February, 2024

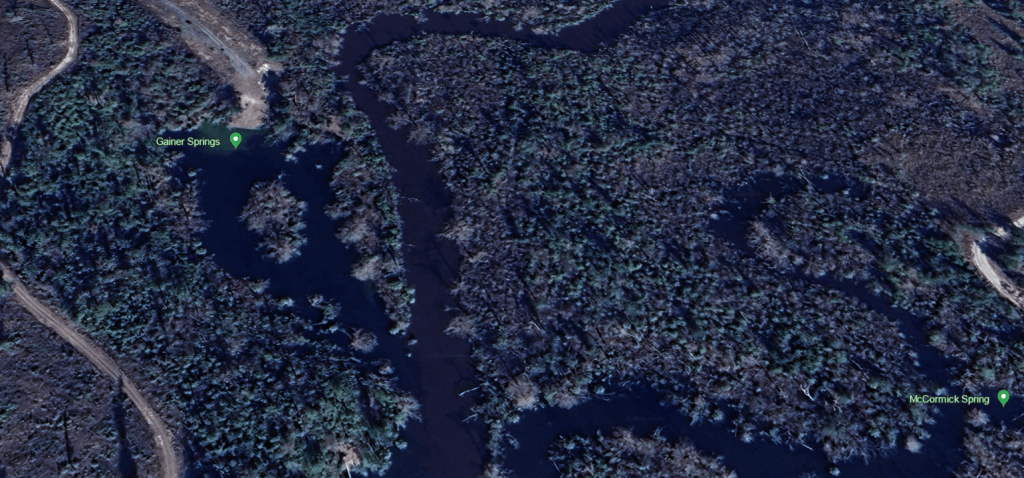

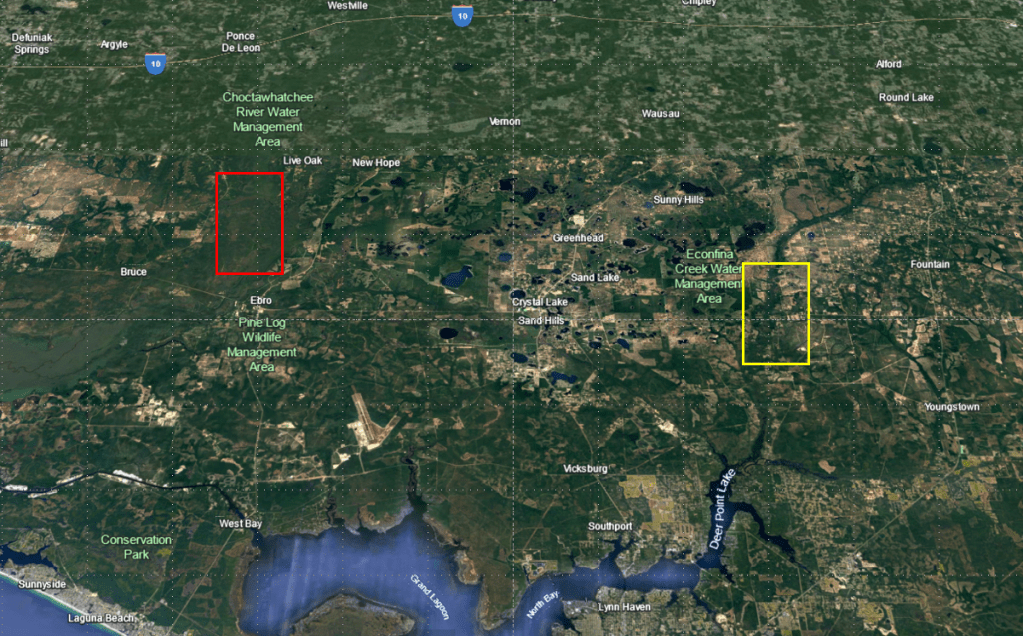

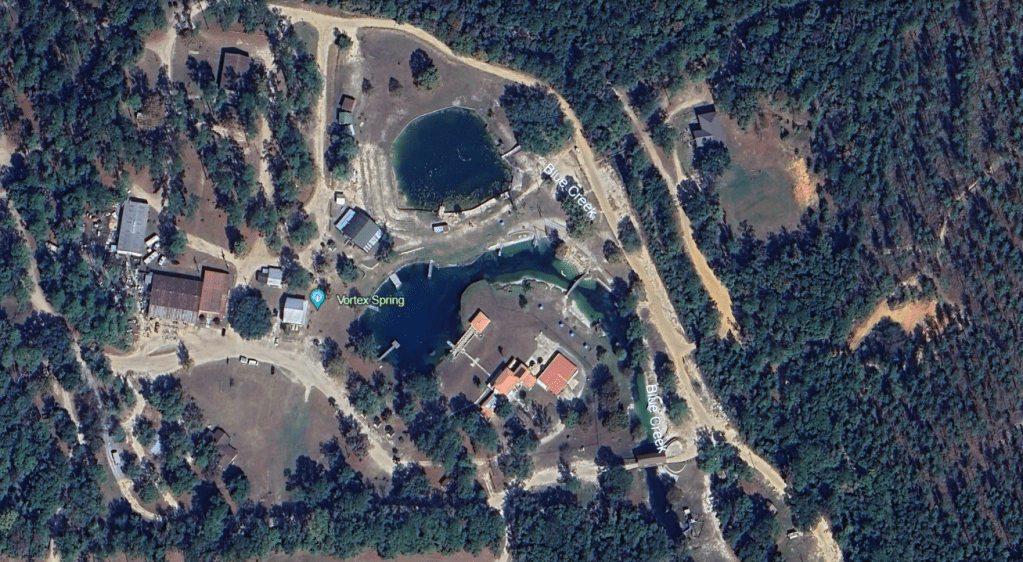

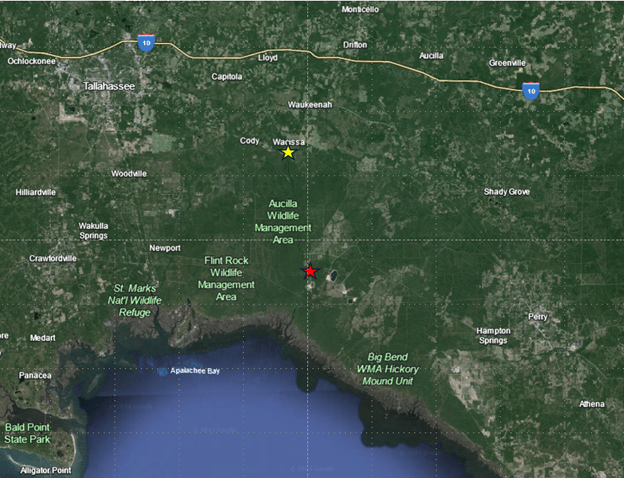

Pitt (above), Sylvan, and Williford springs are just upstream of the Gainer springs group on Econfina Creek. The region around Pitt and Sylvan Recreation Area hosts a cluster of springs that contribute to Econfina Creek, which flows into Deerpoint Lake and eventually St. Andrews Bay at Panama City. The region is agricultural to the east, water management area to the west, and a mixture of both upstream.

