March 2024

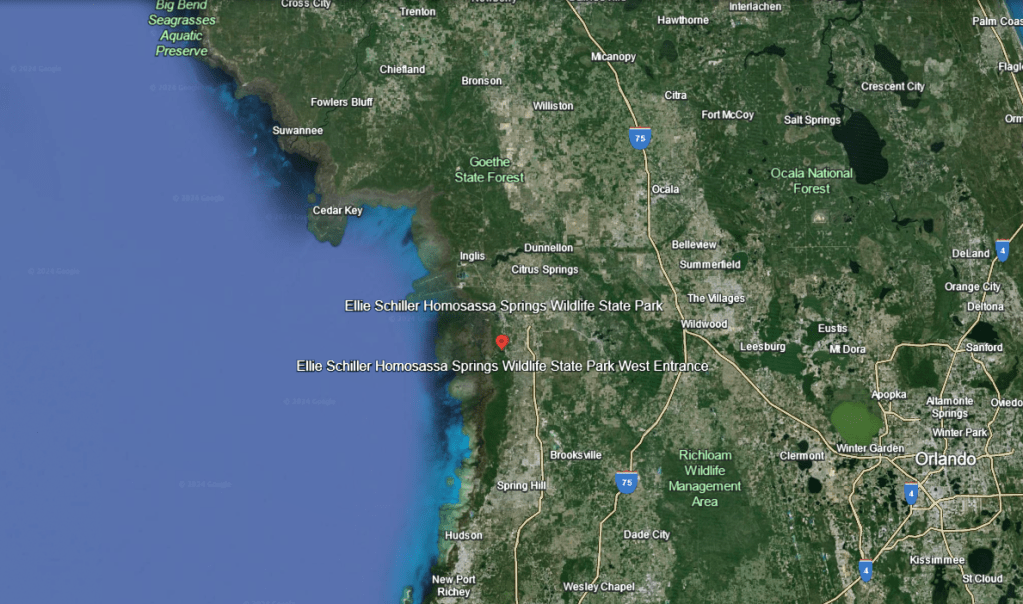

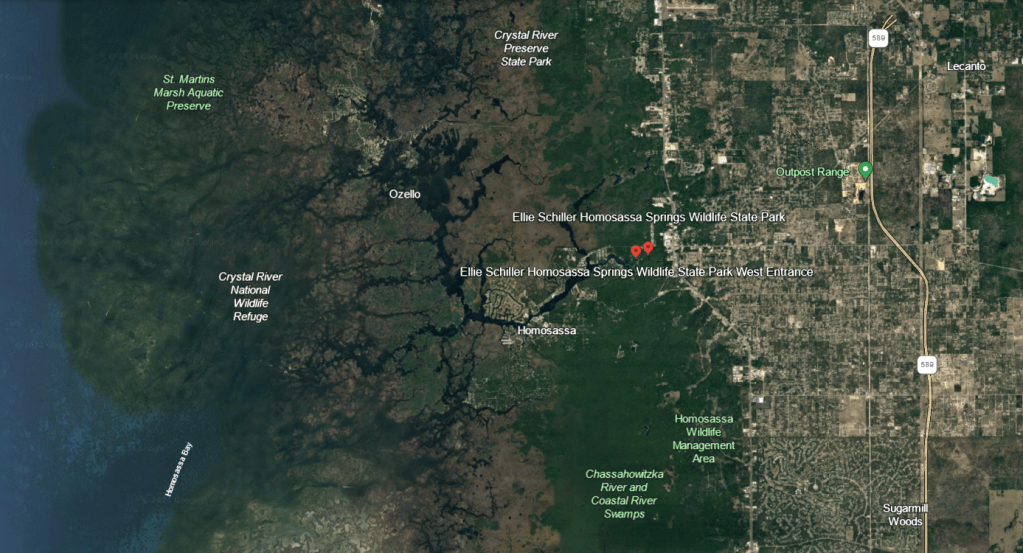

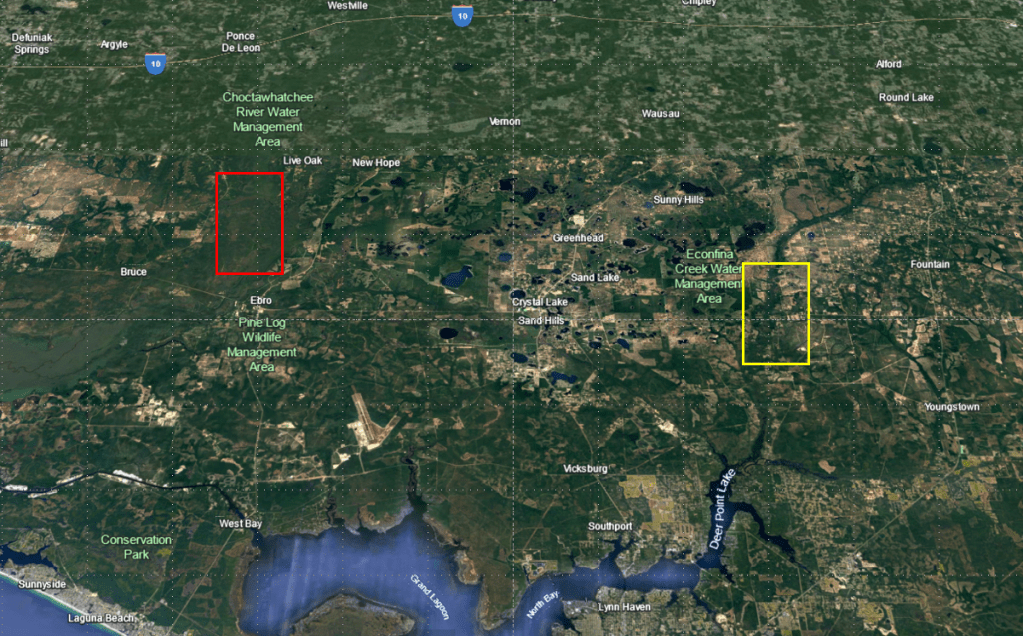

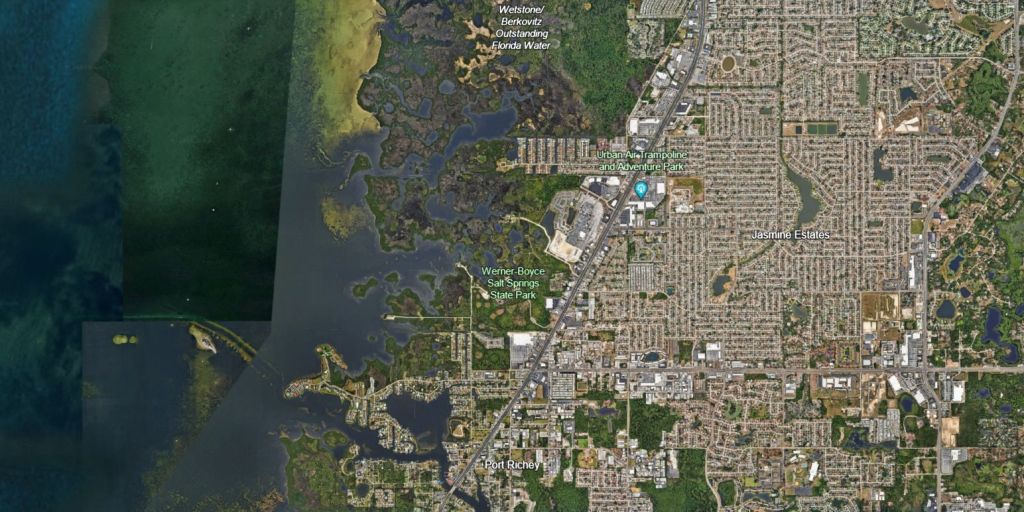

Werner-Boyce Salt Spring is a deep hole out in the matrix of mangrove wetlands, channels, and pools (shown above) of the Nature Coast, about halfway between Homosassa and Clearwater. When in the park, the land seems remote and untouched, but development is not even on the other side of the highway.

