February 2024

At a discharge of 400 million gallons of water per day, Wakulla Springs is one of Florida’s monster spring systems. Its wide headspring drops off quickly to the vent 185 ft below the surface, fed by an extensive cave network that has connections from just south of Tallahassee to the Gulf. Sally Ward Spring enters Wakulla just below the headspring.

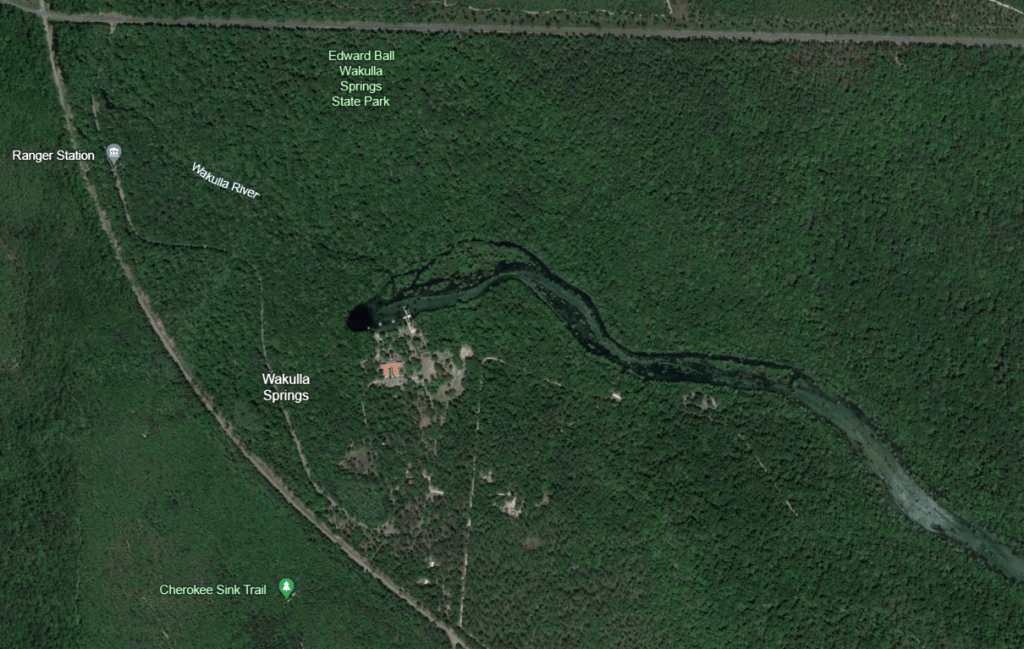

The Wakulla headspring looks like a deep dark hole on the map. The run beyond it is wide and fairly shallow. The water labeled “Wakulla River” on the map is actually Sally Ward Spring.

In some ways, it is one of the best protected springs in the state as well as one of the largest. When he deeded the land to the state, Edward Ball stipulated that the general population would only be allowed beyond the swimming area on escorted tours. He wanted to ensure that the spring would not be loved to death, as they say. As a result, the swimming area with its dive platform, shown in the opening photograph, is the only way that an individual can get on the water without getting a ticket for a pontoon boat ride. Much of the landscape to the east and west of the spring is heavily protected.