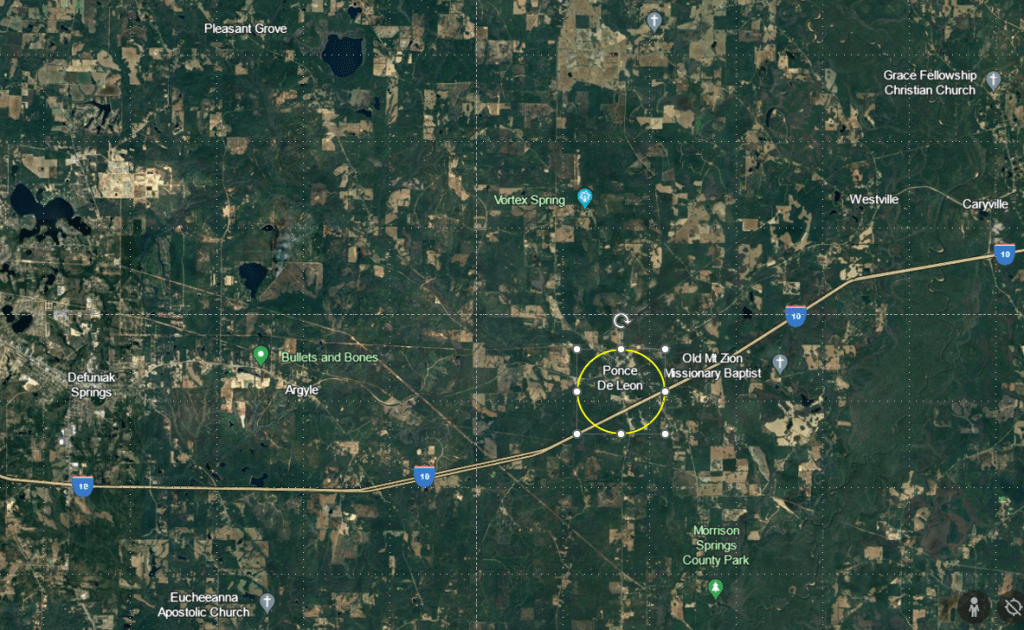

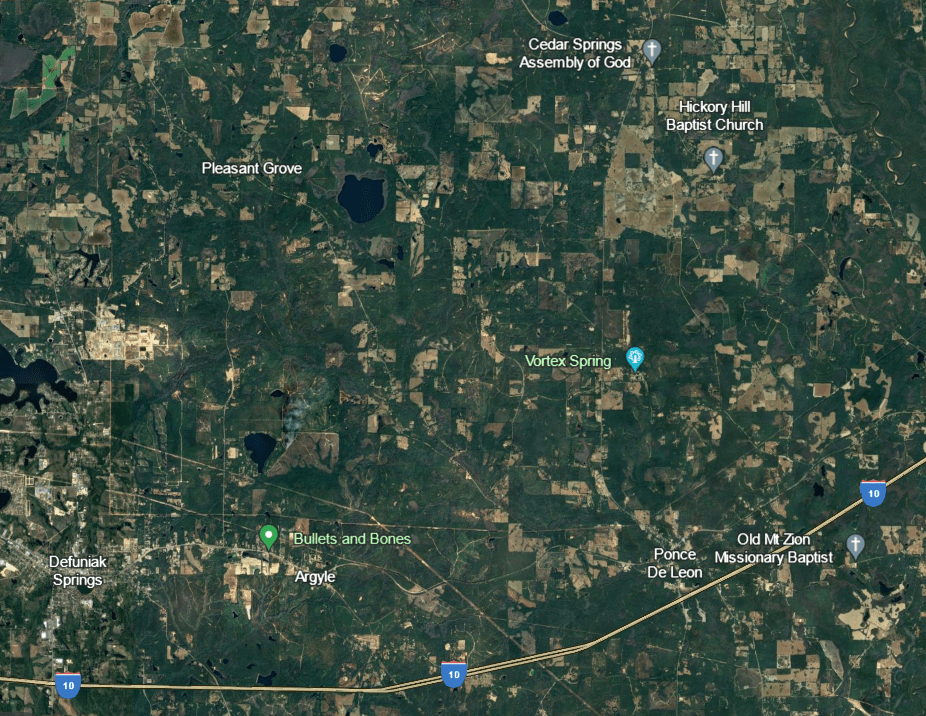

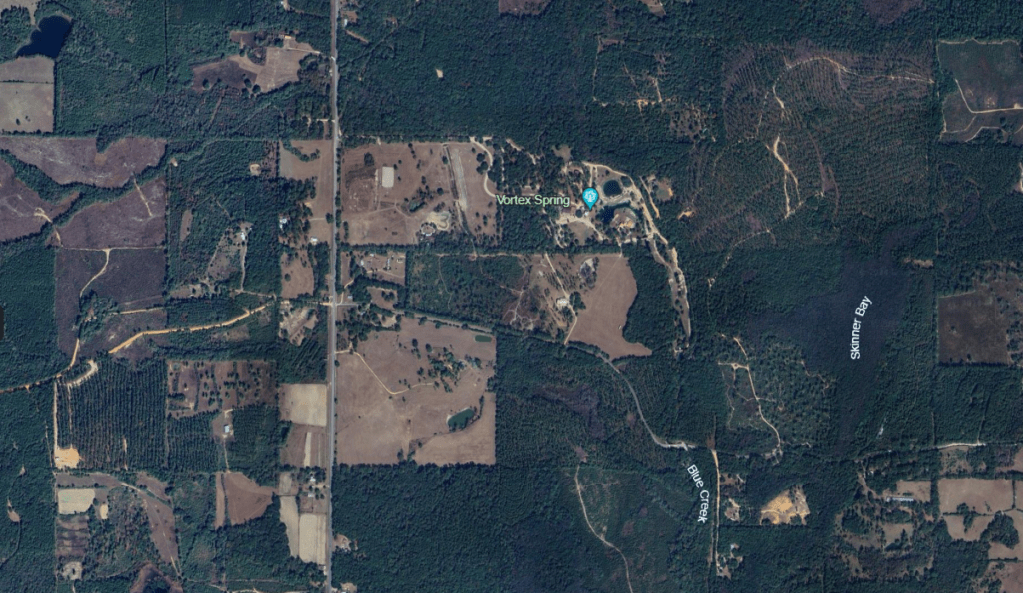

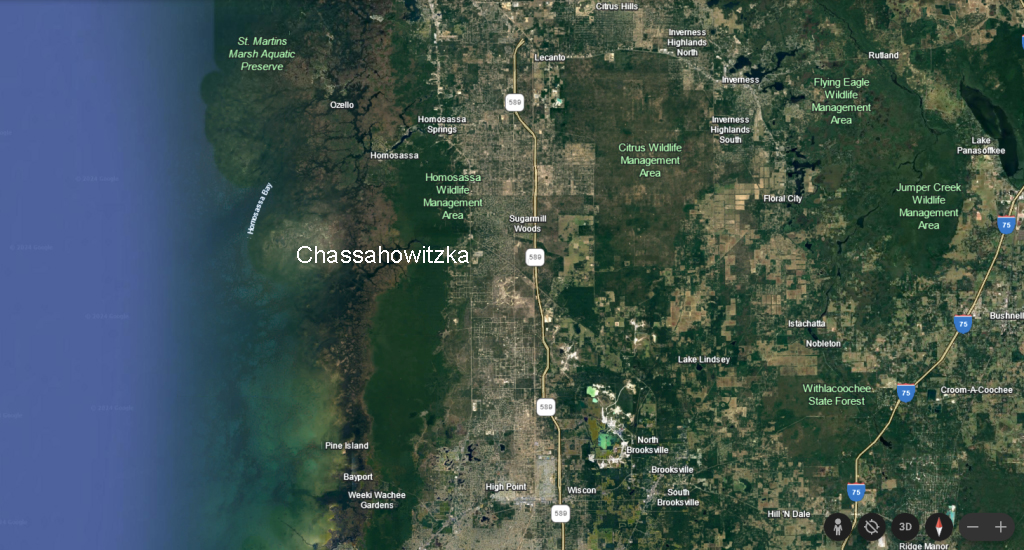

Map of the landscape around Pitt, Sylvan, and Williford springs (top) with a closer version showing some of the many springs in the vicinity (bottom).