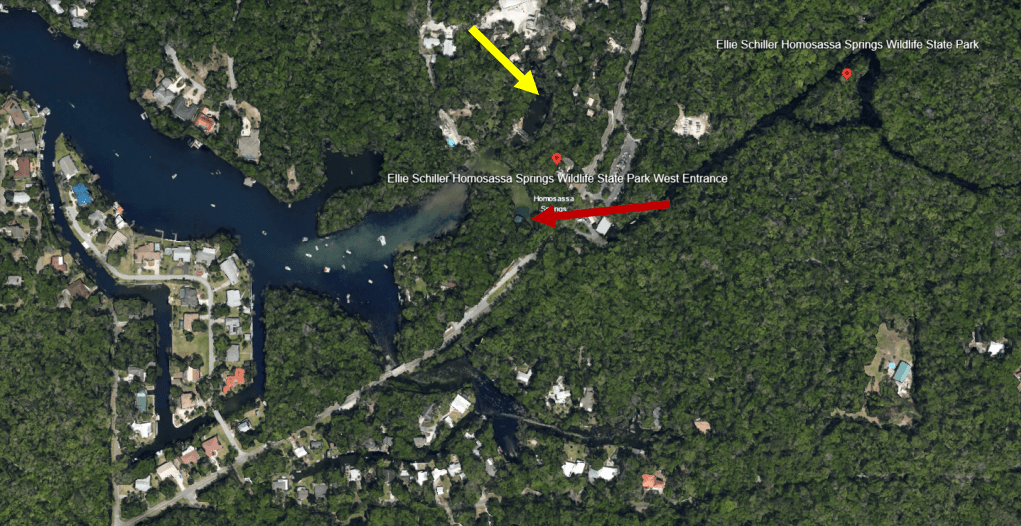

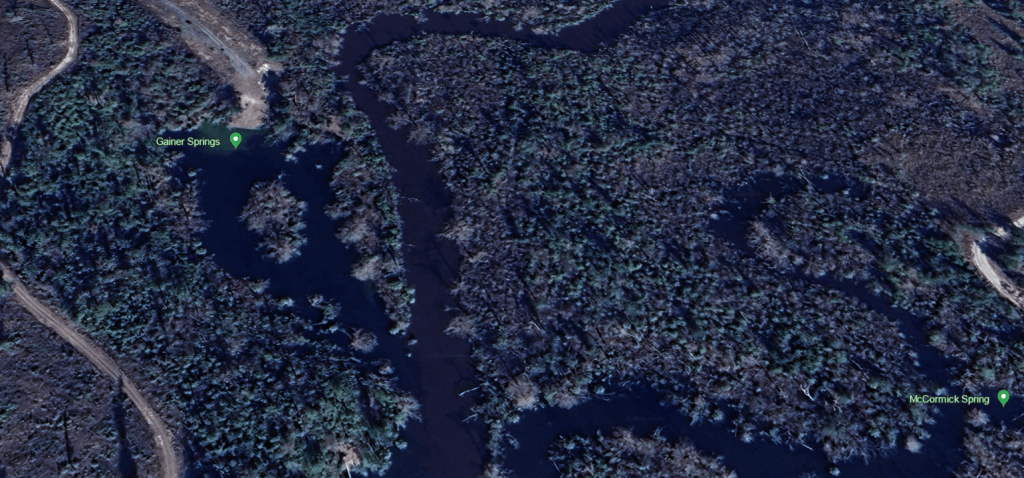

Google Earth images showing the thick development east of Werner-Boyce State Park (top) and a lower altitude view showing Salt Spring (yellow arrow) and Culvert Spring (red arrow).

