I gravitate toward small, sandy spring runs with overarching tree canopy, so Juniper Spring has always been a favorite. Like many, or perhaps most, of the big springs in Florida, the Juniper headspring was modified long ago for swimming.

The Juniper headspring. The vent is in the foreground of the photo.

The modification makes for a nice, easy-access swimming area, but once the run leaves the headspring area, it is unmodified and seemingly pristine. The bottom is sandy and the water is shallow and so clear so that it almost looks more like a dry sand path rather than a spring run.

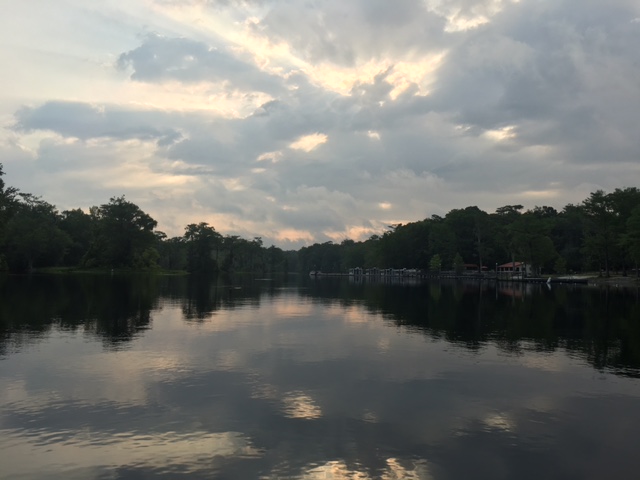

The Juniper Spring run just below the put-in for canoes.

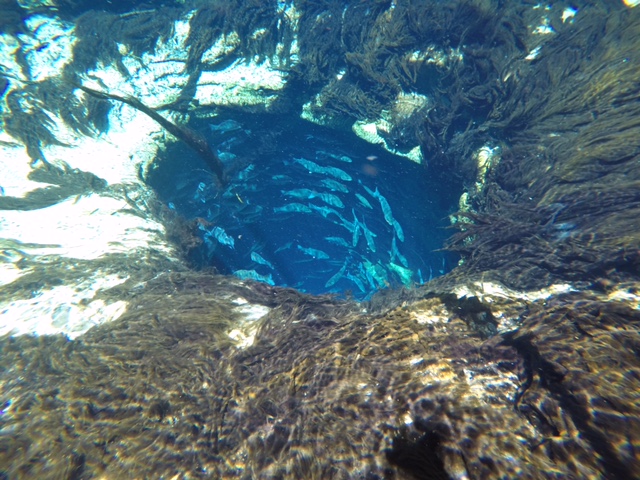

Looking upstream under water at the put-in spot for canoes.

Views of the upper run of Juniper Spring.

One of the things that I love about Juniper Spring is that it has loads of blackbanded darters (Percina nigrofasciata) in the upper part of the run. I can watch them doing their darter business, planting themselves on the sand until they decide it’s time to move, then lifting up and floating downstream until they turn around and plant themselves again.

Blackbanded darters and shiners (Notropis sp.) working the flow just downstream from the put-in spot for the canoes in the upper reaches of the spring run. In the video two darters inch their way up the run in the lower left quadrant. Some other darters work their way across the run further back in the video. They look like they are expending next to no energy to stay in place as they plant their pectoral fins in the sand. By contrast the shiners are working hard with their tails to stay in the flow.