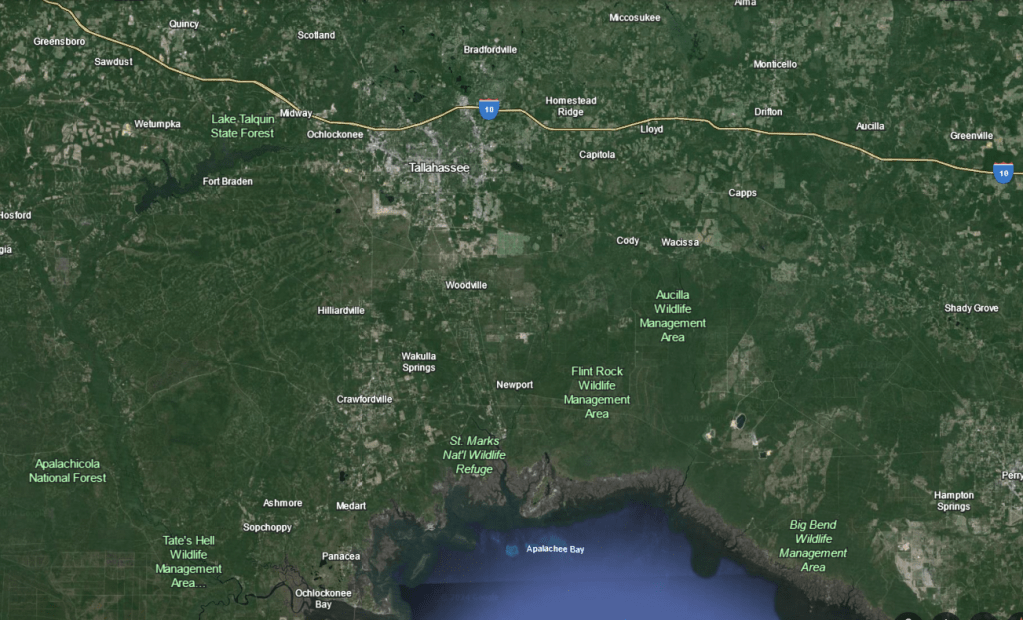

Map of the big bend area of Florida, with Wakulla Springs shown south of Tallahassee.

However, given the extensive connections in the region, the water leaving the vent has likely been impacted at multiple points within its springshed. Landscape impacts are a reality for all Florida springs, but the Wakulla connections are especially vulnerable (an infographic by FusionSparks media is particularly helpful in seeing the flow direction: http://www.fusionspark.com/portfolio/wakulla-springs-interactive-graphic/)

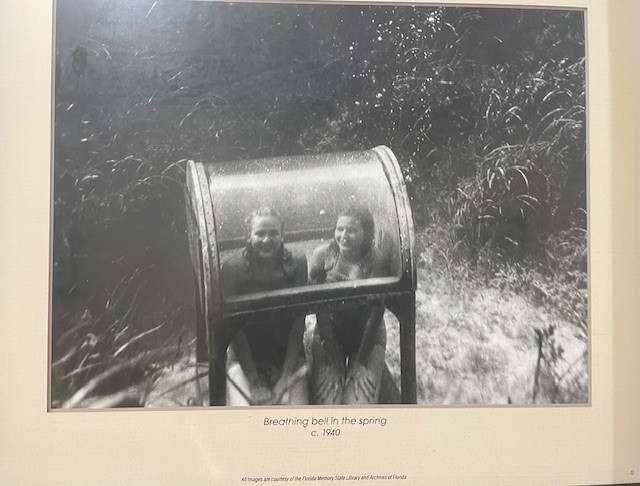

In addition to protecting the spring from heavy human use, Edward Ball also provided the park with a mansion that functions as a lodge and restaurant now. While it has amenities like wifi, history lives on in the lodge.

The entrance to the Lodge.

The lobby of the Lodge with hand painted ceiling beams.

A whole row of historic photos grace the hallway walls.

The Lodge at night, photographed with my back to the spring.

A visit to Wakulla Springs is fun on many levels, but I was there to work. I started on Sally Ward Spring.

Sally Ward Spring

The first Sally Ward vent.

Most people miss Sally Ward Spring. Its runs roughly parallel to the driveway into the park and the access point to the spring is shortly after the entrance to the park off the highway. However, it is difficult to see from the road and there is no obvious parking for it. I must confess that I have not seen the absolute source of all of its water as there is water running from a culvert that runs under the road. However, it seems that most of the water is coming from the two vents below the culvert, and they shimmer with the aqua blue that make so many Florida springs lovely.

The second vent was in a bit of shadow as it was late in the day.