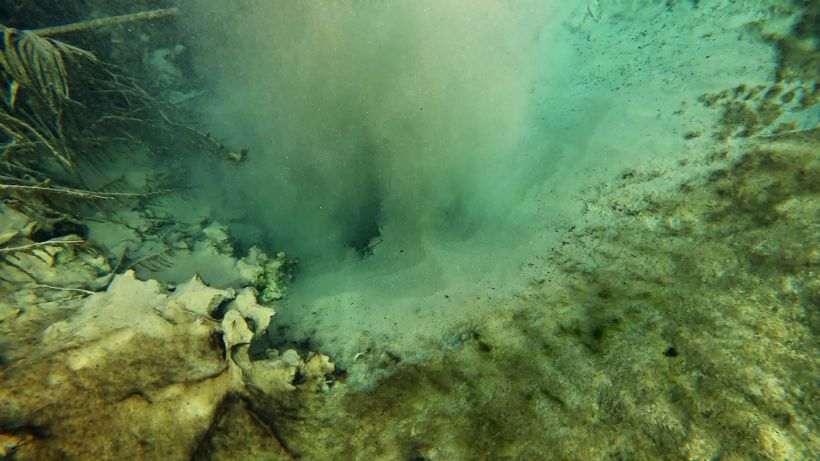

The spring can be reached on foot by a short walk on a trail from the parking lot, but it is only reachable by boat from the kayak launch at high tide. At low tide, a limestone bridge obstructs passage and creates a “tidal waterfall” and spring water flows over and under this bridge. However, the spring also is open to a large pool on the opposite side. According to the park’s unit management plan (https://floridadep.gov/sites/default/files/02.15.2013_WBSSSP_AP.pdf), the vent is in the side of a rock wall in a wide spot of the tidal creek.

The limestone bridge that makes the “tidal waterfall” at low tide.

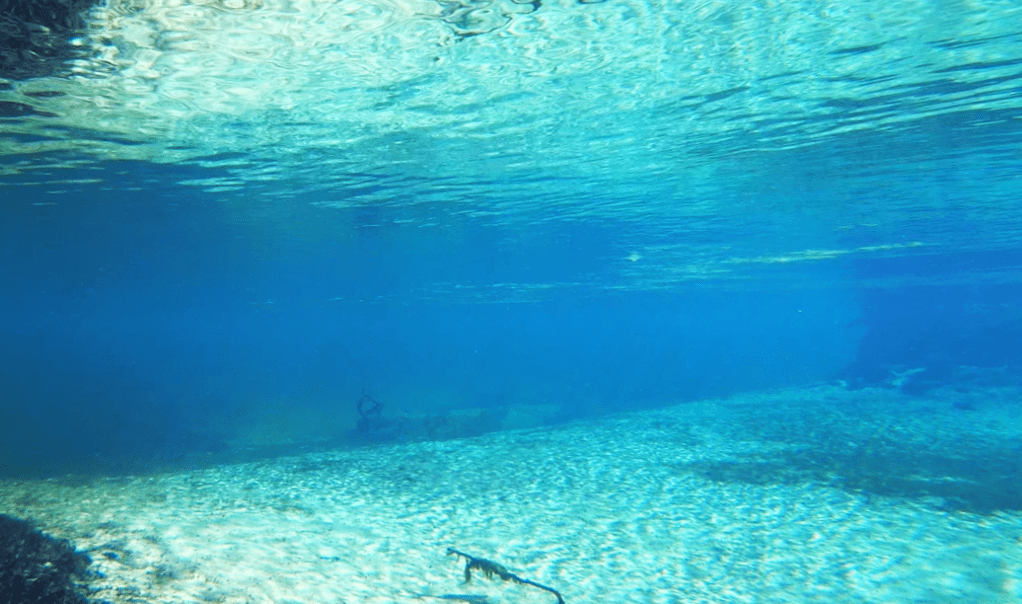

The spring is very deep, with a “200-foot deep solution tube” at its entrance and caverns beyond the tube (https://floridadep.gov/sites/default/files/02.15.2013_WBSSSP_AP.pdf). When I visited, visibility was on the order of centimeters.

The sign announcing to visitors that they have found the spring. Without the sign, the spring would be difficult to find.

At low tide, an alligator watched over the spring, but it was gone by the time that I came back at high tide.

American alligator watching over Salt Spring.

