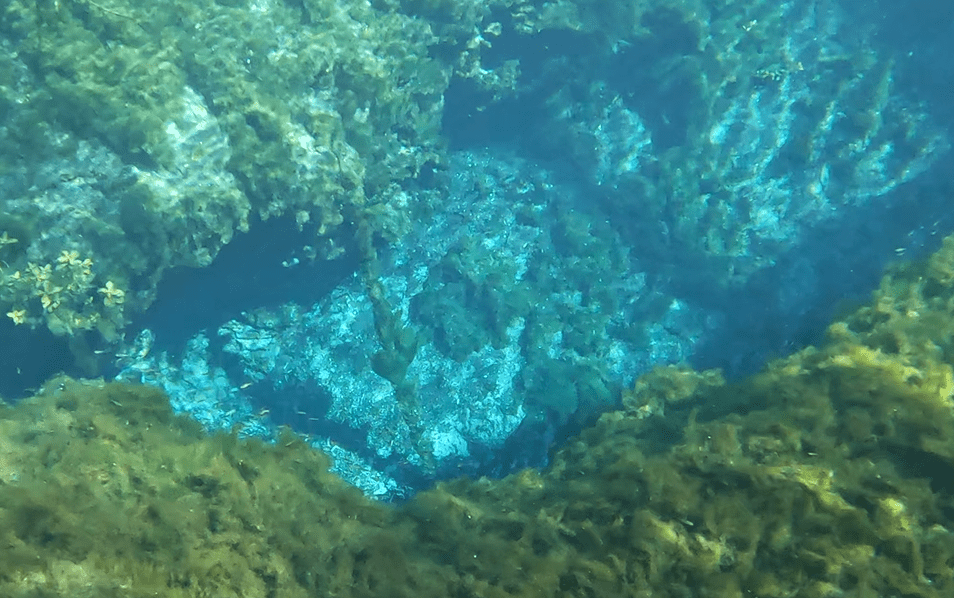

Gum Main Spring

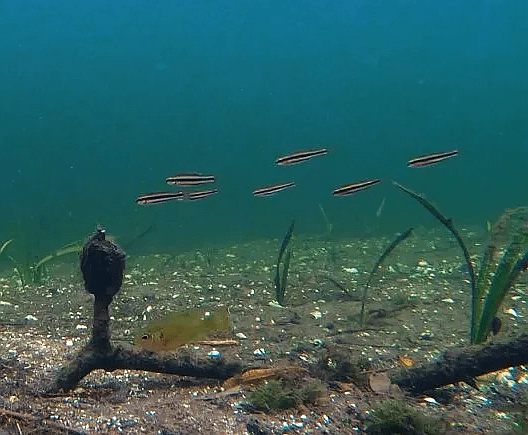

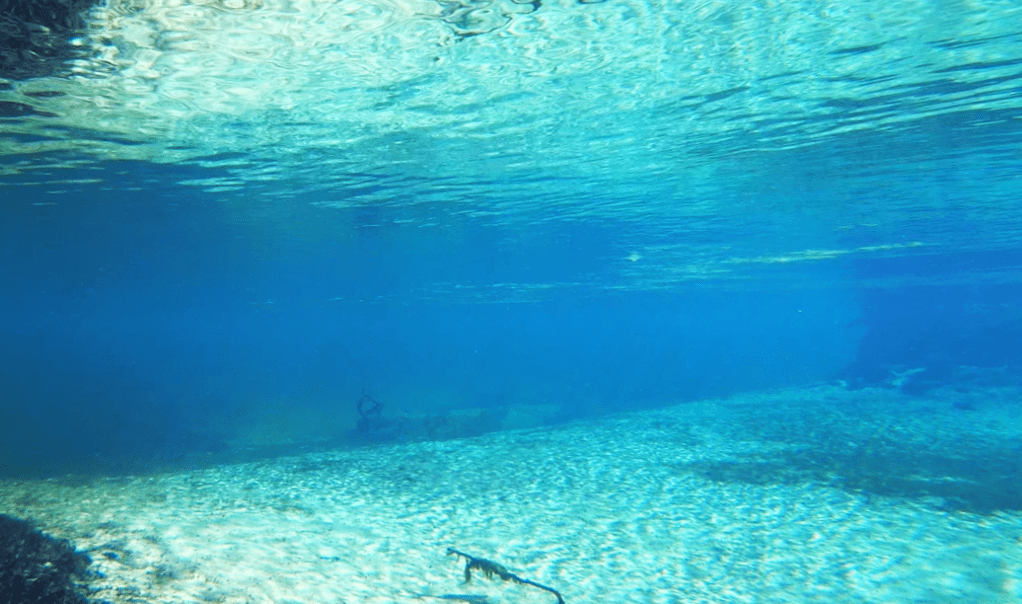

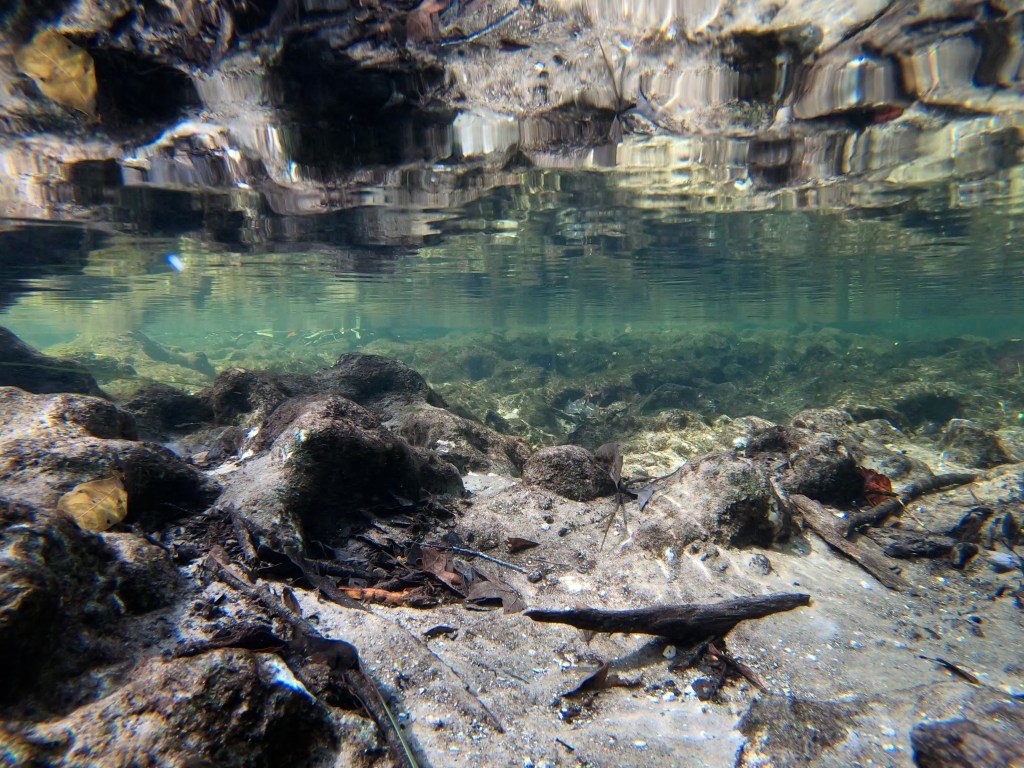

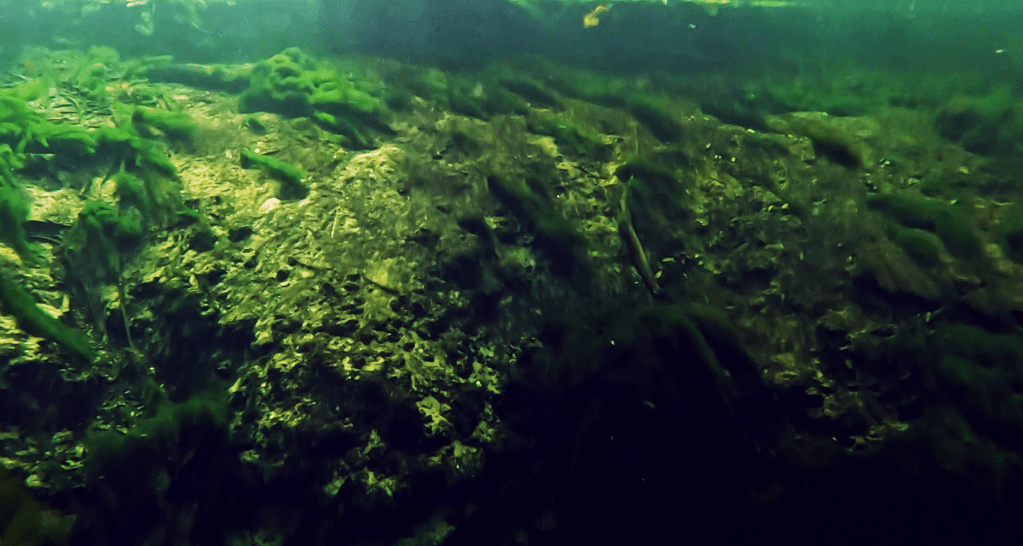

The Gum Slough main vent is represented by perforations in a large limestone pool. When I visited in January and March, algae blanketed both the floor of the main spring run and a lot of the eelgrass (Valisneria americana) just downstream, but the snails did not seem to mind. There were thousands upon thousands of snails, both on the eelgrass and on the exposed sand.

Gum Slough main vent (top) and the run downstream (bottom). The entry of Gum Slough Spring #2 is visible in the top right corner and dozens of snails can be seen in the lower left corner.