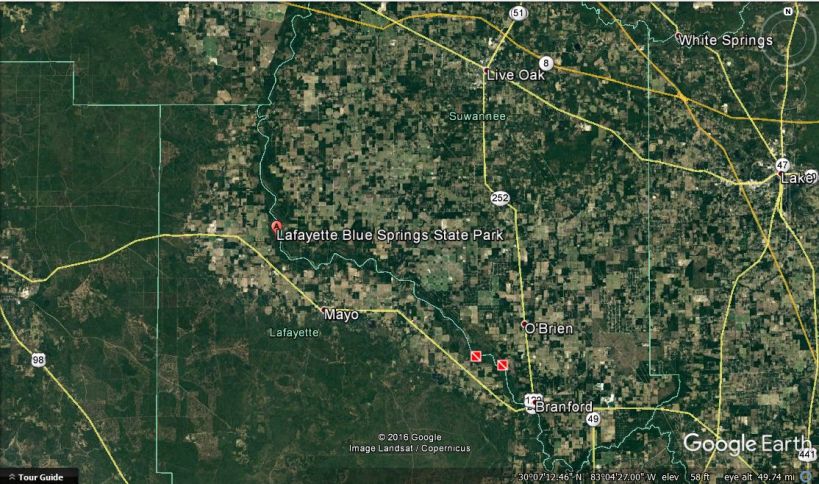

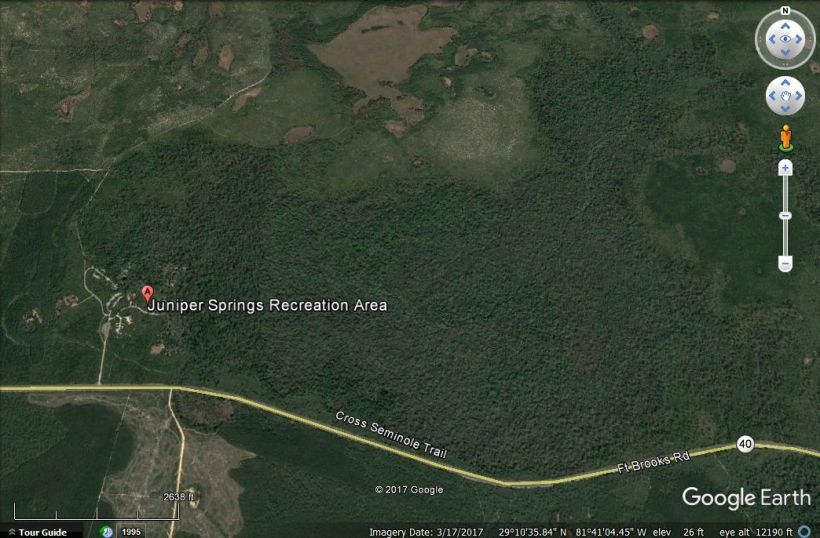

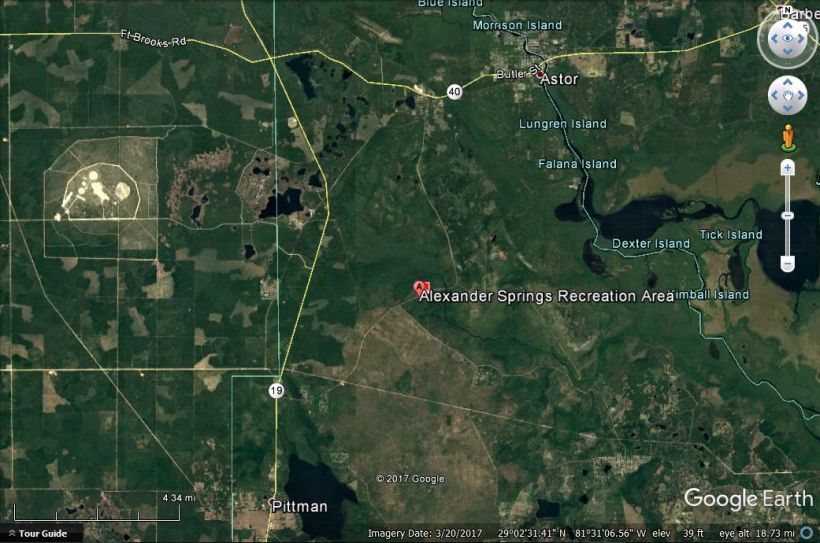

Like the other Ocala NF springs, the landscape around Juniper Spring is conservation land. The spring run is so narrow that it is hard to see even on a closeup aerial shot.