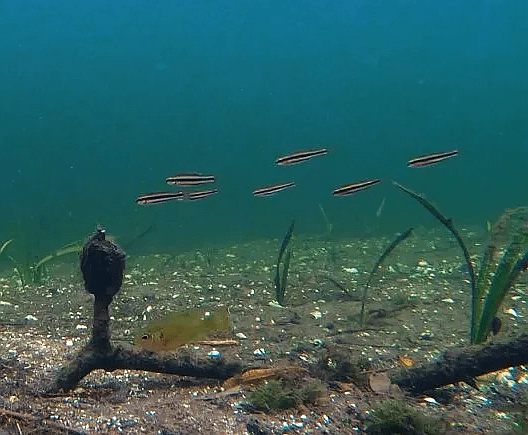

Many of the fish that I observed were mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki), shiners, and sunfish of various species (Lepomis sp.). However, there were more species on the footage than I remembered initially: a fair number of bluefin killifish (Lucania goodei) milling around, some striped mullet (Mugil cephalus) streaming past the camera, a surprising number of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), a golden silverside (Labidesthes vanhyningi), and a couple of turtles.

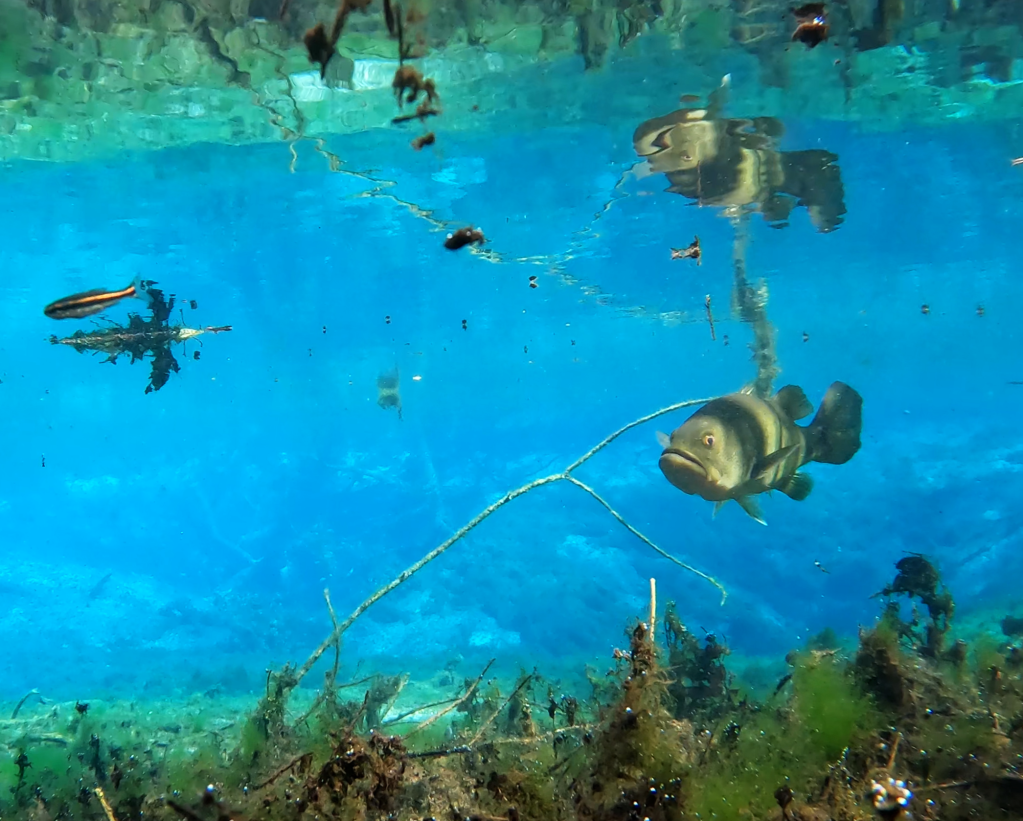

A largemouth bass with a bluefin killifish getting out of its way.