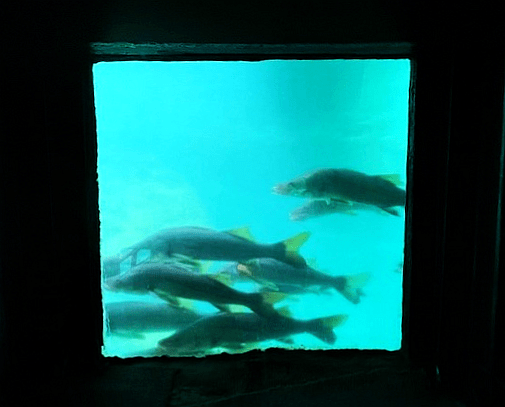

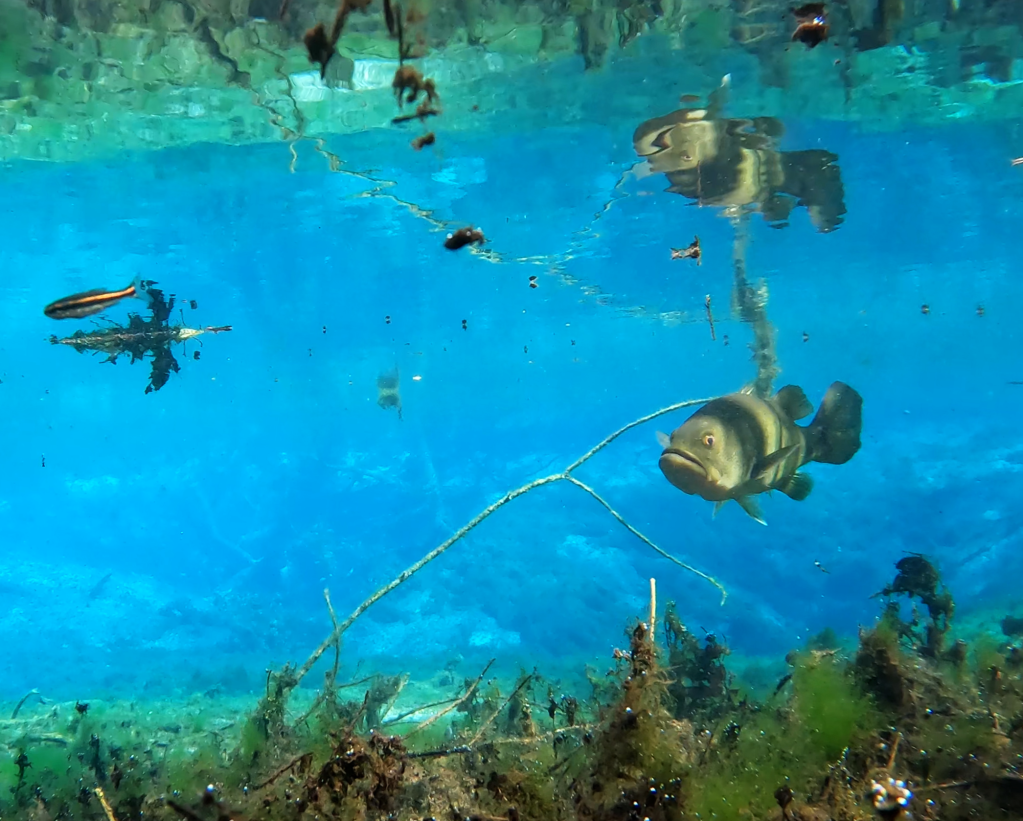

I recorded an impressive number of sizeable largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides)–also, loads of sunfish, particularly spotted sunfish (Lepomis punctatus)–among the ten sites that I collected video. The clear water gave some good views of bowfin (Amia calva) as well. The rippling motion of their dorsal fins is a cool way to move.

A skinny largemouth bass at the headspring in March and a bowfin with a spotted sunfish just downstream in January. I mention the difference in sample time here because the algae is green the top photo and brown in the bottom photo.