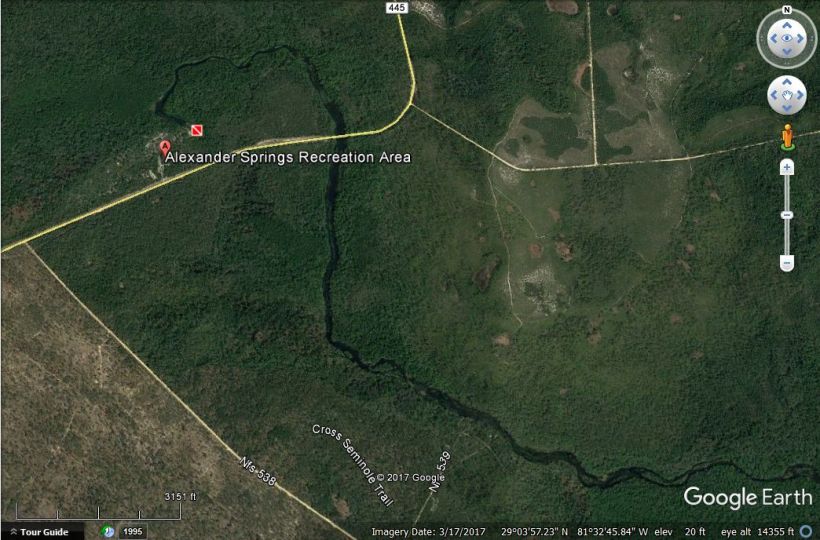

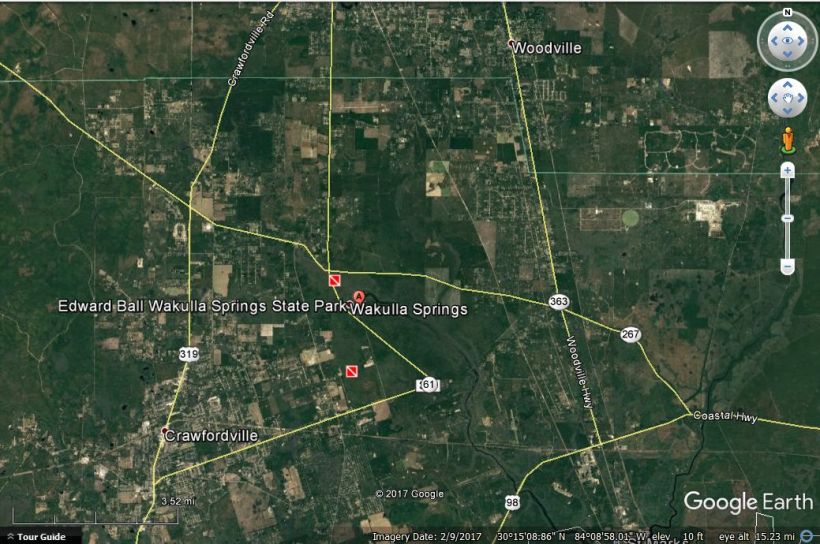

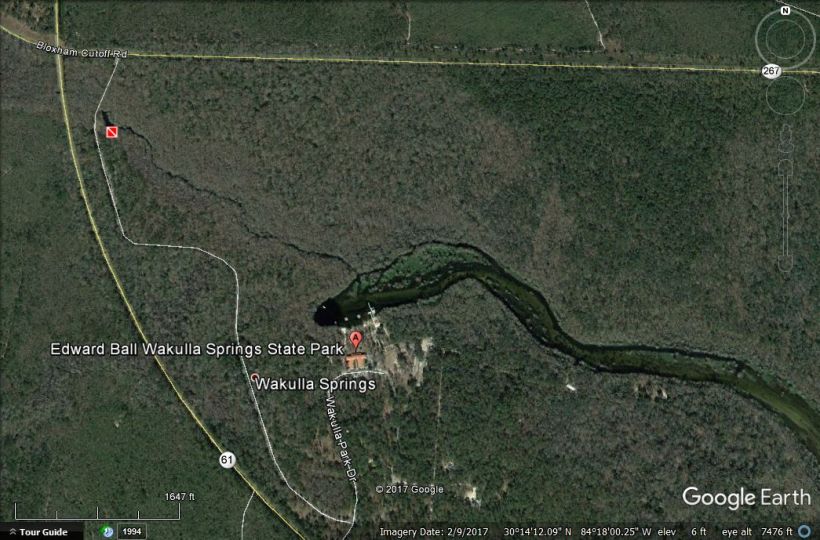

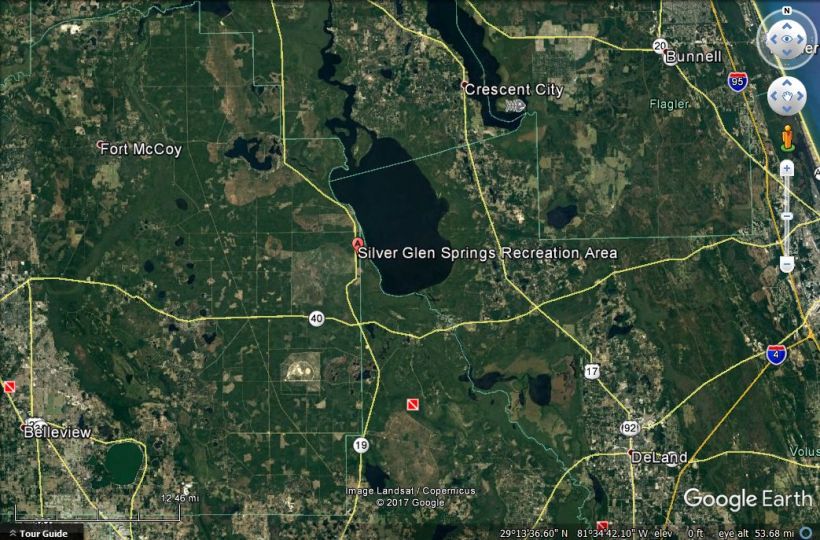

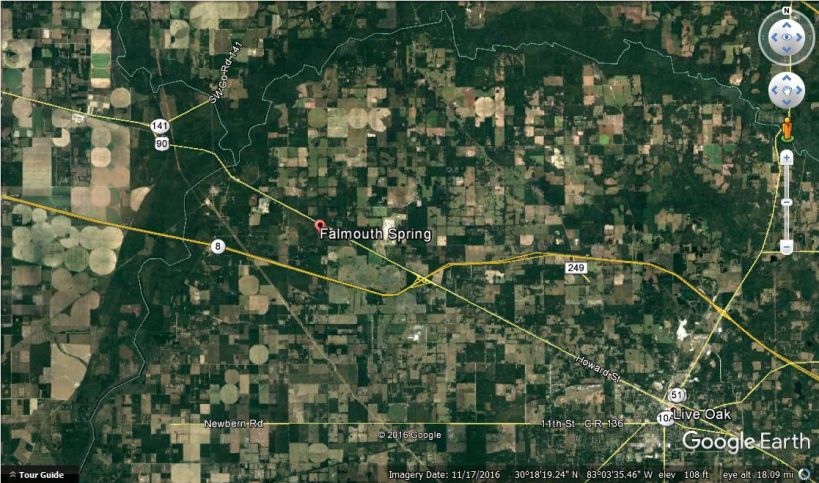

Google Earth image of the landscape around Juniper Springs.

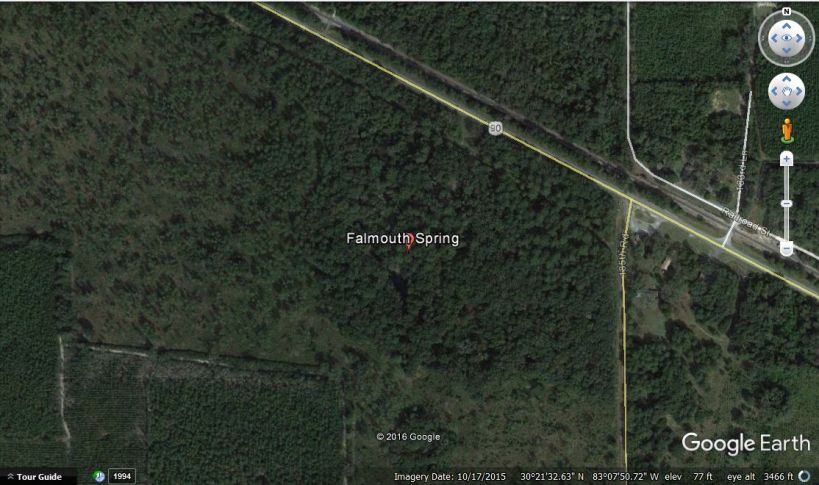

Closeup of the Juniper Springs landscape; the spring is barely visible in the upper right quadrant of the photo although it starts on the left side. It is interesting how the tree cover appears much thicker around the spring run.

The discharge and conductivity of Juniper Spring are quite low compared to the other Ocala NF springs (dishcarge = 11 vs. 1070-5800 cfs, conductivity = 125 vs. 1070-5800 micromhos/cm). The spring is a little colder (22oC vs. 24oC) and more oxygen-rich (7.6 vs. 2.8-6.2 m/L) than the other springs as well. Although the high dissolved oxygen concentration is likely a function of the low surface to volume ratio (more of the water exposed to air) and the lack of large volumes of organic matter (bacteria breaking down organic matter use oxygen), oxygen dissolves more readily in colder water as well.

Downstream, quite a long way, the spring widens and deepens slightly.