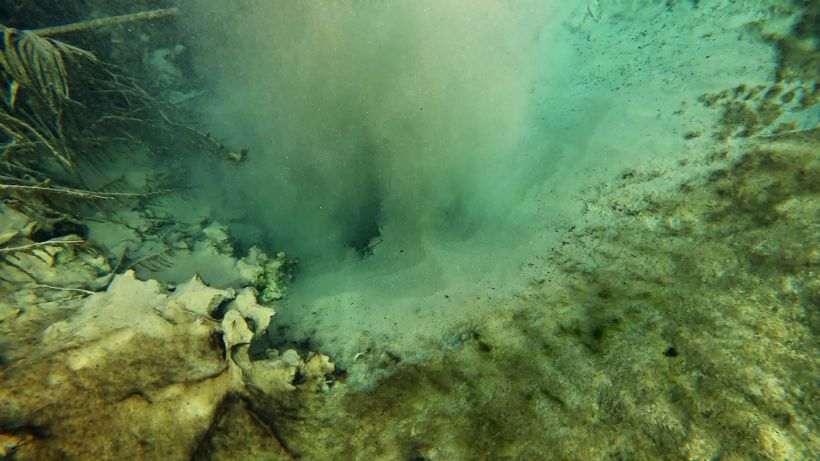

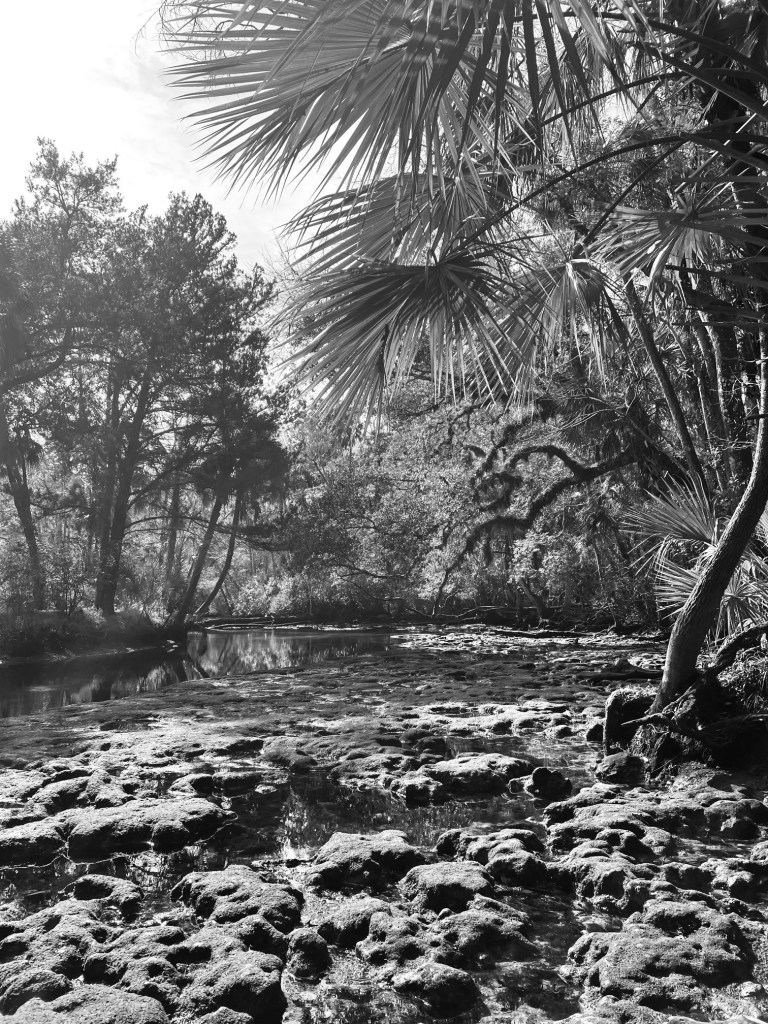

Pitt Spring has a parking area adjacent to it, but walking trails connect with the other two spring systems. I raced to visit these springs before I ran out of light for the day. Because I had to use a boat to get there, I visited the Sylvan Spring system first. In my haste, I only found the spring system by the clear water flowing out into the flooding Econfina River. I paddled up the short run to a flat, sandy underwater plain that was largely covered with dead algae. Near the bank at the end of this plain, I saw a tell-tail sign of spring vents: circular rippling on the surface.

The three Sylvan vents at the surface.