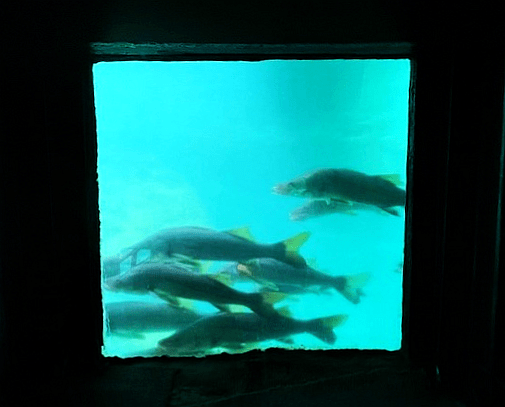

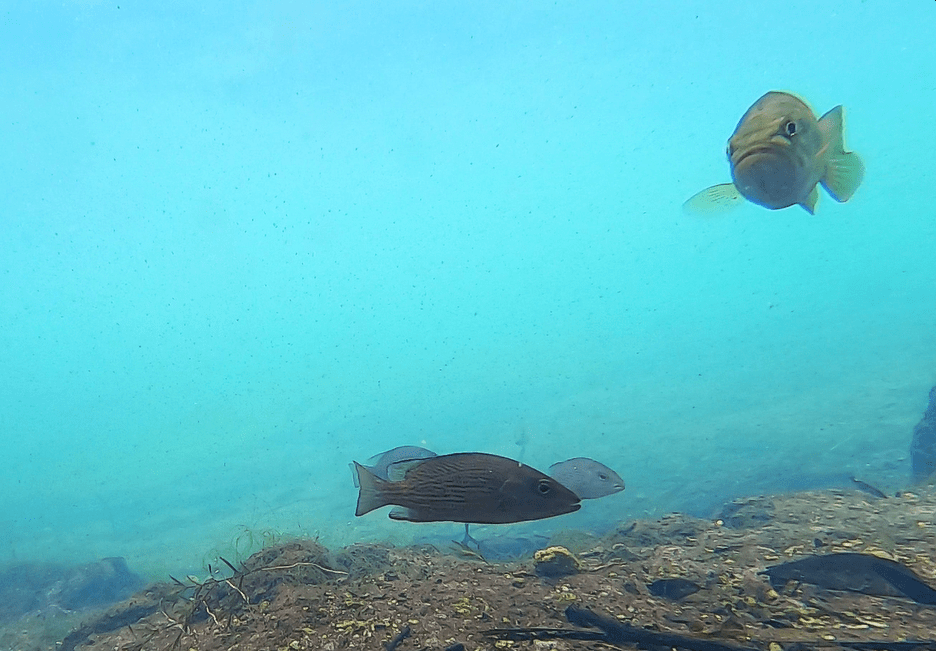

I tried to film at high tide because I could get my boat to the spring with the higher water level, but the water clarity was low and I only recorded a couple of tidewater mojarra (Eucinostomus harengulus).

Tidewater mojarra at high tide in the Salt Spring “run”.

I tried again on foot at low(ish) tide, but alas, the water clarity was still low, as was the fish density. I only was able to see a marsh killifish (Fundulus confluentus) and a couple of sailfin mollies (Poecilia latipinna)

Large, breeding sailfin molly.

There are several other springs in the park, including Cauldron Spring, which walkers cross on the hiking trail to Salt Spring from the parking lot. I apparently missed the origin of Cauldron Spring as it wound back into the salt marsh. From its headspring in a pool (https://floridadep.gov/sites/default/files/02.15.2013_WBSSSP_AP.pdf), it travels north through the culvert under the walking path bridge until it merges with the flow from Salt Spring. I startled a young alligator in this spring and saw a snook (Centropomus unidecimalis) in the run below the culvert late in the day.

Juvenile American alligator in Cauldron Spring below the culvert.