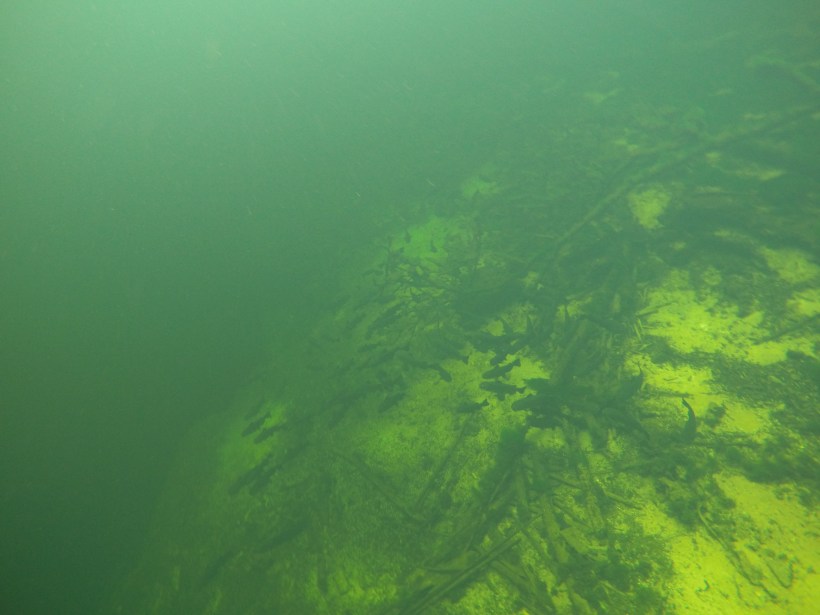

The water clarity in this area of the run is a bit lower, as is the flow. The fish assemblage changes as well.

Shiners (Notropis harperi?) in the deeper and wider area of the run downstream.

Even further downstream, the overhead canopy disappears and the run acquires some deep-ish pools.

Views of Juniper Spring run. I believe that the last photo was taken shortly before the “rapids”. The rapids are tiny as rapids go, but still fun.

Even further downstream just past the pull-out point for canoes, eelgrass (Vallisneria americana) or Sagittaria takes over the bottom of the run. However, I did not catch many fish on video down here.

Eelgrass or Sagittaria below the canoe exit for the shuttle.

It would be interesting to paddle the whole run and get a picture of the fish assemblage further downstream!

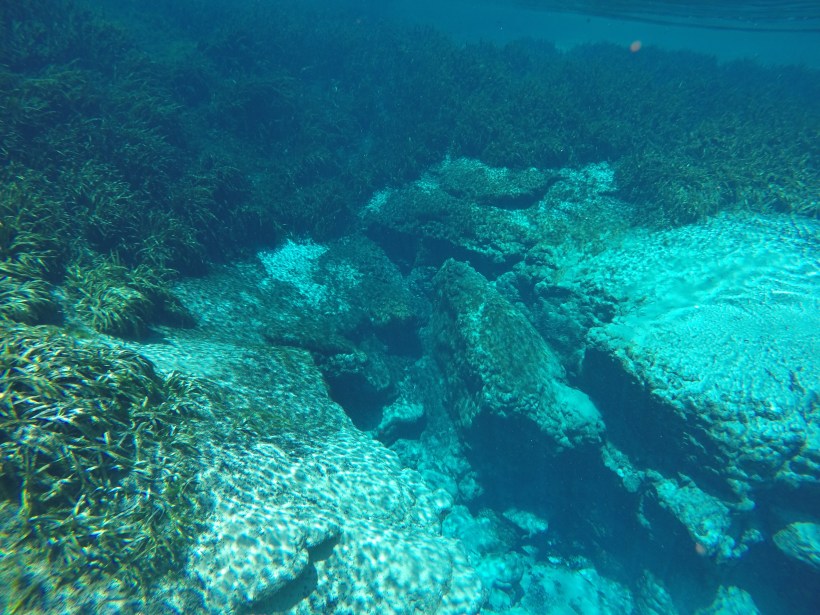

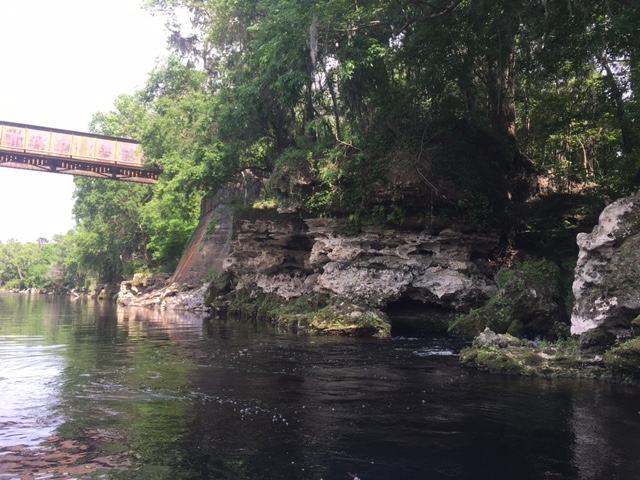

A close-up of the limestone that makes up the bridge. Limestone is a very soft rock that erodes relatively easily in even very slightly acidic water.

A close-up of the limestone that makes up the bridge. Limestone is a very soft rock that erodes relatively easily in even very slightly acidic water.