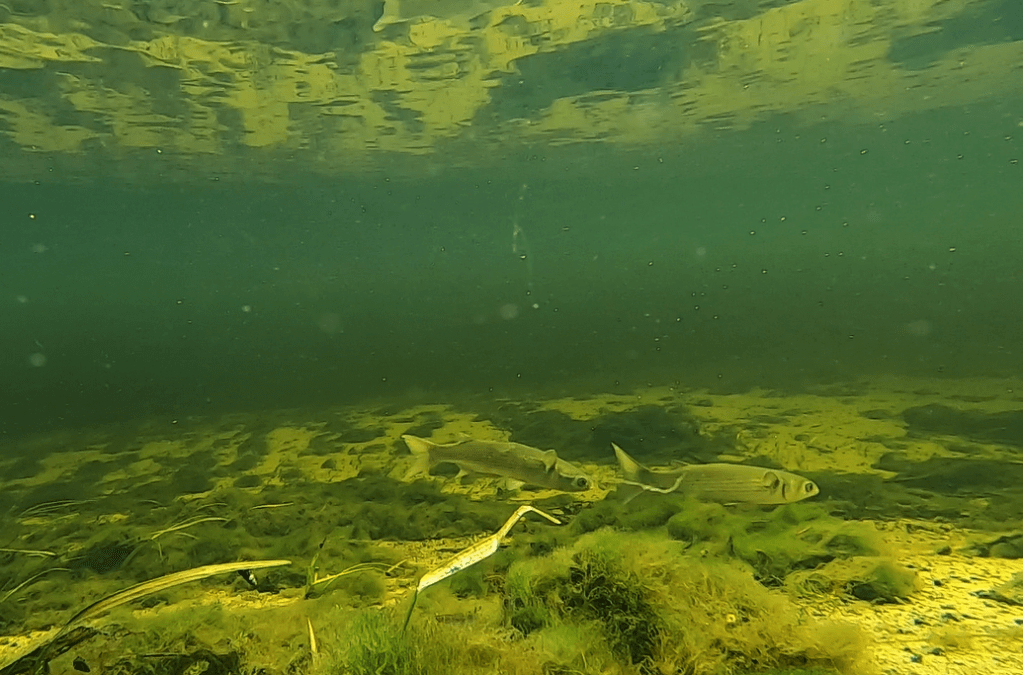

A shoal of mullet.

These small fish originally appeared to be shiners. However, when I zoomed in on the photo, their tails looked square rather than forked, so I think that they are juvenile bluefin killifish narrowly avoiding 10 (!) largemouth bass. I counted a dozen bass on another video downstream.

A golden silverside and a turtle.

I had originally intended to film at 5 locations on Sally Ward Spring (my typical plan). However, there was a large alligator between station 5 and me. I do not usually worry too much about alligators while I am in my boat, but the run was very narrow and I was warned about an alligator at this exact spot in 2017. While looking right at me, it sank down into the water and I decided instead to film where the hiking trail intersects the run downstream. I was rewarded with my favorite video of the entire trip.

The bridge over the Sally Ward run.

Two largemouth bass in Sally Ward run at the bridge.

My favorite: a brown water snake (Nerodia taxispilota), identified by Terry Farrell, foraging on Sally Ward run at the bridge.

Wakulla Spring

Sunrise at Wakulla headspring. Part of the vent was still in shadow.