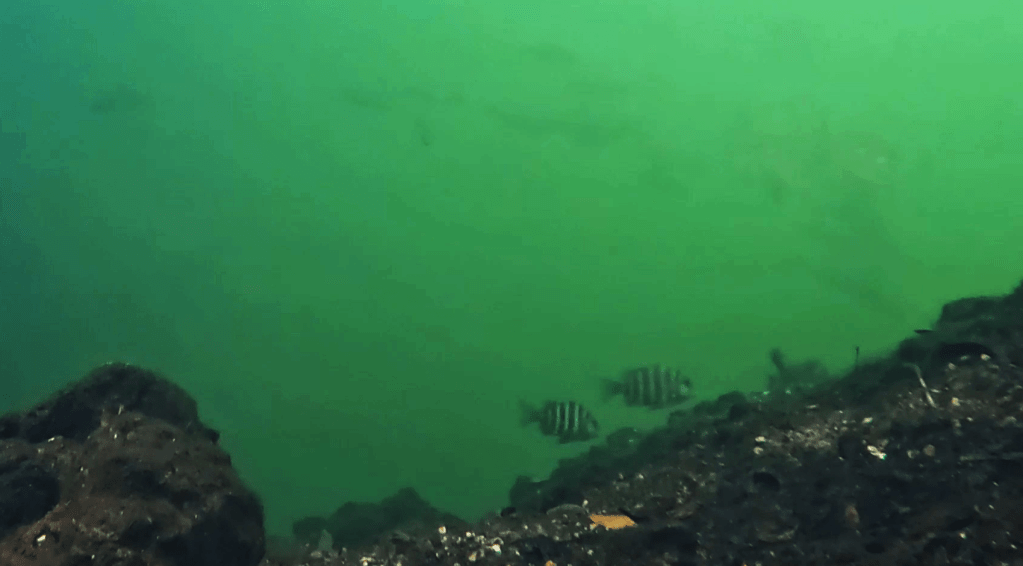

Above the culvert, I recorded more fish in this spring than anywhere else that day, mostly the highly tolerant mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki) and sailfin mollies (Poecilia latipinna), but also a marsh killifish and a couple of spotted sunfish (Lepomis punctatus). However, the water clarity was dreadful everywhere, probably due to natural suspended solids in these salt marsh/mangrove systems.

Marsh killifish in Cauldron Spring above the culvert. Despite the poor water clarity, the fish is identifiable by its stripes and black spot on the rear of its dorsal fin.

The other springs that I saw along the walking path were quite small, including “Reflection Spring” and “Red Spring”. I did not sample these springs.

Red Spring.

Reflection Spring.

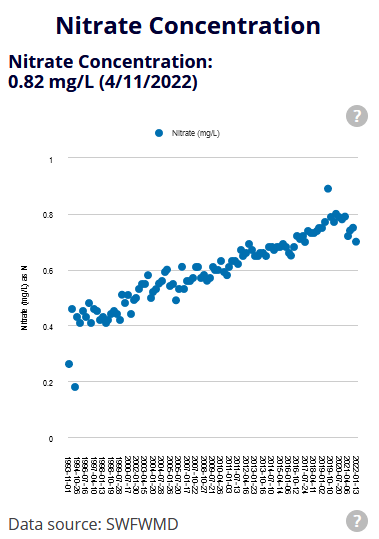

I found almost no data on groundwater flow or water quality for these springs. The park’s unit management plan reported that the flow was 9-10 cfs, as measured three times in the 1960-1970s (I also found a measurement of 8.36 cfs from 1997 on the USGS NWIS website). The report also mentioned that the hydrology of the area was modified by mosquito ditches and by storm water drainage from the town of Port Ritchey just to the south, which occurred both through drainage canals and through sheet flow. Some storm water control pond construction and dredging for residential and commercial areas also has occurred on the lands abutting the park. Although the unit management plan alluded to water quality data, I only found data related to salinity, which I found on the USGS NWIS website. The springs in the park are not in “Springs of Florida” USGS publication (https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00094032/00001/images).

The data that I collected suggested that the groundwater was a bit warmer than the tidal water (25 vs 23oC). The oxygen concentrations were moderate (~4-6 mg/L) and higher above the culvert in Cauldron Spring (7.2-7.5 mg/L). As might be expected, the conductivity (a measure of the number of ions in freshwater, like the freshwater version of salinity) was high in Salt Spring (21-22 microS/cm). It was approximately two orders of magnitude higher than many of the other springs that I have sampled. Interestingly, the conductivity that I measured late in the afternoon in Cauldron Spring was much lower, both below (1.5-1.7 microS/cm) and above (~1.8 microS/cm) the culvert. It would appear that Cauldron Spring is less tidally influenced than Salt Spring, which is connected to the Gulf through channels in the mangroves.