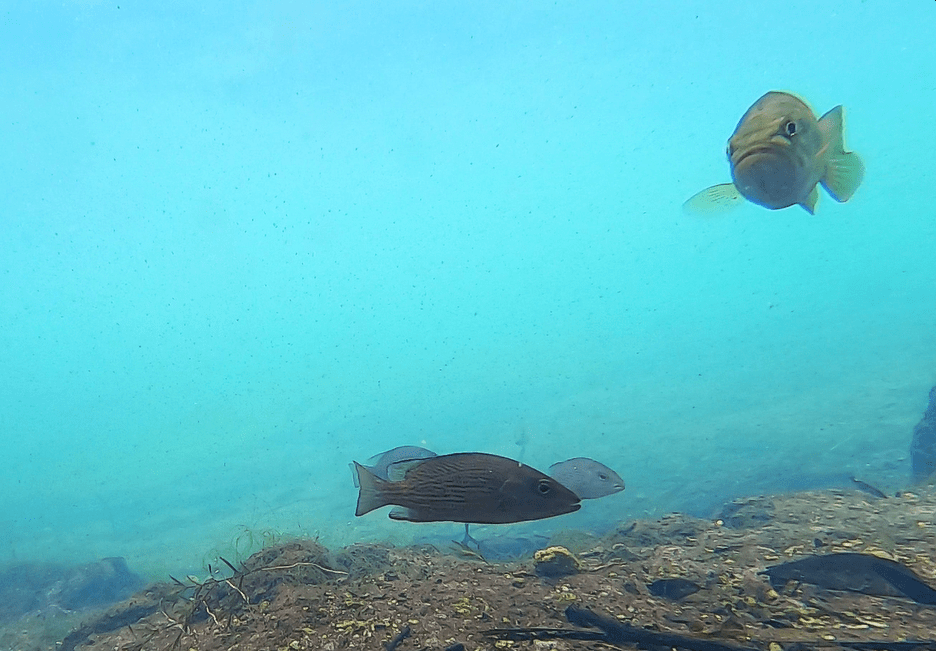

From further downstream, a large and golden largemouth bass, a very large seminole killifish (Fundulus seminolis) with a spotted sunfish, and a pretty redbreast sunfish (Lepomis auritus, bottom).

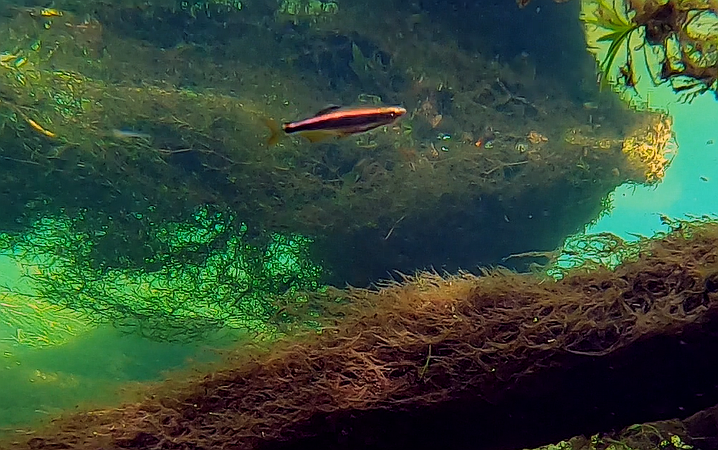

Downstream where there was some structure, I found shoals of shiners, both adult (photo) and larval (video). Note the larval shiners streaming from one mass of plants to another. They slightly rerouted when the bass approached.