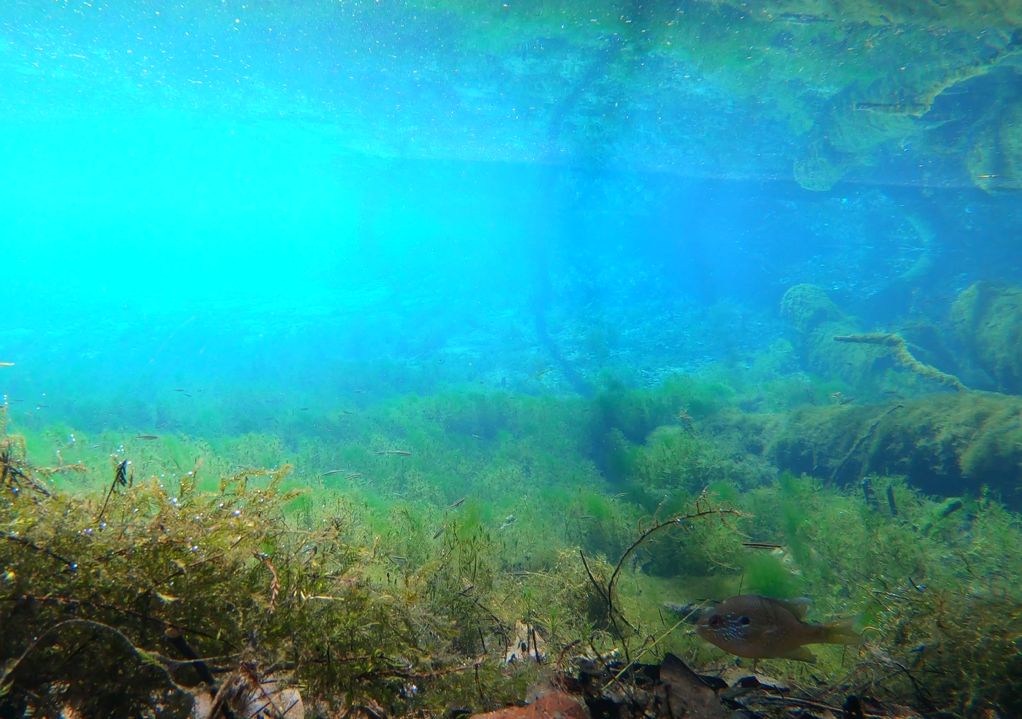

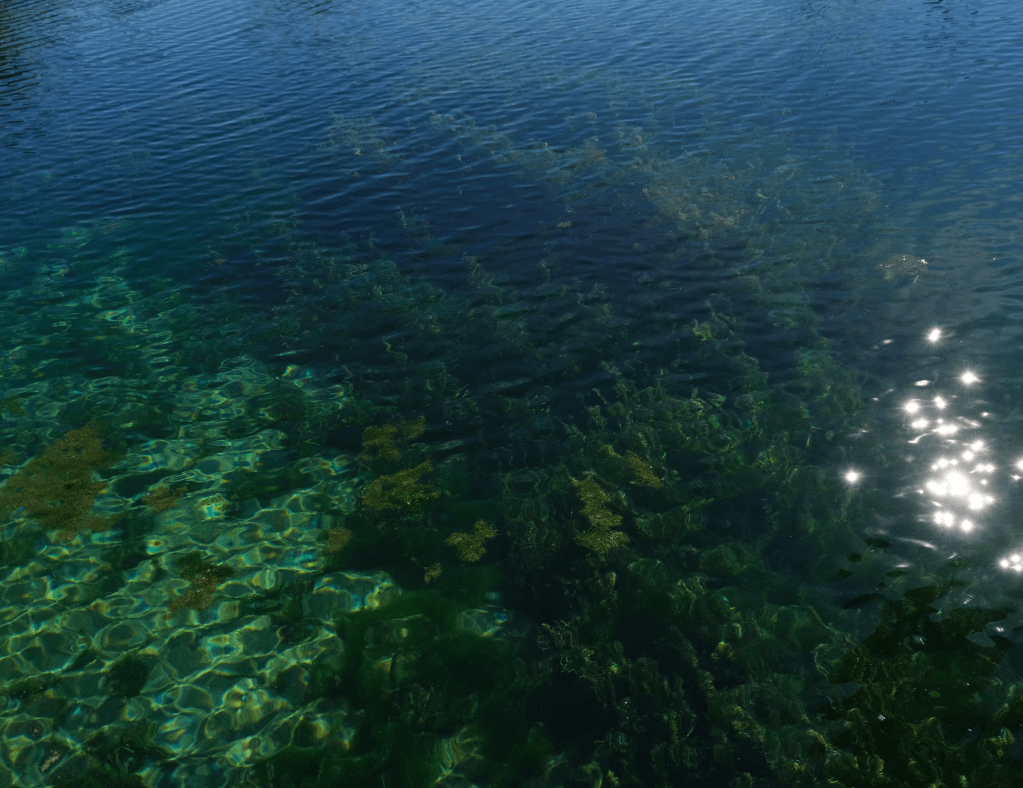

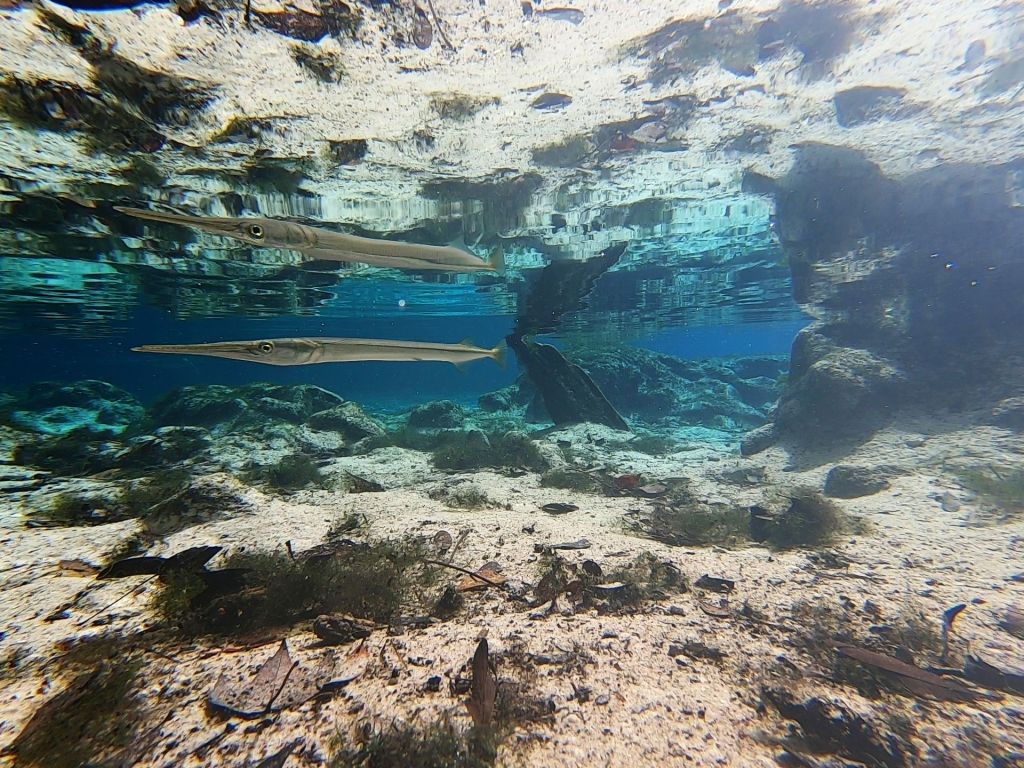

Underwater, the vents were obvious by the live, bright green algae waving in the flow.