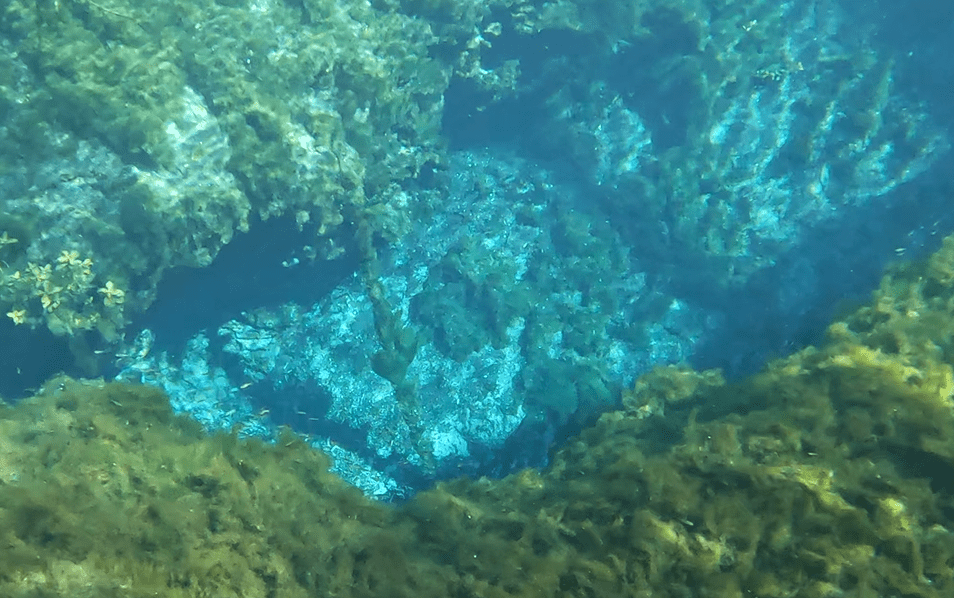

The next morning I sampled Wakulla Spring at 8 am. Wakulla in the early morning is glorious. The massive spring feels almost prehistoric, with its gnarled old cypress trees running in a line down the north side of the run and petrified cypress stumps under the water line.

Some of the ancient cypress trees (top) and a petrified stump under the water in a photo looking back towards the headspring (bottom). The pontoons are the tour and park service boats.

Although the spring was not as clear as I had hoped, the clarity was still good enough to work. The ranger told me that the spring usually clears up after spring break, but the extent of the brown water is new, likely the result of groundwater abstraction upstream in the aquifer (https://news.fsu.edu/news/science-technology/2018/10/24/why-is-wakulla-springs-water-turning-brown-fsu-researchers-may-have-the-answer/). The video below, taken at the headspring, gives an idea of the volume of water expelled and how dark it was this past February. It appears that the darker water was denser than the clearer water, although this effect could have been an artifact of the camera.

Florida gar (Lepisosteus platyrhincus) in the Wakulla headspring.

Some striped mullet munching their way down the spring. It looks like there is a band of darker water above the sediment.

As I worked my way downstream, I was surprised to see a manatee. When I surveyed at Wakulla seven years ago, I saw none.

A manatee friend next to my boat.

Besides the impressively large spring, the gorgeous old cypress trees, the mastodon bones, and the chorus of birds in the morning, one of the notable things about Wakulla Spring is its cohort of beautiful largemouth bass and Florida gar. In addition to the bass and gar, a variety of poeciliids (mosquitofish and sailfin mollies, Poecilia latipinna), killifish, shiners, sunfish, and mullet made the fish assemblage fairly diverse. Turtles were abundant, too.

Largemouth bass.

Some lovely redbreast sunfish (Lepomis auritus).

A big seminole killifish (Fundulus seminolis) and a couple of spotted sunfish (Lepomis punctatus).

More striped mullet.

A turtle at the confluence of Sally Ward and Wakulla Springs.

As I worked my way down the run and up the side channel, I was passed by the park service staff escorting a couple of scientists, one an older gentleman. I am not sure who he was, but he asked me if I was filming the little fish. He said that bluefin killifish disappeared from the spring for a while. Happily, I filmed a lots of them.

Bluefin killifish and a redear sunfish (Lepomis microlophus).

My only disappointment was that I failed to get on video the baby alligators that I scared (by accident) from a nest or the older (but still small) alligator from the bank. All I got was the trail.

The trail of a startled alligator.

Because I was trying to look for saltwater influences on spring fish assemblages, I decided to try filming downstream at the State Road 30 bridge. Although I saw a crab and a couple of sunfish, most of the animals that I observed were olive nerites (Vitta usnea), which represent a brackish species that occurs in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

This video of olive nerites crawling is sped up 3000x. A small bass zooms through the video if you can catch sight of it.