Gum Spring #1

The Gum Slough #1 vent was just meters away, but it looked completely different than the main spring, much more blue. The pool was much narrower, so the banks were steeper and the vent itself was obscured by plants.

Gum Slough Spring #1 vent (top) and its short and shallow run (bottom)

Like the main spring, Gum Slough #1 supported shiners, killifish, sunfish, bass, and turtles.

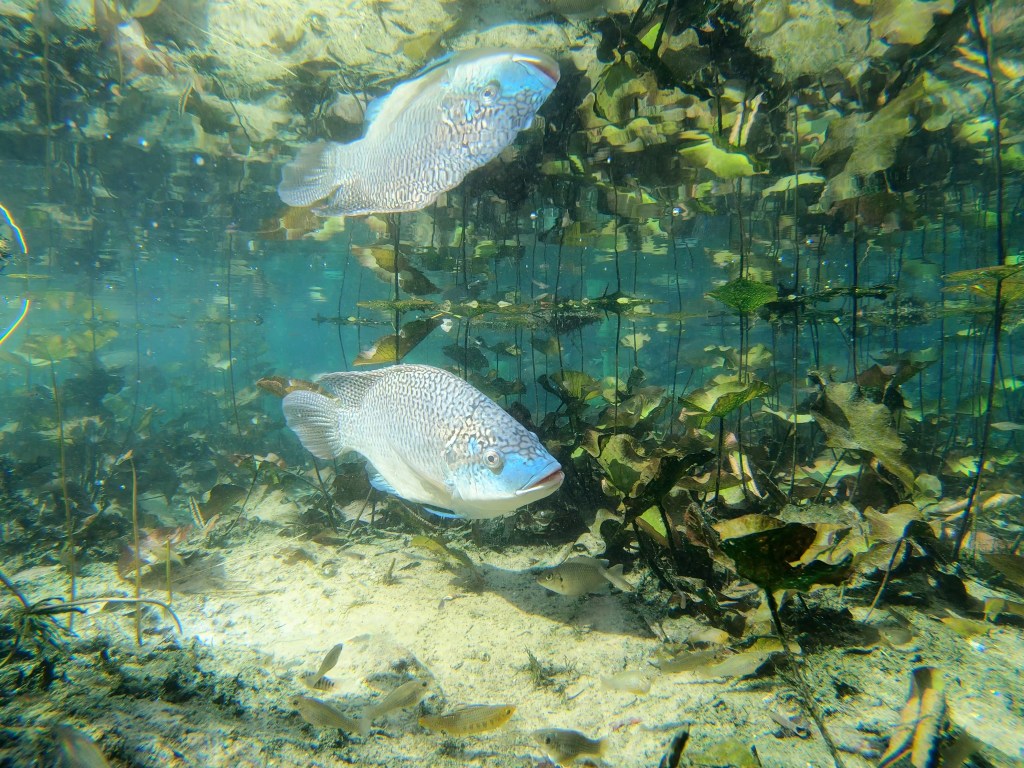

A largemouth bass near the edge of the Gum Slough #1 vent.

Spotted sunfish attacking a) food that is impossible to see (top) and b) my float (bottom).

Alligator Spring

Of the springs that I visited on Gum Slough, Alligator Spring was my favorite to paddle. The run was windy and tree canopy-covered with dappled sunlight falling on the water. Below water, the vent dropped off quickly, producing a limestone wall, although it was covered in algae.

Looking up Alligator Spring run toward the headspring.

Alligator Spring vent above water (top) and the limestone wall of the vent below water (bottom).

Alligator run was a bit more tannic than the other spring runs, but I observed the same suite of fish along its length as I did in the other two runs upstream.

Some impressive largemouth bass and colorful redbreast sunfish (Lepomis auritus) in Alligator Spring run.

Gum Slough springs #2-3.