Sylvan Spring vents underwater. Notice the fluttering green algae.

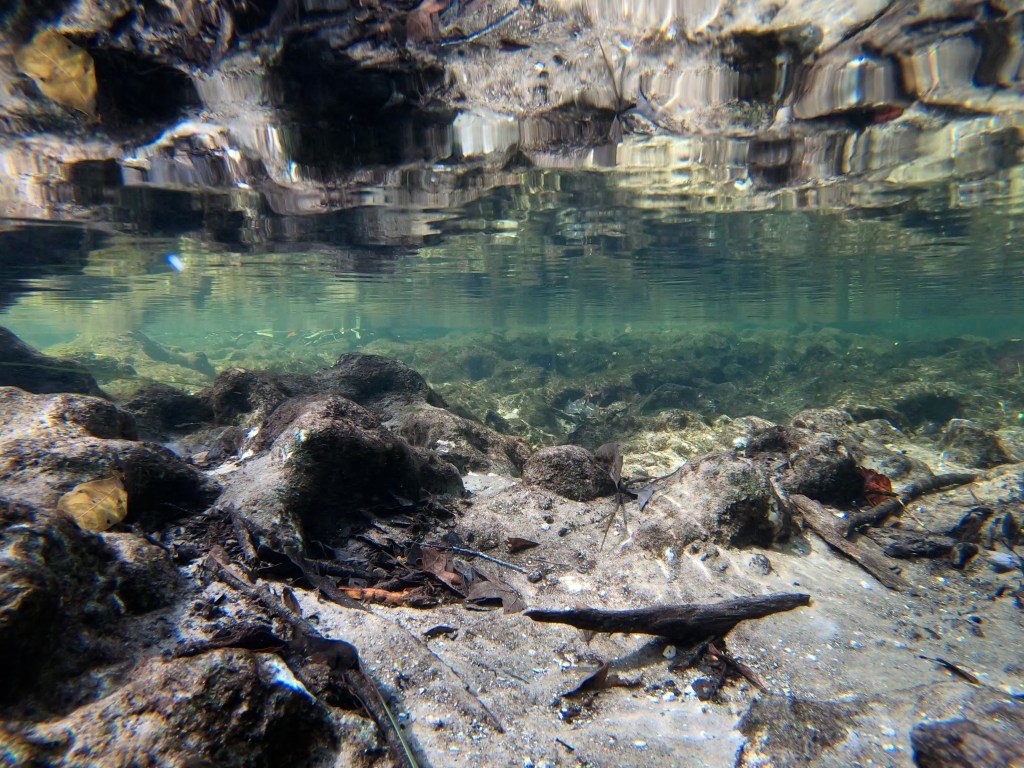

The dead algae-covered sand plain near the Sylvan vents.

The fish density was quite low in this spring system and virtually all of the fish that I observed were sunfish of one species or another. I only observed larger numbers of fish, interestingly, at a spot where the water was murky with suspended material. Here, the bluegills were undoubtedly eating invertebrates from the decaying algae.

A spotted (Lepomis punctatus) and a longear sunfish (Lepomis megalotis) in clear water and bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus) in the murkier water.

Near the confluence, there were lots of snails covering fallen log, although I sadly did not pick any up to identify them. Next time.

Snails dotted all over a fallen log with a lone sunfish in the background.

The river was running fast due to the flooding and I flew back to the canoe launch.

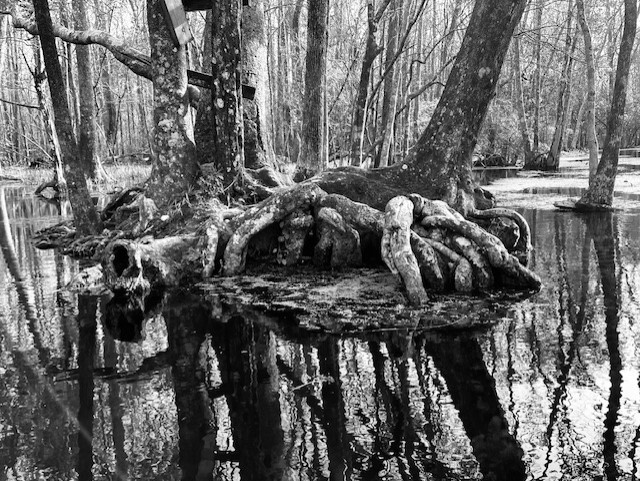

Floating down the Econfina River to the canoe launch from Sylvan Spring.