With the exception of the tannin stained water coming out of the vent, the water quality of Wakulla Spring appears to be generally fairly good. The likely culprit for the increase in tannin-stained water coming out of the vent, according to FSU scientists, is higher groundwater withdrawals to support growing populations in the region. Tannins are produced naturally when plant material decomposes in swampy conditions, much like steeping tea. The tannin-stained water then enters the aquifer in the regional forests naturally. However, prior to increases in groundwater withdrawals, there was enough clear water in the system that this tannic water was diluted or flowed elsewhere.

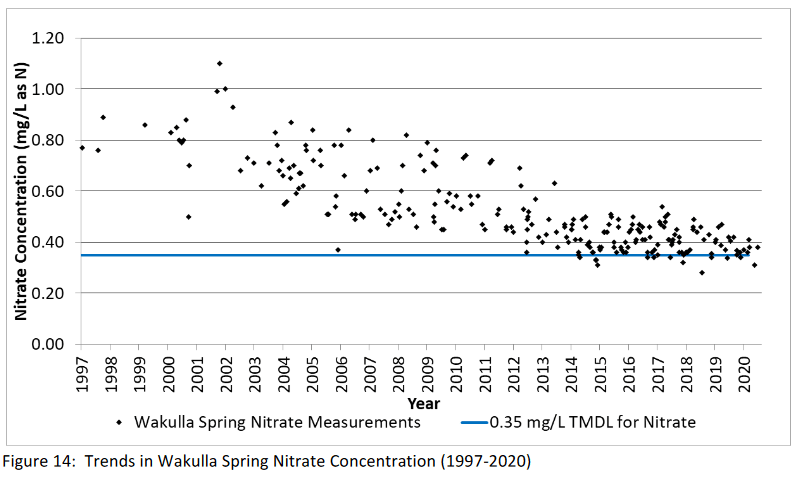

With respect to nutrients, the spring has undergone several studies and the history of this work is outlined in the spring’s MFL plan (minimum flow and level). One such study, in 2004-2005, suggested that the city of Tallahassee’s water treatment facility was contributing a great deal of nitrate to the spring due to leakage through the underground connections in the limestone. The water treatment facility was upgraded in 2012. Later, BMAP (basin management action plan) and MFL programs were developed for the spring in 2018 and 2021, respectively. The BMAP, which was primarily focused on nutrient abatement for the spring, again identified Tallahassee’s water reclamation facility as the largest contributor to nitrate concentrations in the spring. As a result, the facility was upgraded again, this time to “advanced wastewater treatment”. The MFL document, which was primarily focused on water quantity but also included water quality and ecological data, reported that by 2021 septic tanks were the largest contributor of nutrients (34%), followed by atmospheric deposition (27%), and farming (21%). As a result, Leon County aggressively constructed four major septic-to-sewer projects, which put homeowners on sewer rather than septic, between 2019-2021. Since the late 1990s, the nitrate concentrations appear to have dropped by almost half. It appears that the biggest improvement was from that 2012 upgrade, but that the other two programs, initiated by the BMAP and the MFL, have continued the nitrate concentration decline towards the 0.35 mg/L baseline goal.

Figure from: Recommended Minimum Flows for Wakulla and Sally Ward Springs, Wakulla County, Florida, Northwest Florida Water Management District.

The conductivity (freshwater version of salinity) of Wakulla and Sally Ward springs has tended to be moderately low for Florida springs (~300+ microS/cm). My measurements agreed with this trend (308-346 microS/cm) in the two springs and the conductivity was only slightly higher in the Wakulla River at the State Road 30 bridge (334-380 microS/cm). Similarly, the dissolved oxygen has tended to be fairly low in Wakulla Spring (1-3 mg/L). The dissolved oxygen that I measured was fairly low at the Wakulla vent (2.0 mg/L) and in the vicinity of the Sally Ward vents (3.0 mg/L). However, the oxygen downstream of the Wakulla headspring was a bit higher (3.3-6.6 mg/L), as it was in Sally Ward (3.9-8.4 mg/L), likely due to the large eelgrass (Valisneria americana) and algae beds.

I think I did a dive in Sally Ward Spring, about 20 years ago. The most memorable part of that dive being the drive back to the main road, on a very slippery, muddy road as the skies were opening up.

LikeLike