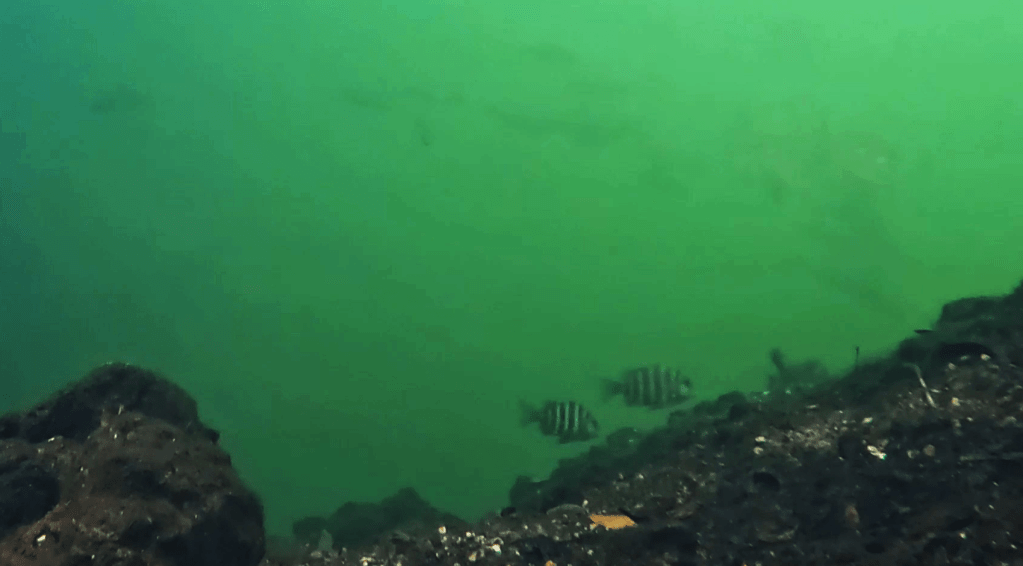

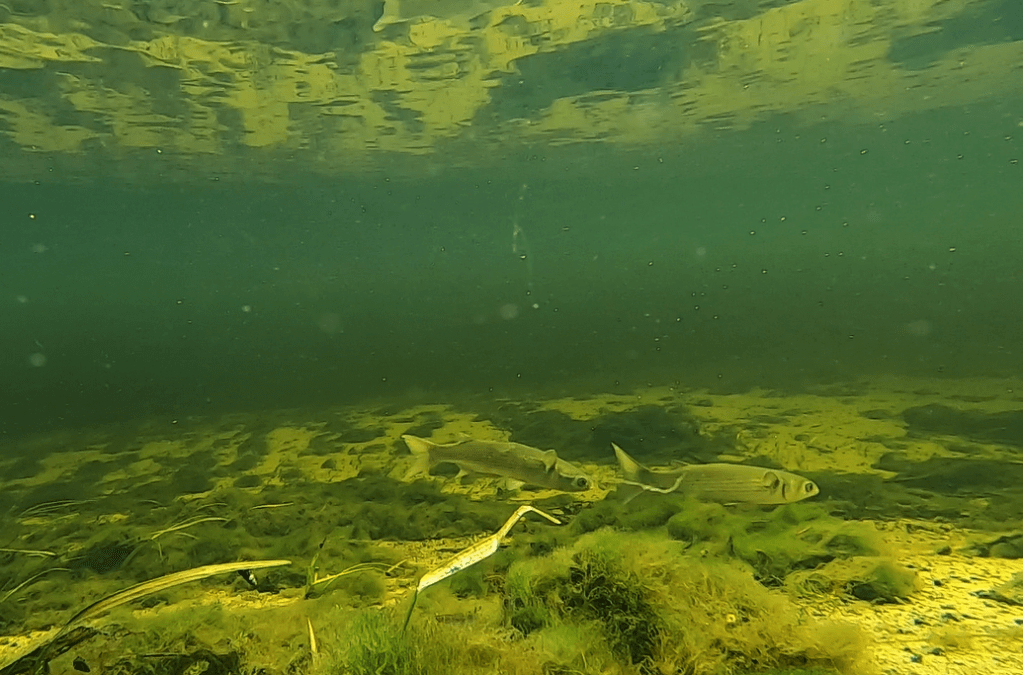

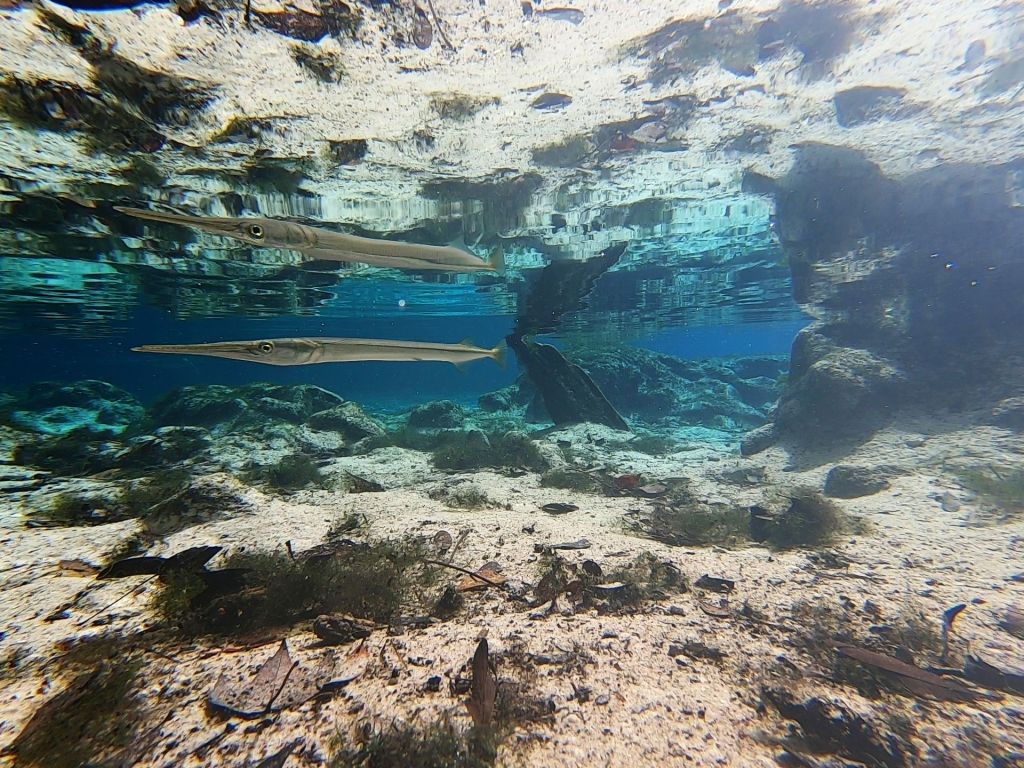

The downstream spring vents seemed much bigger than the upstream vents. And unlike the springs upstream, the downstream vents were right in the middle of the channel, rather than at the start of a run. An impressive number of large predators (largemouth bass, Florida gar, and bowfin), roamed these vents. While the largemouth bass cruised through singly or in pairs and the bowfin always were alone, at least 19 Florida gar hung over the vent of Gum Slough #4. I usually see Florida gar on their own, not in groups.

Gum Spring # 2 with a sunfish and a largemouth bass.

Gum Spring # 3 with several largemouth bass and a couple of sunfish.

Gum Spring # 4 with a boatload of Florida gar (Lepisosteus platyrhincus) near the surface. That group was the largest number of Florida gar that I have ever seen together.

Two impressive largemouth bass, one showing off its large mouth.

The Florida gar following each other around–mating?

Despite the large number of predators, I also observed a fair number of small fish like shiners and killifish, probably because I set my cameras back in the plants. Plants can provide cover from that large mouth on the largemouth.

A metallic shiner (Pteronotropis metallicus, top) and three bluefin killfish (Lucania goodei, bottom).

In addition to the loads of snails on the run, when I visited in March, there were impressive numbers of mayflies and blue damselflies taking advantage of the warmer weather.

A mayfly on my data book (top) and loads of blue damselflies on an exposed log (bottom).