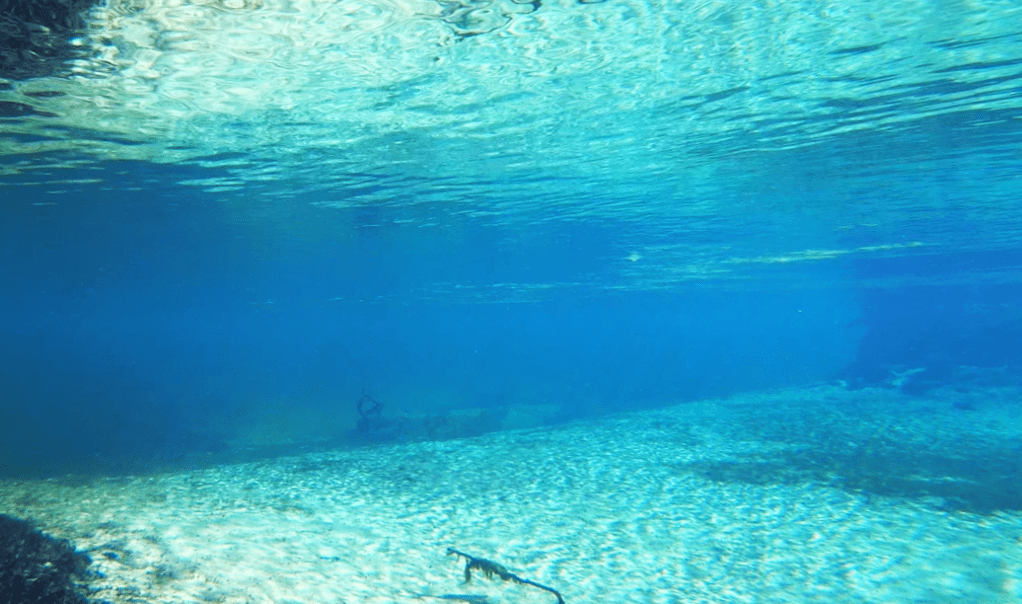

Once I pulled the boat out of the water, I visited Pitt Spring on foot as the confluence with the river was blocked. Pitt Spring was a contrast to the Sylvan system: lovely, clear and blue, with a large, round vent and almost no run. However, the fish diversity was low there as well. I thought that there were only shiners and sunfish, mostly bluegills (Lepomis macrochirus), but when I scanned through the extra footage, I discovered a fish new to me: a lovely little russetfin topminnow (Fundulus escambiae).

Shiners (top), bluegill (middle), and a russetfin topminnow (bottom) at the Pitt headspring.

After filming at Pitt Spring, I hurried up to Williford Spring by car. A trail leads to the spring from the Pitt/Sylvan parking lot, but I was running out of daylight. Had I had more time, I could have paddled up to it, but it was a bit of a trek, so I filmed on foot only.

The Williford Spring vent at sunset.

The fish density in Williford Spring also was low. I only observed mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki) and a few bluefish killifish (Lucania parva). I was rewarded, however, with a tiny juvenile musk turtle in one of the videos. I have seen an adult musk turtle (Sternotherus sp.) mistaken for a juvenile snapping turtle because they are so small; the juvenile musk turtle is barely bigger than a quarter.

Underwater views on either side of the Williford vent, with mosquitofish at the surface and a tiny juvenile musk turtle in the lower left hand corner of the bottom photo.

All three of these springs benefited from restoration projects between 2012 and 2015. Projects included bank stabilization and stormwater runoff reduction. I could not find specific water quality information for the springs, but nutrient concentrations for Econfina Creek have been generally low for the period of 2009-2020 (https://protectingfloridatogether.gov/water-quality-status-dashboard). Most data points have been in the ~0.2 mg/L range with periodic measurements up to 0.6 mg/L and a few high spikes up to 1.4+ mg/L (that would be considered quite high) during the period of the restoration. Phosphorus has exhibited similar trends with most points quite low (~0.01 mg/L), virtually all points below 0.03 mg/L and just a few points in the 0.035-0.045 mg/L range. My oxygen measurements were low for the headspring of each system (0.45-1.95 mg/L) and the measurements for the Sylvan run only reached as high as 4.72 mg/L for one sample. The conductivity was low 1330-1400 microS/cm for all samples.