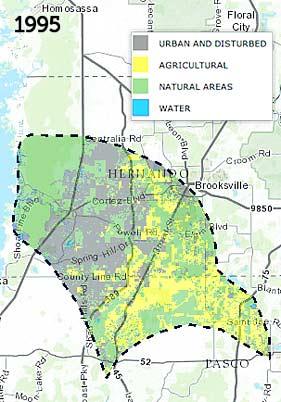

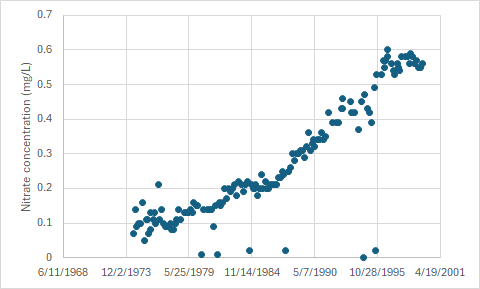

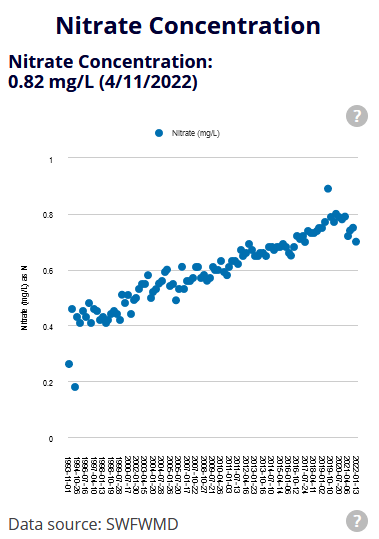

Out on Gum Slough, the spring feels very remote. However, the Sarasota Water Atlas categorized Gum Slough as “Impaired” (https://sarasota.wateratlas.usf.edu/waterbodies/rivers/14493/gum-slough) and the thick algal beds that I observed on multiple visits would support this interpretation. The discharge of Gum Slough has varied between 55 and 159 cfs, according to the USGS (https://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis). The Gum Slough Minimum Flow and Level plan puts the average streamflow at 98 cfs over the period of 2003-2010, making it just shy of first magnitude, although the time series was quite short (https://www.swfwmd.state.fl.us/sites/default/files/documents-and-reports/reports/Original-Gum_MFL_Report_0.pdf).

USGS had no water quality data for Gum Slough, but there were some in the SWFWMD MFL plan (again, a short time series). The temperature of Gum Slough headspring was on the warm side (~23-24oC according to both SWFWMD and my data), but it was a little cooler below the second set of vents when I measured it (21.5-22.9oC). The dissolved oxygen was moderate at the headspring (3.11 mg/L for SWFWMD and 2.5-4 mg/L for me), but it was higher when I measured it downstream (~5-7 mg/L). This increase is not surprising, given all the submerged plants and algae. The conductivity was predictably low (324 microS/cm for SWFWMD and ~370 microS/cm for me), given the distance from a source of saltwater.

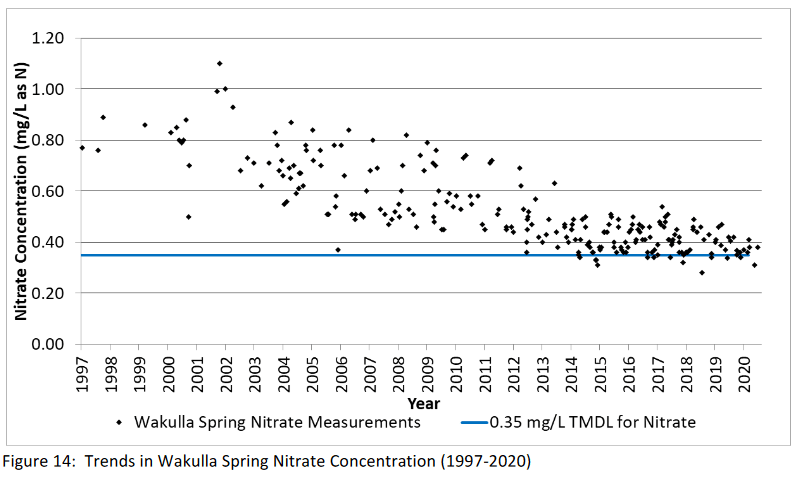

The SWFWMD MFL plan reported an average nitrate concentration of 1.02 mg/L, ranging up to 2.28 mg/L. These values are quite high, much higher than the often-cited 0.35 mg/L background concentration (the MFL report actually used a much lower number for the background: 0.05 mg/L). The report says that: “this [nitrogen concentration] is slightly higher than the mean of 1.17 mg/L for the Rainbow Springs for the same period”. This comparison is interesting, given the much more obvious overlap between human development and Rainbow Spring (there are neighborhoods just north of the headspring and houses down one bank of its run). The MFL plan reported a phosphate concentration of 0.04 mg/L, which is within a stone’s throw of the likely background concentration. So… while Gum Slough feels untouched as you float down it, it has been touched underground by human activity.

Floating down Gum Slough in March.